I received plenty of help during the many years I spent researching this book, starting with readers like my wife, Preble, and the anonymous reviewers of The University of Alabama press. Most crucial was the warm hospitality provided by my family and friends who had the bad luck of living close to archival deposits. Among them were Nathalie and Emmanuel Blanc, Marcel Blanc and Michelle Berny, Ronald and Elizabeth Cook, Coralie Dedieu, Jacques and Marie-Madeleine Girard, Sophie and Guillaume Larnicol, and Nicolas Vercken. They have earned my eternal gratitude and a warning that future research projects might force me again to monopolize their couch. My research trips were funded in part by mcNeese State University's Evelyn Shaddock Murray grant, Shearman grant, Joe Gray Taylor grant, and Violet Howell faculty award, the Library Company's PEAES fellowship, and a Gilder-Lehrman fellowship. I gratefully thank these institutions for their financial support. I would also like to single out employees of the Library Company of Philadelphia, the University of Florida's special collections, and the French naval archives in Vincennes for being particularly knowledgeable and friendly.

Introduction

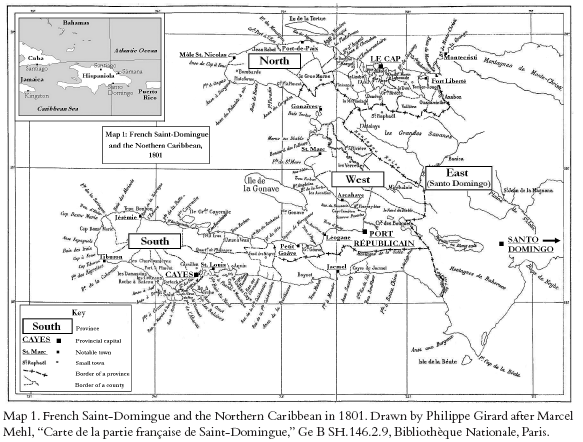

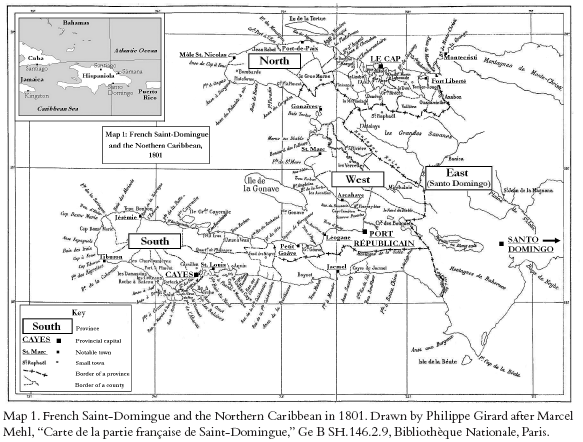

Cape Smana, at the northeastern corner of the island of Hispaniola, was still a sparsely inhabited wilderness when on January 29, 1802, a small group of riders arrived at full gallop. His name was Toussaint Louverture; he was a former slave; but he now governed in the name of the French Republic all of Hispaniola, the second-largest island in the Caribbean (present-day Haiti and Dominican Republic).

As he flew toward his destination, Louverture's thoughts probably drifted two thousand leagues across the ocean to Paris and his direct superiors. Eight years before, revolutionary France had emancipated most of the slaves in its colonies, but Louverture's increasingly autonomous rule had raised many eyebrows and he knew that his enemies were openly calling for his removal from office. Six weeks before he had learned from Jamaica that France had just signed a peace protocol with England, an important development that now made it possible for France to send a fleet to overthrow him.

The arrival of the French fleet was the reason why Louverture was now urging his horseprobably Bel Argent, his favorite mountnorth and east. He had to see for himself how many troops France had sent to rein him in. If he was lucky, France had sent one lone agent onboard a lowly corvette, whom he would control as easily as he had controlled previous French envoys. But there was always the possibility that France might have used the suspension of hostilities with England to send several frigates carrying hundreds of troops. Louverture's large army would probably dominate them, but even a few hundred of Napolon Bonaparte's soldiers were a force to be reckoned with.

The sight that greeted Louverture as the bay of Smana finally came into view must have taken his breath away. Below him, lying at anchor, sailed three corvettes, eleven frigates, and ten vaisseaux (ships of the line), the largest warships of their time, each of them carrying upwards of one thousand sailors and troops. There was worse: far to the east, surging from the sea like monsters from the depths of hell, Louverture could see more vessels arriving, their sails seemingly blanketing the horizon from one end to the other. By the time these reached Smana a few hours later, the combined fleet totaled nine transports of various kinds, nineteen frigates, twenty-two of the massive vaisseaux, and over twenty thousand men and women. Only God knew how many more stragglers were still on their wayand given the magnitude of the catastrophe befalling him, Louverture must have been tempted to abandon the Catholic version for the Vodou (voodoo) bon dieu of his Creole upbringing.

The fifty ships maneuvered to form three parallel lines and began ferrying hundreds of troops from one vessel to another, obviously in preparation for a landing. As night fell each ship lighted three fires to signal its position, and the scintillating armada, reflected on the Caribbean swells, now seemed three hundred strong under the myriad flickering dots of the starlit sky.

Louverture correctly guessed that the main landing would take place more than two hundred miles to the west in Cap Franais or Cap (present-day Cap Hatien), the largest city of the colony. Reaching Cap in time to warn its commander was of the highest importance. Should Cap fall intact, the French would have sufficient resources to mount a massive, coordinated offensive throughout Saint-Domingue. Louverture's rule, maybe even his life, would come to an end, but there was even worse to fear. Bonaparte had not sent two-thirds of the French navy solely to overthrow an elderly governor. His ultimate goal, Louverture suspected, was to restore slavery. If he was right, the freedom of four hundred thousand men, women, and children was at stake.

Egging Bel Argent down the hill, Louverture began galloping toward Cap. As a young slave, he had been entrusted with the care of the plantation's horses, and he was known as the best horseman in the colony; his entire life had prepared him for this very moment. In a desperate, headlong run, he flew west along the coast, racing the French fleet to Cap. If he won, he might successfully oppose the French landing and save both his rule and his people's imperiled freedom; if he lost, his entire world would come crashing down. The Haitian war of independence had begun.

To a contemporary audience, the land in which the Haitian Revolution took place brings to mind voodoo spells, Tontons Macoutes, and boat peoplenothing worth fighting over. Two centuries ago, however, Haiti, then known as Saint-Domingue, was a sugar powerhouse that stood at the center of world trading networks. All the great statesmen of the time, from Thomas Jefferson to Bonaparte, spent much of their waking time, not worrying about an influx of Haitian illegal immigrants, but battling for a share of the colony's exports. Money, not surprisingly, was the reason. Contemporary Haiti might be the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, but late eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue was the