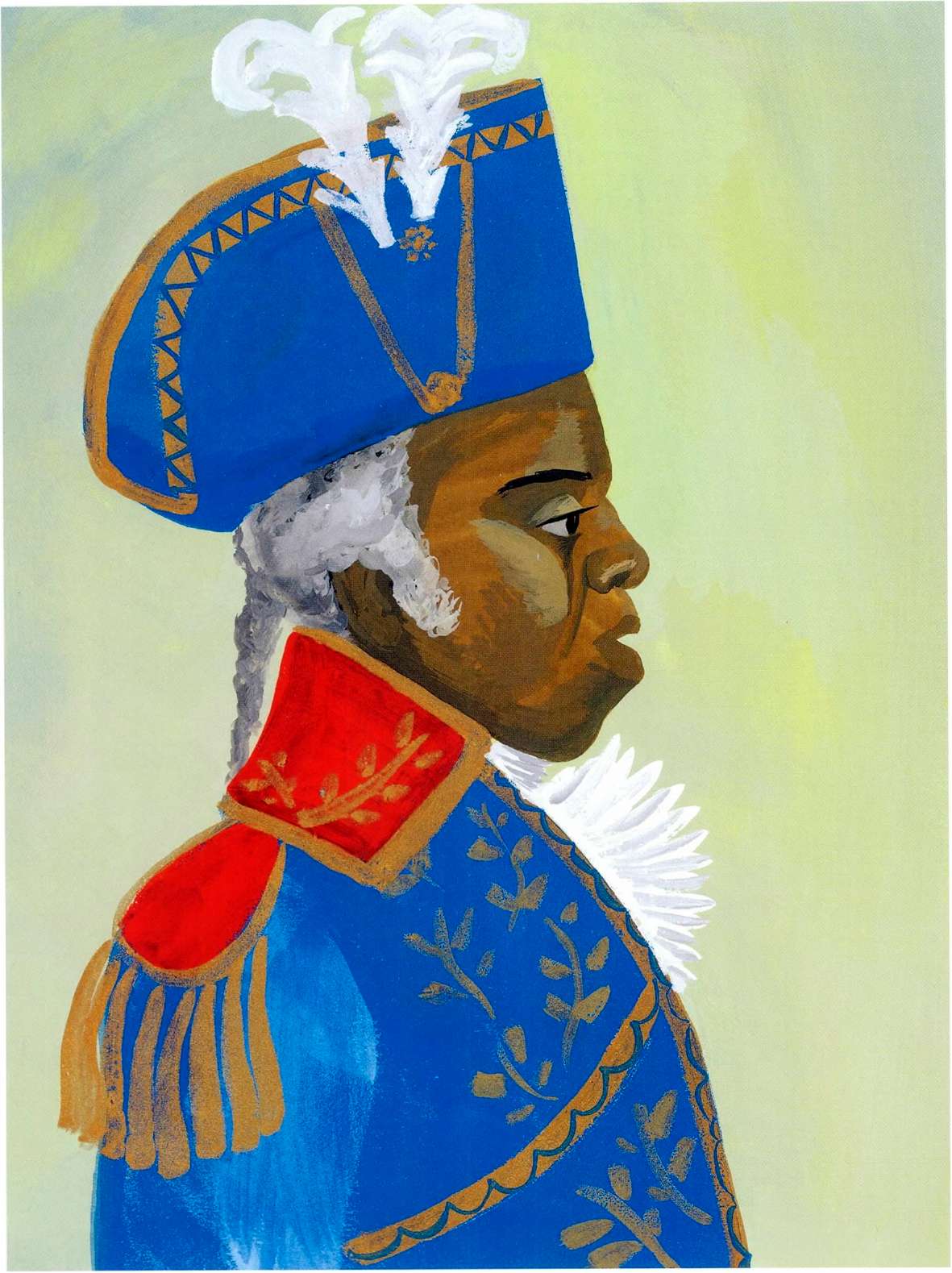

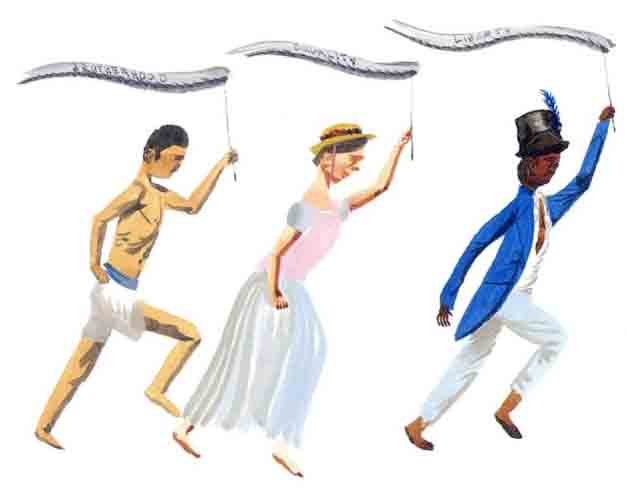

Illustrated by R. Gregory Christie

H OUGHTON M IFFLIN B OOKS FOR C HILDREN

H OUGHTON M IFFLIN H ARCOURT

B OSTON 2009

Text copyright 2009 by Anne Rockwell

Illustrations copyright 2009 by R. Gregory Christie

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Houghton Mifflin Books for Children is an imprint of

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhbooks.com

The text of this book is set in Fournier.

The illustrations are gouache on Strathmore illustration board.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rockwell, Anne.

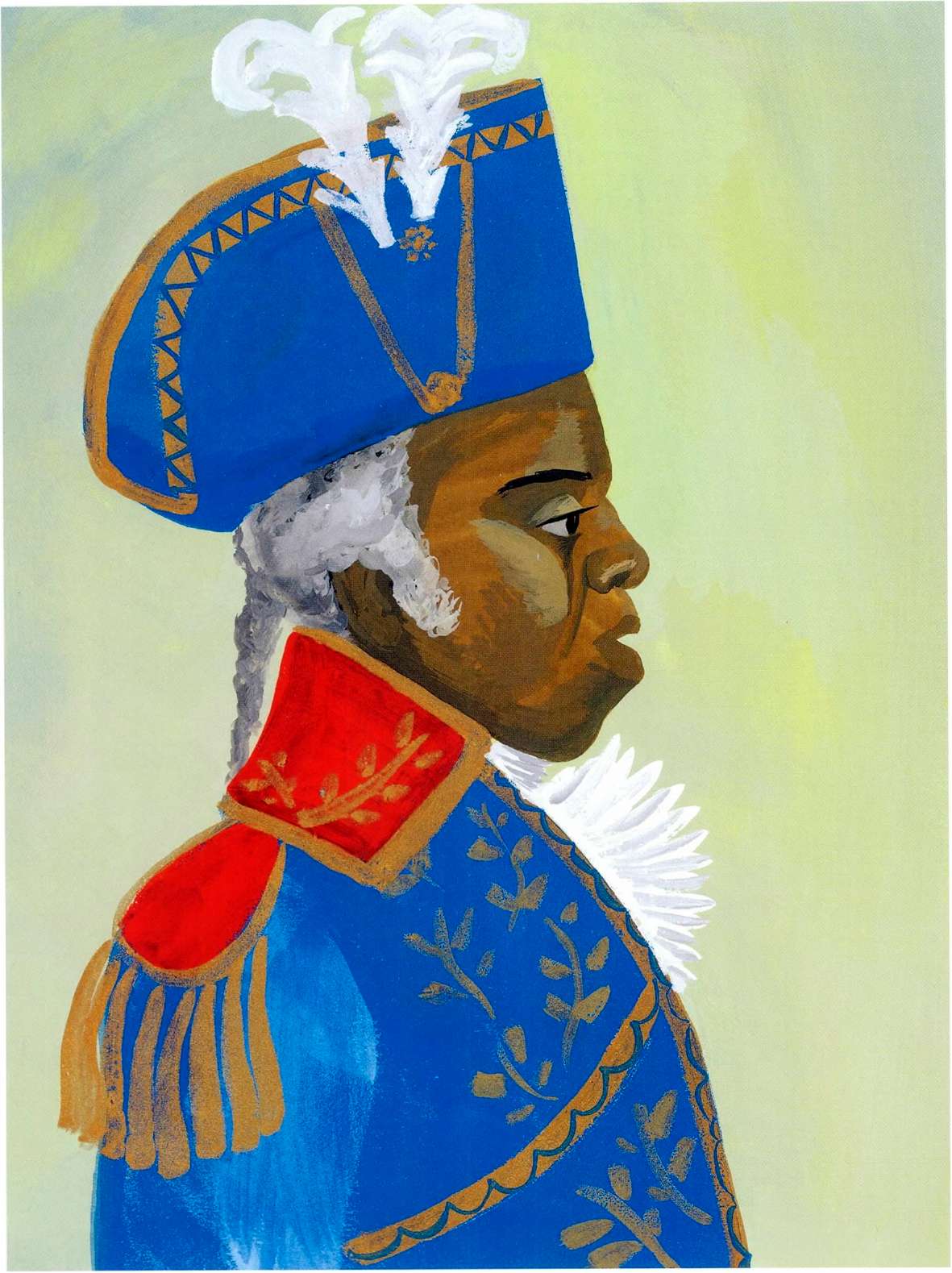

Open the door to liberty! : a biography of Toussaint L'Ouverture /

by Anne Rockwell ; illustrated by R. Gregory Christie.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-618-60570-5

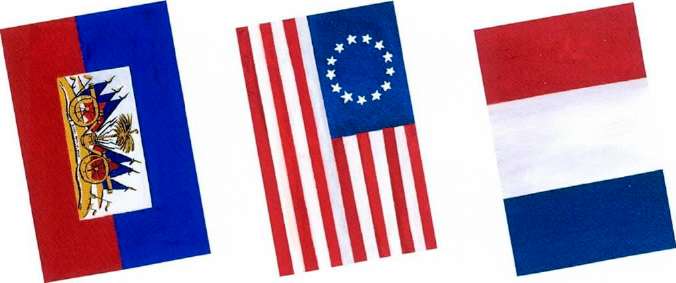

1. Toussaint Louverture, 1743?1803Juvenile literature. 2. Haiti

HistoryRevolution, 17911804Juvenile literature. 3. Revolutionaries

HaitiBiographyJuvenile literature. 4. GeneralsHaitiBiography

Juvenile literature. I. Christie, Gregory, 1971. II. Title.

F1923.T69R63 2007

972.94'03092dc22

[B] 2007025746

Printed in China

WKT 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Eveline

A.R.

For Martine and Angie

R.G.C.

Preface

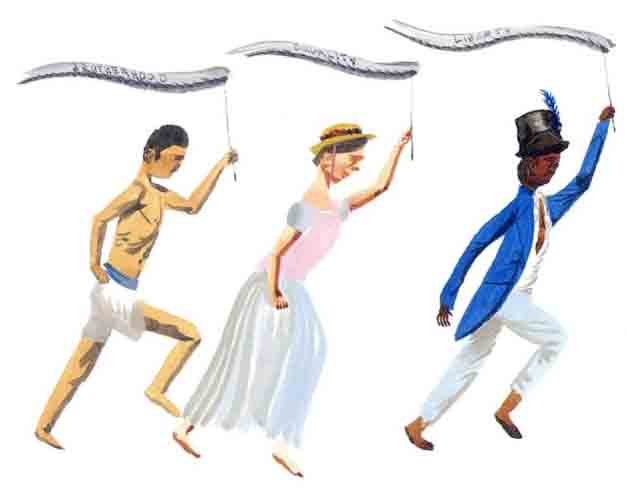

Many brave and remarkable people came before us. Those who helped us become the best we can be should never be forgotten. One such hero was a black man with a French name who was born a slave on an island in the Caribbean Sea. We don't hear much about him today, but what he did changed his world and ours. He opened the door to liberty for black people everywhere. His actions helped make the United States the world power it is today.

This is his story.

Little Stick

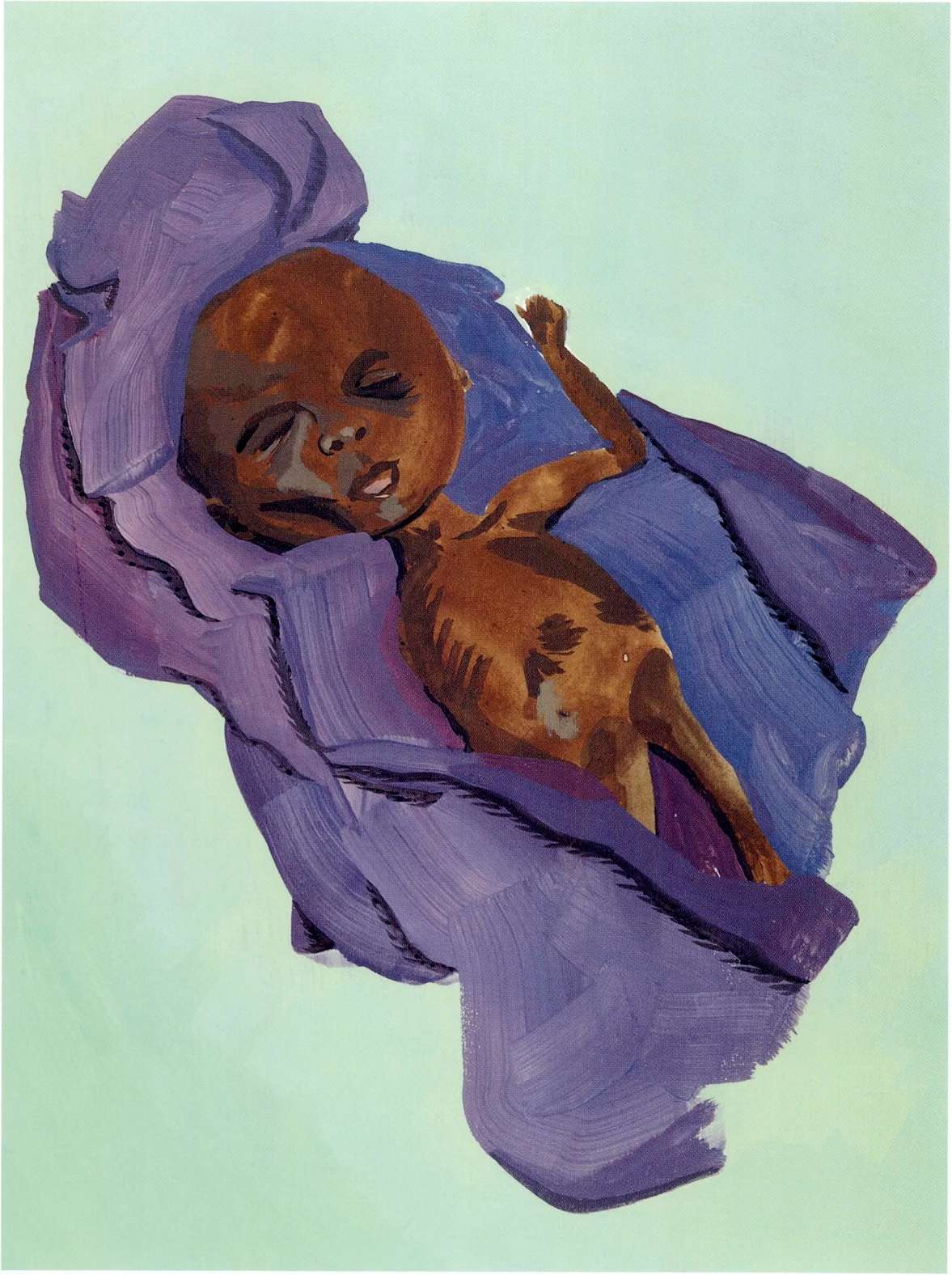

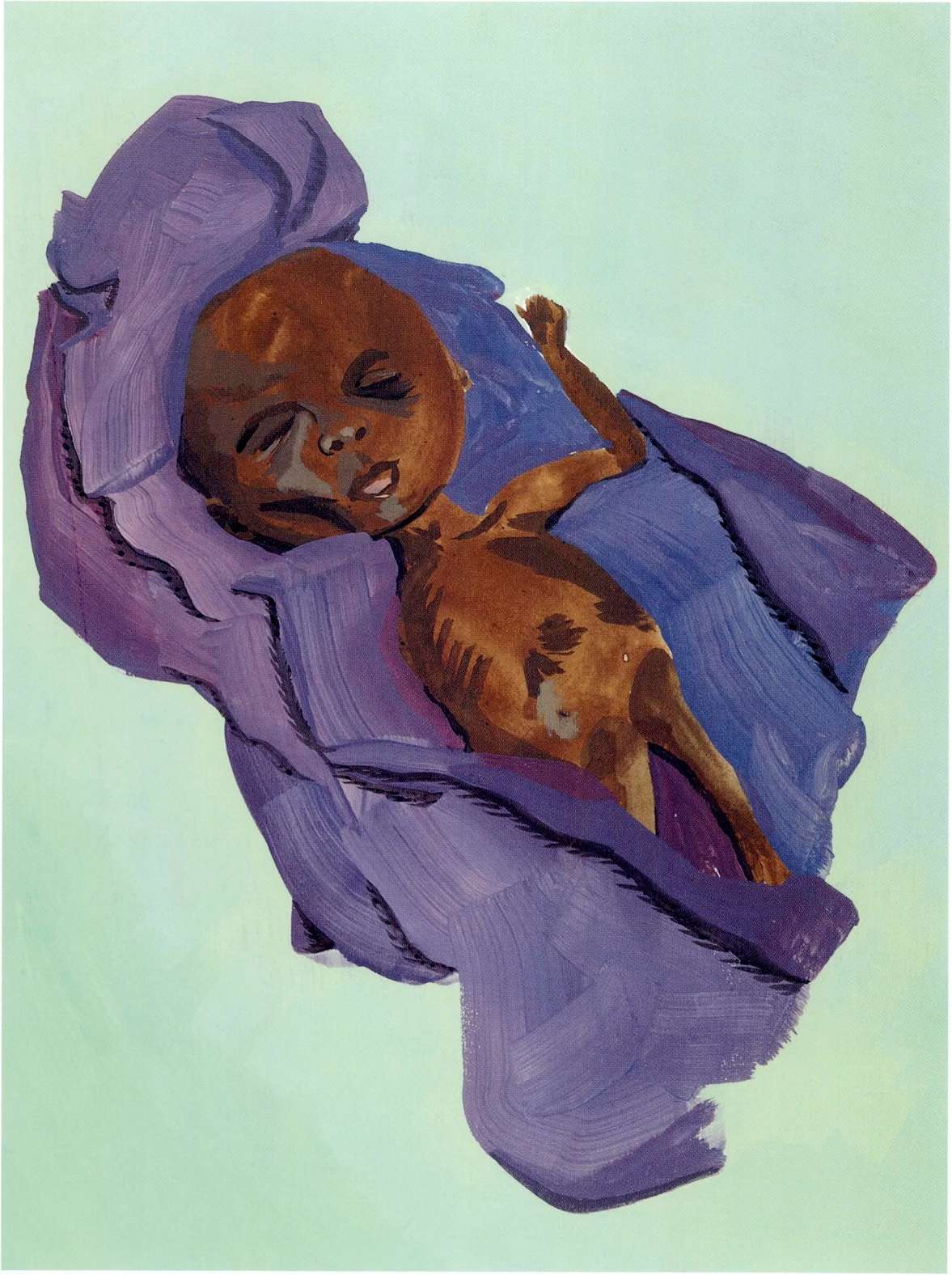

In about 1743 a skinny, puny baby boy was born on the island of St. Domingue in the Caribbean Sea. Both his parents were slaves who'd been born in West Africa. Before their baby was born they had consulted a wise woman, an African-born slave who knew how to communicate with the powerful spirit world. She predicted that their son would be very special. She said he would grow up to be more than a man. He would be a nation.

As with all messages from the spirits, the meaning of this one was not entirely clear. And when the baby was born, it seemed as though the wise woman's prediction was wrong. Everyone was sure he would die soon after he was born. But that baby boy arrived with great determination. He fought for life, and won. He hung in day after day until he was christened Francois-Dominique Toussaint Breda. No birth records were kept for slaves, but his birthday may have been November 1, since that is All Saints Day, or La Toussaint in French. His name was French because his island was a colony of France. His last name was Breda after the plantation where he was born.

Although his parents called him Toussaint, the other slave children nicknamed him "Little Stick." That's because he was as skinny as the thinnest branches of the ebony trees that grew on the fertile island.

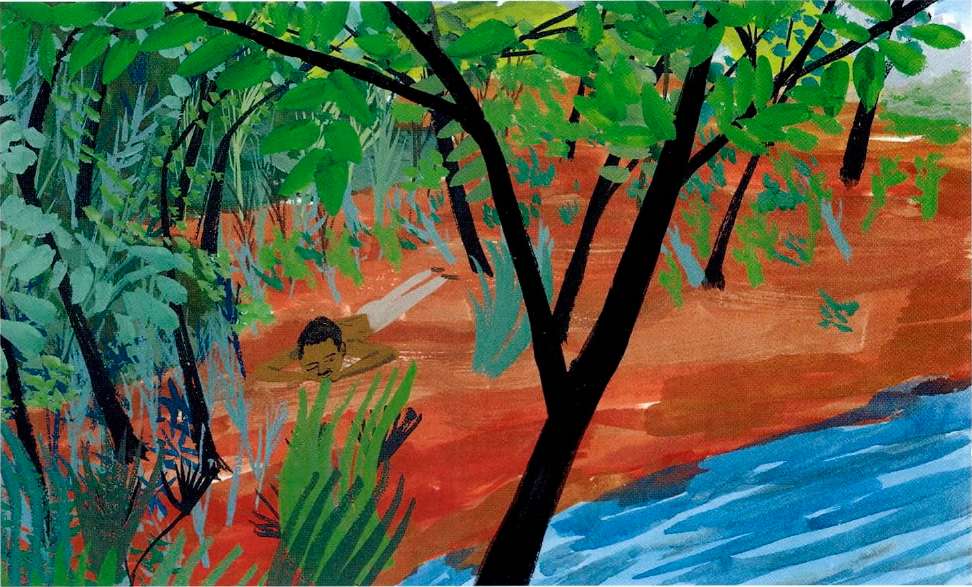

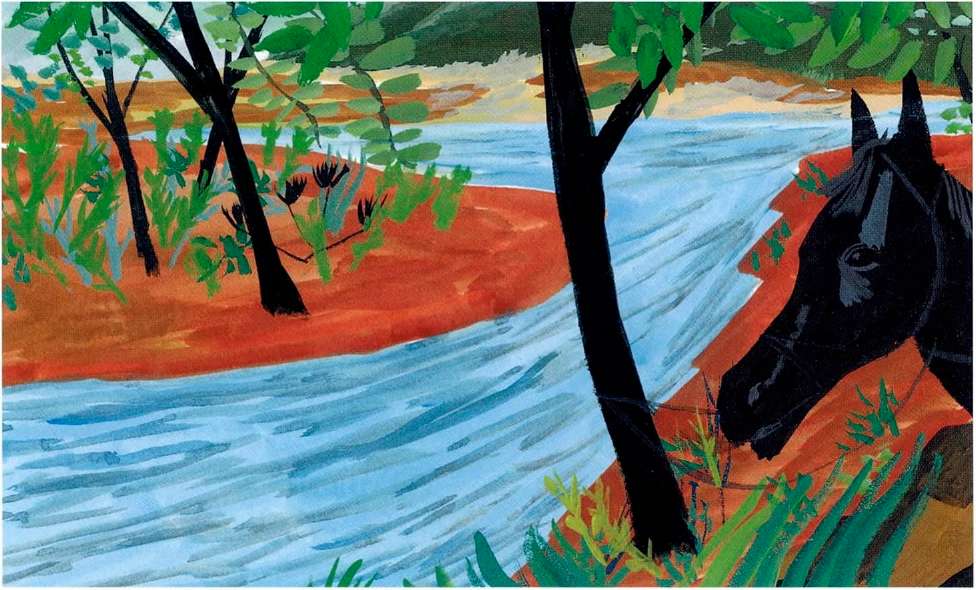

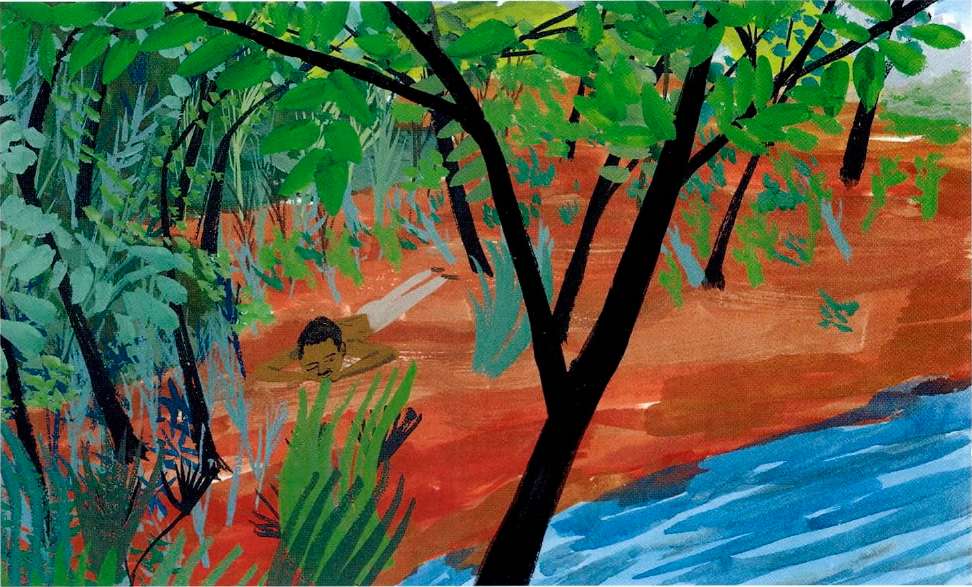

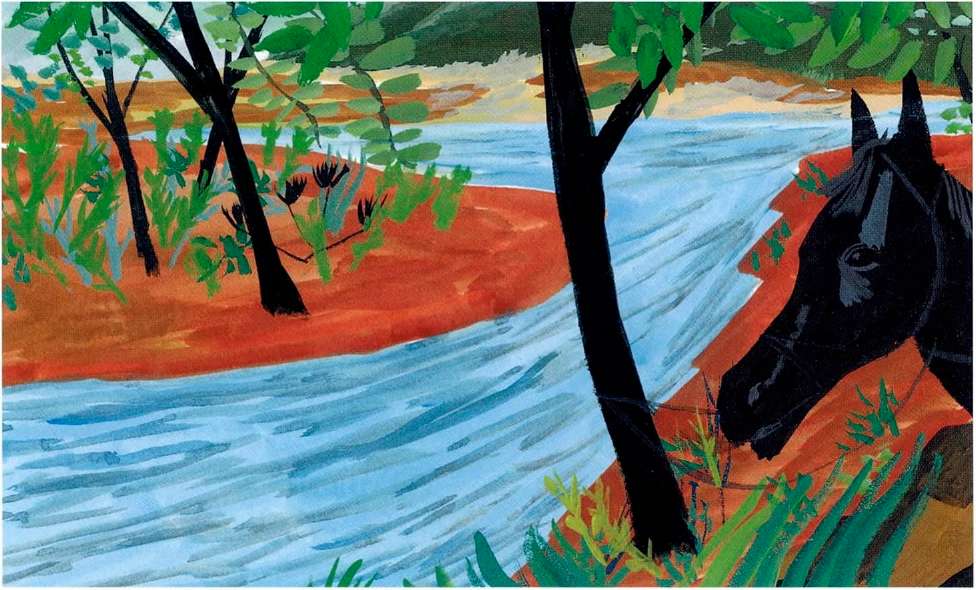

Toussaint didn't want to be called "Little Stick." He wanted to be as strong as a great tree. Every day he swam across rivers and rode horseback until he was exhausted, and every day he rode and swam farther than he had the day before. He never did get very tall, but he did get mighty strong.

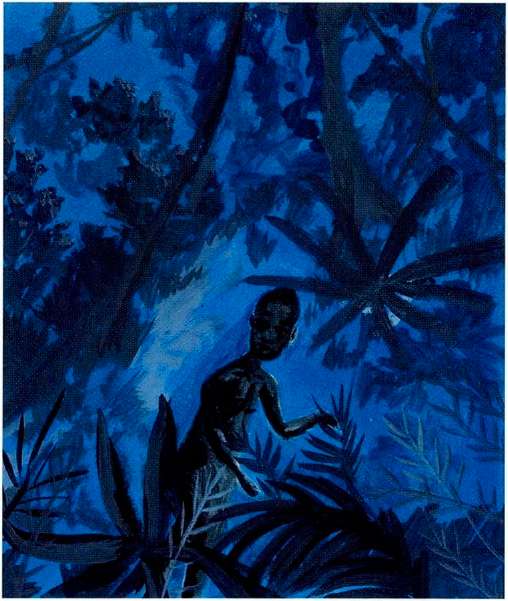

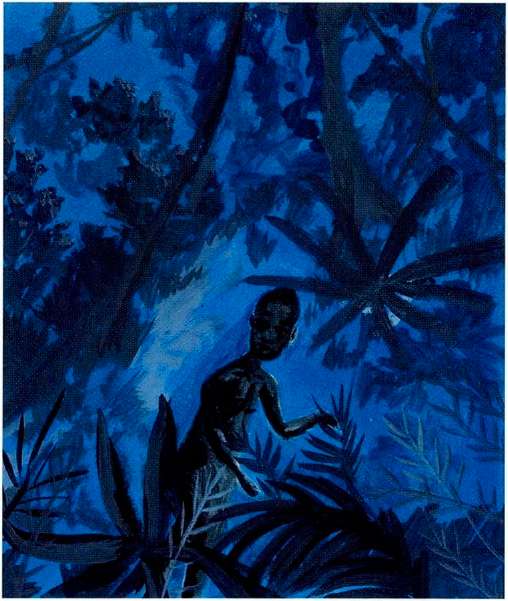

He was also a quiet and mysterious child who everyone believed was deep and wise. He liked to seek out quiet places where he could be alone with his thoughts.

Gaou-Guinou, his father, was a prince of the Aradas tribe and had been captured in war, sold into slavery, then brought to St. Domingue. His master treated him differently from most slaves because of his noble manner. He and his wife, Pauline, lived near the Breda plantation on their own landand led a life little different from those of free people.

Their first son was also more fortunate than most slave children. Toussaint was never whipped or mistreated. He lived with his parents and his seven younger brothers and sisters on a comfortable farm. He had a godfather who was a freed slave, a man named Pierre Baptiste Simon. Baptiste had learned to read from Catholic priests and in turn taught Toussaint, for he recognized how remarkably intelligent this child was.

Even so, Toussaint knew the cruelty that other slaves suffered. He saw slave ships in the harbor unloading their chained and brutalized human cargo. He saw what happened when slaves dared to revolt.

In 1759, when Toussaint was about sixteen years old, a man named Franois Mackandal did rebel. He was one of a group of people called Maroons (which comes from the word cimarron, meaning "wild" in Spanish). Maroons were slaves who ran away repeatedly, who refused to work no matter how badly they were beaten, who would sooner die than live as slaves. Their owners often gave up and let them be as long as they stayed away from the other slaves and didn't cause trouble. They lived behind tall fences in isolated villages high in the mountains.

But Mackandal broke the rules Maroons were supposed to live by. Late at night he visited plantations and persuaded slaves to join him in his plan of poisoning the masters, then seizing power over the plantations. By day he mixed kettles of poison in a secret cave. He distributed packets of the dried and powdered poison to his followers in the dead of night. His followers slipped it into the soup bowls or wineglasses of their masters and mistresses.

About six thousand white plantation owners and managers died before any white person found out about Mackandal's plot. Finally one of his followers was tortured until he talked. Mackandal was taken prisoner and brought to the main square in the island's largest city, Le Cap, where he was burned at the stake in front of crowds of slaves. One was Toussaint.

He watched flames destroy Mackandal. Other slaves insisted their hero was not dead but had flown away in the form of a mosquito. They believed he would come again.

Meanwhile, the young Toussaint was allowed to read any books he wanted in the library of the big house. One was by Julius Caesar, the Roman general who'd conquered a neighboring people called the Gauls. Toussaint learned that there had been slaves in Rome. They hadn't come from Africa, and they weren't black. He then understood that slavery wasn't simply a matter of color. White people could be slaves, too. One of those long-ago Roman slaves, named Spartacus, had led a rebellion against the great Roman armya rebellion that had come close to victory.

Next page