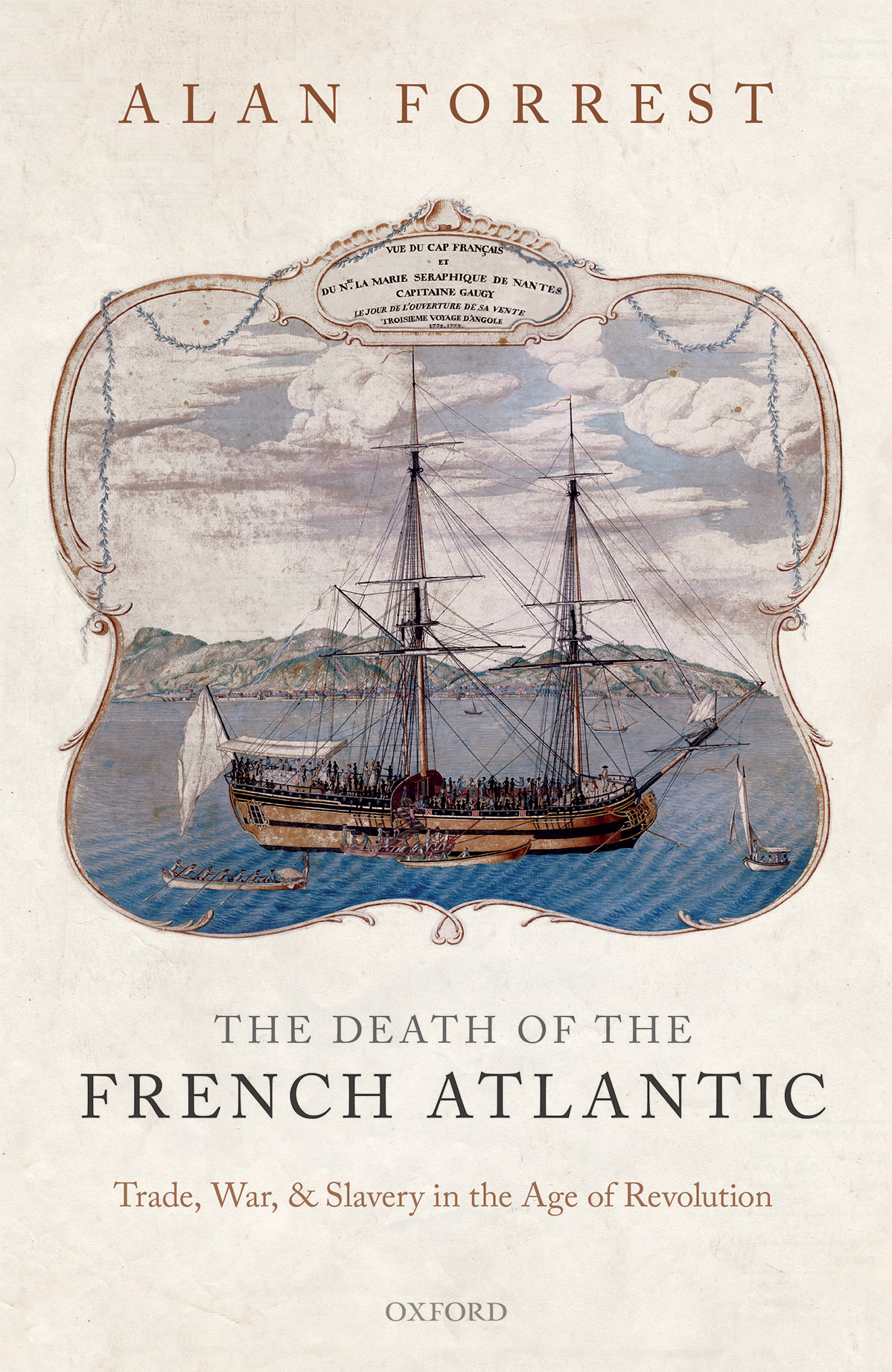

The Death of the French Atlantic

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Alan Forrest 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2020

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019946182

ISBN 9780199568956

ebook ISBN 9780192570734

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Rosemary and Marianne

Preface: The Death of the French Atlantic?

Until relatively recently, most historians shared the view that the French Revolution was directly responsible for the decline in French commercial fortunes that followed. This was especially true of the French Atlantic and its principal port cities. The last decades of the monarchy were looked back upon rather fondly as the peak years of prosperity, while the Revolution was associated with economic neglect and a damaging indifference to the interests of trade. It was a period when commercial values were decried, the mercantile classes were undermined, and Frances colonies were lost to war or revolt. For some of the earliest historians of the port cities, like the nineteenth-century chroniclers Aurlien Vivie and the abb OReilly in Bordeaux, an anti-revolutionary, or anti-Jacobin, stance fitted well with their own political views and with their admiration for the work of commercial elites, and they did not hesitate to denounce the Revolution as the source of many of the woes of their own century.

The opinions of nineteenth-century historians reflected in large measure those of the cities merchants and commercial elites, who saw themselves as the victims of revolutionary prejudice and Parisian manipulation, and who did not hesitate to speak in apocalyptic terms of the crisis they faced. Any decline in the volume of trade would affect the commercial cities particularly severely, they warned, leaving their quays empty and their dockworkers idle. If opinion on the colonies does not change, insisted the two deputies sent from La Rochelle to the National Assembly in 1792, Frances trade will be completely lost. They added, rather plaintively, that a major cause of the current crisis lay in the ignorance of commerce that was shown by the Assembly itself. For, they maintained, the people of Paris, and with them members of the National Assembly, have unfortunately no concept of the importance of these precious islands and of the part they play in establishing our national credit.

The merchants warning was stark: if Atlantic commerce flagged, the threat of misery and unemployment hung over entire communities, with the direst consequences for the poor and vulnerable. This warning was not new, but it became more strident as the Revolution approached. In 1788, for instance, the Chamber of commerce in Bordeaux had talked of the fragility of trading conditions and had expressed fears that the threatened loss of the citys Parlement would have disastrous effects on the market in luxury goods. Theirs was a deeply conservative and paternalistic view of society, where everything depended on the expenditure of the most affluent. The rich built houses and initiated public works, they argued, and they kept the citys economy vibrant by their consumption, providing the food and housing for ordinary working families. As a result, the stonemason, the joiner, the carpenter, the locksmith, the blacksmith, the sculptor, the plasterer, the roofer are all kept in work; money circulates; and it keeps society alive. Without it, they implied, their cities would crumble, families would starve, and workers would be forced to migrate back to the countryside from which they had come. The booming Atlantic economy that had promoted their prosperity would die.

This was, needless to say, a gross exaggeration, made with the intention of spreading anxiety and alarm. But in all the Atlantic ports there was a shared sense of apprehension, a belief that the Revolution spelt the end of an era, heralding an uncertain future. Nowhere was this felt more deeply than in Nantes, where the economy was dangerously dependent on slaving and where the interests of family and commerce were often interlocked, whether in the commercial activities of the port or on the plantations of Saint-Domingue, creating frequent family entanglements between the people of Nantes and refugees fleeing from the Caribbean. Nantes simply could not ignore events in the Caribbean islands, so great was its dependence on trade in slaves and colonial produce. Before the Revolution, the West Indian trade had dominated mercantile life in the city, while after the Revolution the presence of refugees from the Caribbean was a constant reminder of the bonds that had tied the city to the Creoles and their economy. Many could not conceive of their city without the Atlantic trade, and when the Napoleonic Wars were finally over in 1815, Nantes merchants rushed to despatch their vessels to West Africa and to reopen trade routes with the Caribbean. Such over-dependence on one market and on a single form of commerce would prove also to be their undoing.

In the other ports, the dependence on slaving and the Caribbean was less intense. In Bordeaux, for instance, the citys prosperity was spread across a wider range of commercial activities: slaving, of course, in the form of the triangular trade with West Africa and the Caribbean; but also direct trade with the West Indian islands, voyages to India and the East Indies, a valuable entrept trade in colonial produce with other parts of Europe, and wine exports to Britain and the Baltic. This gave the city greater flexibility in the face of crisis, and Bordeaux merchants showed more initiative in seeking out new markets in the nineteenth century. But the extent of its economic resilience can easily be overstated. Over the course of the eighteenth century, a series of naval wars had repeatedly threatened Bordeauxs prosperity, and from 1792 France would again be involved in nearly a quarter-century of warfare. Franois Crouzet is surely right to underline the fragility of the citys prosperity and the critical importance of keeping open Bordeauxs shipping lanes to the Caribbean. It was based upon structures that invited the jealousy of other European powers and could easily be undermined by war. Given the weakness of the French Empire, he writes, an accidental and artificial creation to which public opinion remained largely indifferent, which was not supported by adequate maritime strength and whose economy was tied to the vicious practice of slavery, Bordeauxs prosperity was fragile. It is a truth that had already been exposed by the Seven Years War and would be again, though to a lesser degree, in the later 1770s with the war over American independence.