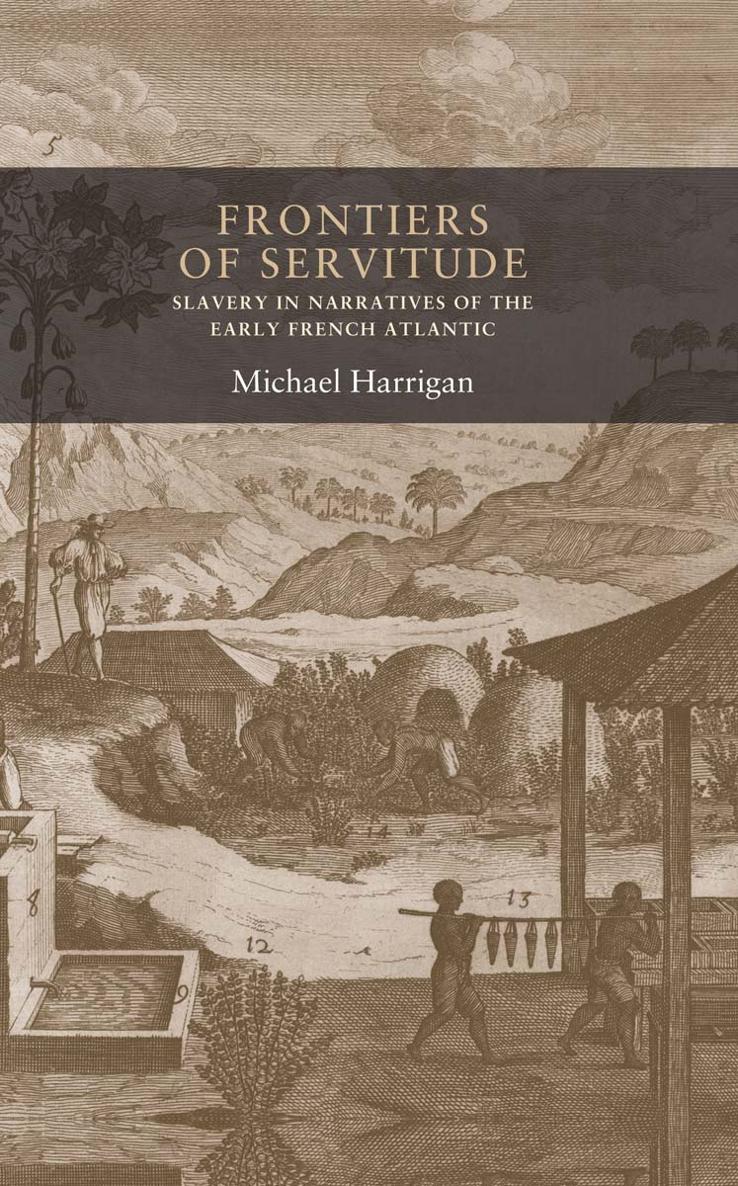

Frontiers of servitude

SEVENTEENTH- AND EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY STUDIES

General Editor

Anne Dunan-Page

Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Studies is a collection of the Socit dtudes Anglo-Amricaines des XVIIe et XVIIIe sicles promoting interdisciplinary work on the period c.16031815, covering all aspects of the literature, culture and history of the British Isles, colonial and post-colonial America, and other British colonies. The series welcomes academic monographs, as well as collective volumes of essays, that combine theoretical and methodological approaches from more than one discipline to further our understanding of the period and geographical areas.

Previously published

Radical voices, radical ways: Articulating and disseminating radicalism in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Britain

Edited by Laurent Curelly and Nigel Smith

The challenge of the sublime: From Burkes Philosophical Enquiry to British Romantic art

Hlne Ibata

English Benedictine nuns in exile in the seventeenth century: Living spirituality

Laurence Lux-Sterritt

Frontiers of servitude

Slavery in narratives of the early French Atlantic

Michael Harrigan

Manchester University Press

Copyright Michael Harrigan 2018

The right of Michael Harrigan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 2226 1 hardback

First published 2018

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset in 10/12 Sabon by

Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire

Dedicated to the memory of Leo T. Harrigan

Contents

This book has benefited from the support of a number of colleagues and institutions. Funding and a period of research leave from the University of Warwick were invaluable for carrying out research at several archives in France. I would like to thank Karine Bnac-Giroux and Coline-Lee Toumson for their welcome at seminar and conference presentations at Universit des Antilles, and at Domaine de Fonds Saint-Jacques, Martinique in 2014 and 2015. Thanks also to the Socit dtudes Anglo-Amricaines des XVIIe et XVIIIe sicles. The manuscript of this book was read by a number of anonymous reviewers, for whose helpful suggestions I would like to express my gratitude. Thanks also to the staff at Manchester University Press, particularly Emma Brennan, Paul Clarke and Alun Richards.

Particular thanks are due to L. A., to my mother Edie, and to Constanza and Francis. This book is dedicated to the memory of my father Leo, who loved life, and from whom I learned its most important lessons.

Translations into English are my own, unless otherwise indicated. Quotation of original texts in French has been limited when an original is available in a modern, online or facsimile source. Original quotations in French from restricted archival material have generally been included in notes. The spelling of quotations in French has been modernised but, to facilitate referencing, the titles of sources have been transcribed using the original spelling. The following abbreviations have been used for archival or unpublished material:

| AdC | Archives dpartementales du Cher, Bourges |

| AJPF | Archives jsuites de la Province de France, Vanves |

| ANOM | Archives nationales doutre-mer, Aix-en-Provence |

| ARSI | Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Rome |

| ASPF | Archivio Storico di Propaganda Fide, Rome |

| BM | Bibliothque Mazarine, Paris |

| BnF | Bibliothque nationale de France, Paris |

| MdC | Mdiathque de Carcassonne Agglo, Carcassonne |

It was February 1694, in the north of the island of Martinique. Pre Labat had arrived in Macouba to an enthusiastic welcome. In the recently constructed church, aided by two altar-boys, he had said Mass before the small community of French colonists. After his sermon, he asked his parishioners for a list of the names of those to be prepared for the sacraments. These were children of communion age, and those adult slaves (or as Labat wrote, ngres adultes) who had not yet been baptised who required instruction. He implored his parishioners to let him know whenever anyone became ill in the future. Day or night, in good or bad weather, he said, he would be always ready to assist them as soon as he was called; if he was obliged to be away from the parish on other business, his sacristan would know where to find him. These words, the priest noted, were appreciated by everybody. At the end of the Mass, after a baptism, all of his parishioners were at the door of the church, and gave him great thanks for his promises of help. In turn, they assured him, they would make sure to carry out the other instructions the priest had made during the Mass.

The rest of the day continued in a similarly welcoming vein. Accompanied by most of the attendees to his presbytery, he received assurances that they would contribute to financing the enlargement of the building. Invited to dine at the house of a Captain Michel, Labat was offered the use of Michels own horse. During lunch, the neighbouring cleric, Father Breton, arrived, greeted Labat warmly, and joined the company. After a long, pleasant meal, the Captain and others began to play cards (Labat, somewhat coyly, refused to participate, but consented to Michels offer to put half of what he might win aside for him or for furnishings for the presbytery). Labat stayed for supper (another generous meal) and was lodged, he says, in an excellent room. The Michel family were to prove of further assistance. Having noticed that Labat was suffering from a skin irritation caused by ticks, the lady of the house sent a female servant to pick a selection of herbs and leaves and to boil them. Before going to bed, Labat writes, a bowl containing the mixture was brought, and his feet and legs were washed. This treatment was repeated over the following days, much of which Labat passed in social visits, interspersed with religious offices and, following a visit to Michels sugar plant, designing a garden for the captain.

The account of Labats arrival in his new parish which has been summarised here figures in his copious description of the Caribbean, the Nouveau Voyage, which would be published in the early 1720s.

These passing mentions of unnamed slaves illustrate the fundamental absences within first-hand accounts from the era of early modern slavery. Much of the specificity of human interaction, from the gestures and expressions of slaves and colonists, or the uses of language, to the subjectivities of the participants, is lost to the textual record. Slaves, in Labats account, seem to be undifferentiated as they carried out their labour, delivering messages, washing feet and announcing arrivals. The concentrated labour which enabled the planters comfortable existence on the islands seems to be hinted at, obliquely. Michels sugar plant deserves the briefest of mentions, while the most striking feature of another of