Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

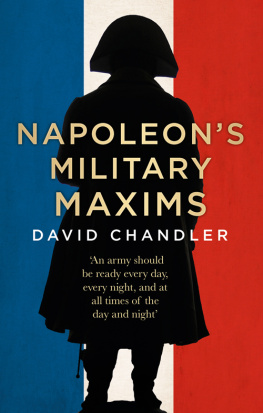

NAPOLEON HAS BEEN CALLED A GIANT FOR THE AGES, AND HIS INFLUENCE resonates to this day not only in the field of military endeavor but also in law and governance. His military maxims, captured here in Napoleons Art of War, provide clear and concise insights into the great leaders thoughts on war. Although they are rooted in their era and circumstances, the maxims are in fact timeless principles applicable to many aspects of life and all forms of competition requiring leadership, management, and industriousness. To contextualize each of the seventy-eight pithy maxims, General Burnod provides brief explanatory expositions. As a result, this slim volume contains a surprising wealth of information on military strategy. Immensely popular since they first appeared in print soon after his death, Napoleons military maxims have helped enshrine him as one of historys Great Captains and a father of modern warfare.

Napoleon Bonaparte was born on the island of Corsica in 1769 to an Italian-speaking family of minor nobility. Corsica had been ceded to France by Genoa only a year prior to his birth, and consequently Napoleons worldview was somewhat different from that of his countrymen. He received a lieutenants commission just as France was convulsed by the bloody revolution of 1789. The young Napoleon saw his genius matched by fortuitous timing as the nation began to grant favor based on individual merit and not simply birth. Further, the times provided him with ample opportunities to prove his worth. He held his first significant command of troops at the siege of Toulon when he was twenty-four years old, and his first command of a complete army two years later when he conquered northern Italy and forced Piedmont, Sardinia, and Austria to sue for peace. The bureaucrats in Paris recognized his success in the field, and Napoleon rose swiftly through the ranks and received commensurate responsibility. After leading a large expedition to Egypt and Palestine in 1798, he returned to Paris the following year and seized power in a nearly bloodless coup. France had suffered for several years under an inept revolutionary government and now was linked completely with its young (he had just turned thirty), charismatic, and driven First Consul. Over the next fifteen years, Napoleon transformed not only France but, indeed, much of Europe, and he conducted warfare in a mode that had profound consequences for generations to come. In 1804, he declared himself emperor to solidify his control and fought ten major military campaigns while simultaneously serving as Frances supreme political leader. Arguably his greatest victory came at Austerlitz, where he defeated the combined forces of the emperors of Russia and Austria in 1805. His subsequent string of victories led him to overreach somewhat in the summer of 1812 when he invaded Russia. The campaign that followed led to the deadly retreat from Moscow that severely depleted both his human and logistical resources. Finally defeated by the combined powers of Europe at Waterloo in 1815, and consigned to an exile on the island of St. Helena in the cold South Atlantic, Napoleon spent his remaining years burnishing his image and legend. He was always his own best biographer and publicist, leaving countless musings to be lovingly transcribed by his disciples, including more than one hundred maxims on a variety of topics. The maxims pertaining to warfare are presented in this volume. Although they transcend the military aspects of warfare, they capture the essence of how Bonaparte conducted campaigns and battleshis art of war.

Both contemporaries and historians have described Napoleon as one of the most competent human beings who ever lived. His intellect was penetrating and incisive. His interests were truly catholic in their variety of concerns. His mind was mathematical in its analysis; geometry was an abiding love of his, and calculations were an essential part of his being. Napoleon was a master of detail. His superhuman capacity for work ensured that in a very short period he stamped an everlasting imprint upon France and Europe. His energy shook off the cobwebs of inertia prevalent in French society, and invigorated reforms in all facets of French lifegovernment, economy, civil law, church, education, and military. Whether these new concepts were products of the Revolution or emanated directly from him, Napoleon took them and molded them into legislation. The concrete manifestations of these ideas, imposed by Napoleon, penetrated not only France but spread across much of Europe and reached across the Atlantic. A later reaction against them could not return the world to a status quo ante. This profound and irrevocable impact is Napoleons fundamental legacy.

This volume follows the form of an early edition translated into English by Colonel (later Lieutenant General) Sir George C. DAguilar, CB, a combat-tested British infantry officer. DAguilar had received his commission in 1799 and served for more than fifty years in numerous campaigns on several continents. His translation, completed in 1831 and including annotations by the French General Burnod, is the most frequently cited and updated of the many versions of Napoleons military maxims. Burnod first selected and published his version of the maxims no later than 1827, and they were quickly translated into German, Italian, Spanish, and English. The maxims, in all their various guises, have been consistent best sellers for nearly two centuries. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars many soldiers, both generals and foot troops, old and young, had an inclination to write about the great events in which they had participated. The outpouring of works concerning the military aspects of the period is simply astonishing. The influence upon following generations is equally so. Many writers simply wanted to describe their own experiences, but just as many wanted to capture and distill the methods of warfare that had been unleashed by Napoleon and his contemporaries. They found fodder for their enterprises in Napoleons own words and in the study of his campaigns and battles. Most significant in this regard was the work of two soldier-theorists, Karl von Clausewitz and Henri Jomini, both of whom titled their works The Art of War. Jominis work was more influential during the first century following Napoleons demise, whereas Clausewitzs has been the focus of the second. Their works, as well as compilations of the maxims, exposed thousands of officers to Napoleons art of war. Jominis influence on officers in the American Civil War, for instance, is undeniable, and Stonewall Jack-son, himself a superb practitioner of warfare, carried a copy of the maxims on campaign.

The word maxim means far more than simply a saying or proverb when applied to Napoleons ideas. His maxims are instead formulations of basic principles and rules of conduct, and thus are important elements of his war-fighting philosophy. Yet they are not truths to be slavishly applied in every circumstance. Each situation is unique unto itself and demands equally unique leadership decisions and actions. Like the principles of war, a collection of nine axioms also derivative mainly from the Napoleonic epoch, the maxims are to be understood as guideposts. Strict adherence to each principle or maxim is not required or even always appropriate to a given situation; however, their neglect is taken at the leaders peril. The maxims are not simply a set of pithy rules and commonsense aphorisms. They are distillations of a preeminent leaders hard-earned battlefield wisdom. Napoleon was a prolific letter writer, often keeping four or five secretaries busy as he dictated on a variety of subjects, and the maxims mirror his advice and directions given in letters and orders while on campaign. We can still find relevant themes and ideas of value in their systematic reflections. Technological change has made the battlefield quite different from that of Napoleons day, yet much remains the same, especially where the individual is concerned. Field Marshal Earl Arthur Wavell, one of Britains greatest twentieth-century soldier-scholars, recognized this. In his