Contents

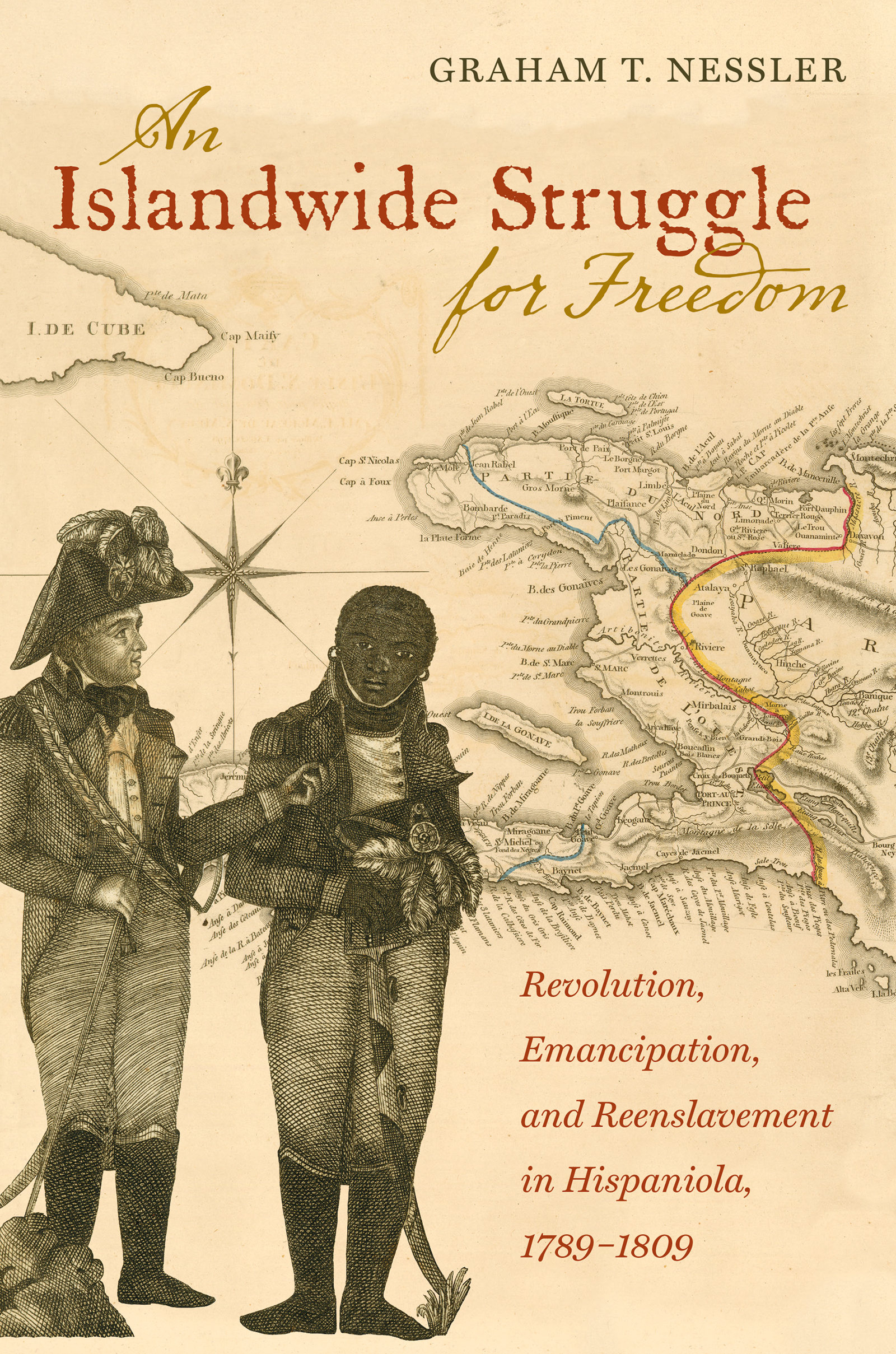

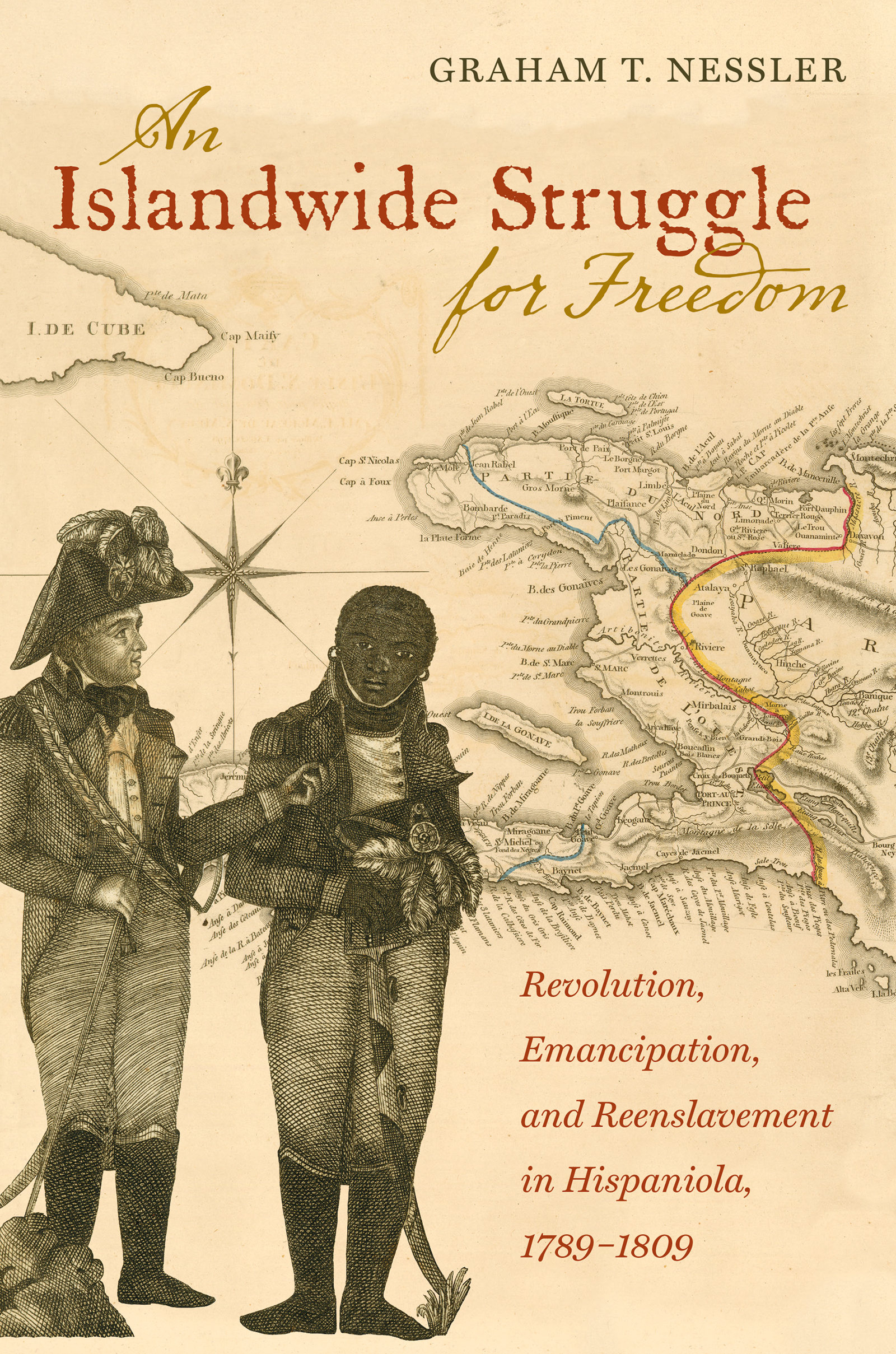

An Islandwide Struggle for Freedom

This book is published with the assistance of the Authors Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2016 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Arno by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Cover illustrations: Map of Hispaniola from 1796 by Nicolas Ponce in Recueil de vues des lieux principaux de la colonie francoise de Saint-Domingue (Paris, 1971); and General Hdouville speaking with a black officer (possibly Toussaint Louverture), both courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nessler, Graham T., author.

Title: An islandwide struggle for freedom : revolution, emancipation, and reenslavement in Hispaniola, 1789-1809/Graham T. Nessler.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015047523| ISBN 9781469626864 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469626871 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SlaveryHispaniolaHistory. | SlavesEmancipationHispaniola. | SlavesHispaniolaSocial conditions. | SlaveryLaw and legislationHispaniolaHistory. | HispaniolaHistory18th century. | HispaniolaHistory19th century. | HaitiHistoryRevolution, 1791-1804. | Dominican RepublicHistoryTo 1844.

Classification: LCC HT1081 .N47 2016 | DDC 326/.809729309034dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015047523

Portions of this book previously appeared as Arrancar el rbol de la libertad: Una interpretacin de la era de Toussaint Louverture en Santo Domingo, 18011802, from Estudios Sociales 40, no. 151 (2012): 1131, used by permission; They always knew her to be free: Emancipation and Re-Enslavement in French Santo Domingo, 18041809, Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies, 2012, Taylor & Francis Ltd., www.tandfonline.com, reprinted by permission of the publisher; The Shame of the Nation: The Force of Re-Enslavement and the Law of Slavery under the Regime of Jean-Louis Ferrand in Santo Domingo, 18041809, New West Indian Guide 86, nos. 12 (2012): 528.

To my mother and father

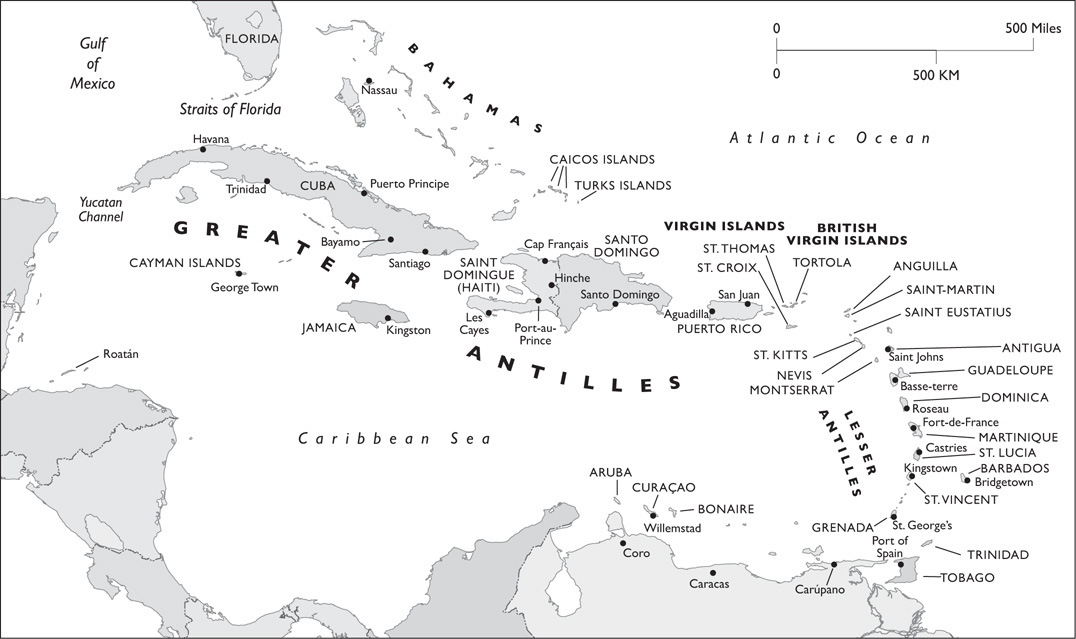

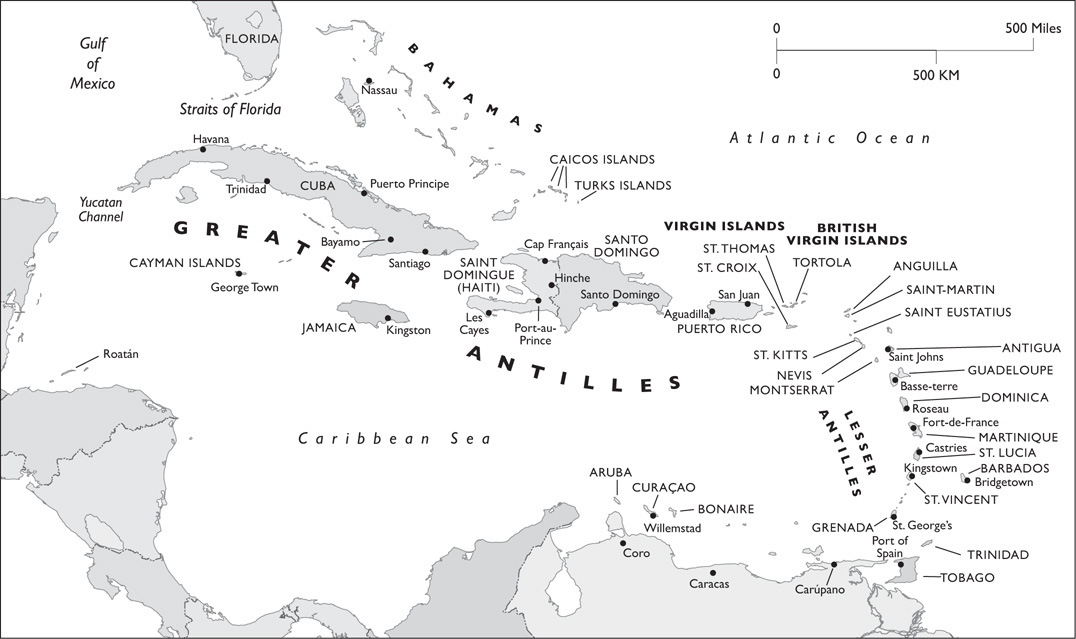

MAP 1. Greater and Lesser Antilles, 1789. Adapted by permission of Indiana University Press from a map with the same caption in Geggus and Gaspar, A Turbulent Time.

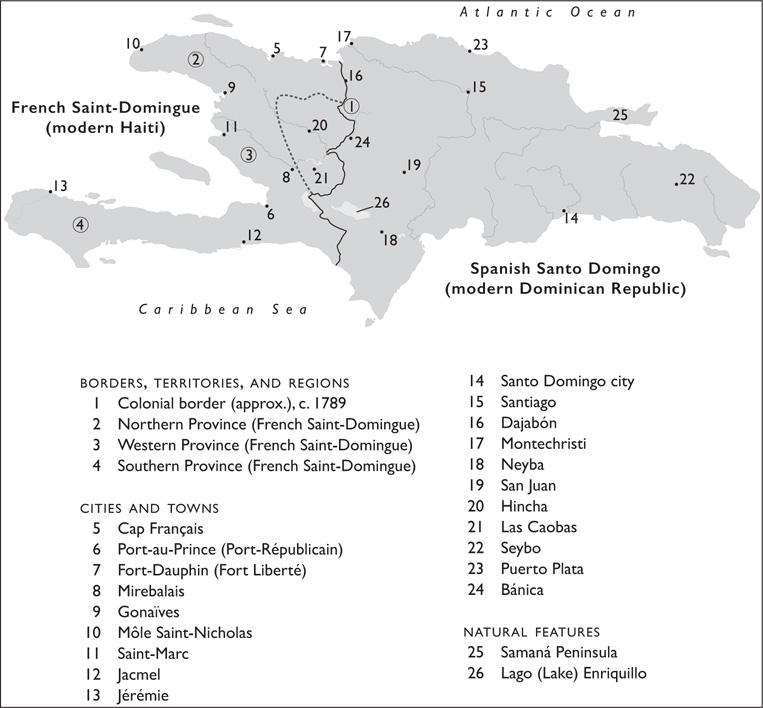

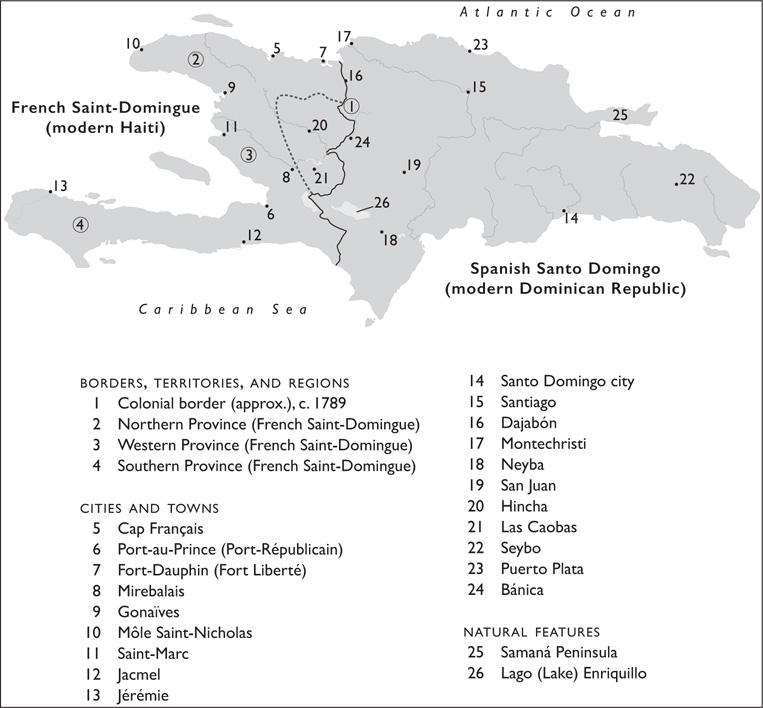

MAP 2. Hispaniola: Key Points of Interest. The solid line indicates the modern political border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The dotted line represents where the colonial border of 1789 diverged from the modern border.

Contents

Maps and Figures

MAPS

1 Greater and Lesser Antilles (1789)

2 Hispaniola: Key Points of Interest

FIGURES

1 Ville de St. Domingue (1754)

2 Vue de la baye du Fort-Dauphin. Isle St. Domingue (1791)

3 El ciudad[a]no. Heudoville habla al mentor de los Negros sobre las malas resultas de su revelin (1806)

4 Carte de lIsle St. Domingue dresse pour lOuvage de M. L. E. Moreau de St. Mry Dessine par I. Sonis (1796)

5 Gnral Ferrand. Il mourit victime de lingraditude (1811)

6 Desalines Primer Emperador de Hayti en dia de Gala (1806)

7 A Plan of the Route of the British Army against the City of Santo Domingo, which surrendered on the 6th July 1809 (1810)

Acknowledgments

Many individuals and institutions gave generously of their time, resources, and moral support to help enable this projects completion. Though I am pleased to use this space to thank many of them, it would be impossible to list here all those individuals who have positively influenced this study in some way. What follows is thus by necessity condensed, and I regret any omissions. Any errors or faults contained in the following work are solely mine.

I first thank my colleagues whose insightful feedback proved integral in shaping this project. Legal scholars Sam Erman and Malick Ghachem offered thoughtful assistance on legal and other aspects of this book, while the careful analysis of fellow Caribbean and Latin American scholars Julia Gaffield, Anne Eller, Francisco Moscoso, Ada Ferrer, John Garrigus, Dominique Rogers, and Sigfrido Vzquez Cienfuegos also proved invaluable. I am also grateful to Lindsey Gish, a specialist on African history, and Marlyse Baptista, a linguist, for their much-appreciated aid and moral support. I also thank my mentors Richard Turits, Rebecca Scott, Paulina Alberto, Laurent Dubois, Jean Hbrard, Ghachem, and Baptista for their advice and encouragement.

As with any project of this scope, a number of institutions and their dedicated staff played key roles at critical junctures in the books evolution. The research that forms the basis for this book was enabled with the generous funding of the French governments Chateaubriand Fellowship and the Social Science Research Council. The staff of all of the archives and libraries mentioned in the bibliography were generous and efficient allies in the research for this study. I also thank the organizers of conferences at which I presented scholarship deriving from this project, such as the University of Michigan Law School, the Centre International de Recherches des Esclavages of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CIRESC-CNRS) in France, and the Dominican Studies Institute (DSI) based in New York City. Ramona Hernndez, the director of the DSI, is a driving force behind the growing field of Dominican studies in the United States and has been a kind and helpful colleague. Martha Jones and other organizers and fellow members of the Law in Slavery and Freedom Project at the University of Michigan also provided critical fora for scholarly exchange, and several offered useful suggestions on aspects of this book. In addition, a Foreign Language and Area Studies fellowship enabled me to undertake an intensive course in Haitian Kreyl (Creole) in the summer of 2006 at Florida International University. This course benefited my project in ways I did not foresee at the time and introduced me to a new community of scholars and activists.

The University of Michigan and Bentley University offered me stimulating and collegial environments in which to pursue this scholarly endeavor. I thank in particular the leadership, affiliated faculty, and staff of the Institute for the Humanities, the Eisenberg Institute, and the History Department at the University of Michigan (particularly Kathleen King, who truly went above and beyond the call of duty). I also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Gesa Kirsch, Cyrus Veeser, Marc Stern, and other Bentley faculty as well as the staff of the Jeanne and Dan Valente Center for Arts and Sciences at Bentley, particularly Janice McMahon.

My colleagues at Florida Atlantic University have also been very supportive. I am grateful for the opportunity that this institution provided me during a transitional phase in my career.