Acclaim for Madison Smartt Bell's

Toussaint Louverture

Well-researched and elegantly written. Bell's portrait of Louverture is as honest as his overall assessment of his actions is generous.

The Wall Street Journal

Absorbing and inspired. Bell creates a world of complicated racial politics, high stakes diplomacy and a time of world change.

The Times-Picayune (New Orleans)

Mesmerizing. Moving. Combines rich, lyrical prose with exhaustive detail.

Essence

A well-researched and timely reminder that Haiti's political tra vails are no recent phenomenon.

The Miami Herald

An important recounting of a little-known piece of history.

The Washington Post Book World

Bell's very readable and scholarly biography unpacks the complexities of [Louverture] and his milieu.

The Providence Journal

A readable and engaging narrative, one likely to become the standard biography in English about this remarkable figure.

The Nation

A beautifully composed discourse on a revolutionary world, a work in a class all its own. Like any great novelist, this biographer respects the inscrutability of human nature, thereby elevating the genre of biography to the highest level.

The New York Sun

MADISON SMARTT BELL

Toussaint Louverture

Madison Smartt Bell is the author of twelve novels and two collections of stories. All Souls' Rising was a finalist for the National Book Award and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. A professor of English and the director of the Kratz Center for Creative Writing at Goucher College, Bell lives in Baltimore, Maryland, with his family.

ALSO BY MADISON SMARTT BELL

Lavoisier in the Year One

The Stone That the Builder Refused

Anything Goes

Master of the Crossroads

Narrative Design

Ten Indians

All Souls' Rising

Save Me, Joe Louis

Doctor Sleep

Barking Man and Other Stories

Soldier's Joy

The Year of Silence

Zero db and Other Stories

Straight Cut

Waiting for the End of the World

The Washington Square Ensemble

Aux grands marrons!

Yves Benot

Gerard Barthelemy

Michel Rolph Trouillot

Toussaint Louverture, placed in the midst of rebel slaves from the beginning of the revolution of Saint Domingue, thwarted by the Spanish and the English, attached to the French, attacked by everyone, and believing himself deceived by the whole world, had early felt the necessity of making himself impenetrable. While his age served him well in this regard, nature had also done much for him One never knew what he was doing, if he was leaving, if he was staying; where he was going or whence he came.

Gnral Pamphile de Lacroix

Does anyone think that men who have enjoyed the benefits of freedom would look on calmly while it is stripped from them? They bore their chains as long as they knew no better way of life than slavery. But today when they have left it, if they had a thousand lives they would sacrifice them all rather than to be again reduced to slavery We knew how to face danger to win our liberty; we will know how to face death to keep it.

Toussaint Louverture

Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

AFTERWORD

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Laurent Dubois, Jacques de Cauna, Albert Valdman, and David Geggus for their extraordinarily generous help in straightening me out on numerous specific points but these scholars are not to be held responsible for the conclusions I then drew. I thank Marcel Dorigny, Laennec Hurbon, Jane Landers, and Alyssa Sepinwall for their aid and comfort. Grand merci et chapeau has to Fabrice Herard and Philippe Pichot for a very educational visit to the Fort de Joux.

Introduction

As the leader of the only successful slave revolution in recorded history, and as the founder of the only independent black state in the Western Hemisphere ever to be created by former slaves, Franois Dominique Toussaint Louverture can fairly be called the highest-achieving African-American hero of all time. And yet, two hundred years after his death in prison and the declaration of independence of Haiti, the nation whose birth he made possible, he remains one of the least known and most poorly understood among those heroes. In the United States, at least until recently, the fame of Toussaint Louverture has not spread far beyond the black community (which was very well aware of him and his actions for two or three generations before slavery ended here). Neither Toussaint's astounding career nor the successful struggle for Haitian independence figures very prominently in standard history textbooksdespite, or perhaps because of, their critical importance from the time they began in the late eighteenth century to the time of our own Civil War.

In his own country, Toussaint Louverture is honored very highly indeedbut not unequivocally. In the pantheon of Haitian national heroes, Toussaint is just slightly diminished by the label Precursor of liberty and nationhood for the revolutionary slaves who took over the French colony of Saint Domingue. The title Liberator is reserved for Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the general who took Toussaint's place in the revolutionary war, who presided over Haiti's declaration of independence from France, and soon after crowned himself emperor. It's true enough that Dessalines was the first man across the finish line in the race for liberty in Haiti. But without Toussaint's catalytic role, it's unlikely that Dessalines or anyone else would have known how or where to enter that race.

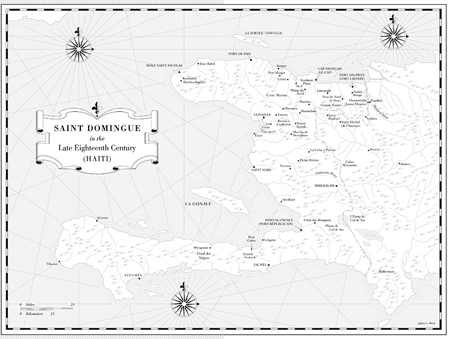

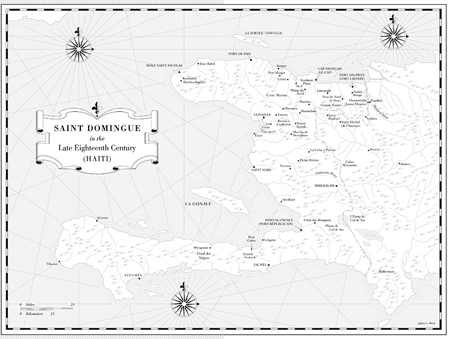

Today's Haiti, known until 1804 as French Saint Domingue, occupies the western third of the island of Hispaniola, or Little Spainthe name that Christopher Columbus gave it when he first arrived in 1492. The 1.3 million Taino Indians who already lived there called their homeland Ayiti, which means mountainous place. Most of the Indians were peaceable Arawaks, though a community of more warlike Caribs had settled, comparatively recently, on an eastern promontory, in what is today the Dominican Republic.

Hispaniola was not the first landfall in the New World for Columbus's expedition, but it was the first place where he built a settlement on land, beginning with timber from one of his three ships, the Santa Maria, which had foundered in the Baie d'Acul, on Haiti's northwest coast. After their long, cramped voyage of uncertain destination, Columbus's sailors and soldiers may well have felt that they had blundered into paradise, especially since in the beginning the Arawaks received them as gods descended from the sky. Food grew on trees and the living was easy. The awestruck Arawaks were friendly, their women agreeably willing. The Spaniards were fascinated, among other things, by the pure gold ornaments these natives wore.