2005 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

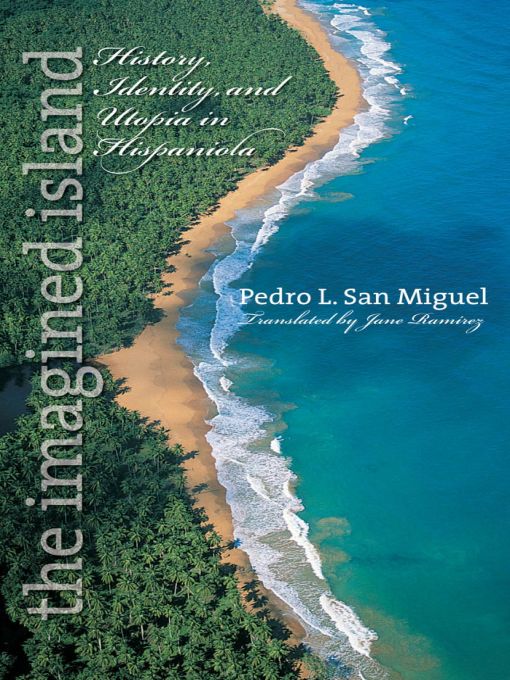

Originally published in Spanish with the title

La isla imaginada: Historia, identidad y utopa en

La Espaola, 1997 Editorial Isla Negra and

Ediciones Librera La Trinitaria.

Set in Scala type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

Translation of the books in the series Latin America in Translation / en Traduccin / em Traduo, a collaboration between the Consortium in Latin American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University and the university presses of the University of North Carolina and Duke, is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

San Miguel, Pedro Luis.

[Isla imaginada. English]

The imagined island : history, identity, and utopia in Hispaniola / Pedro L.

San Miguel ; translated by Jane Ramrez. p. cm.(Latin America in translation/en traduccin/em traduo)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8078-2964-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8078-5627-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

eISBN : 97-8-080-78769-9

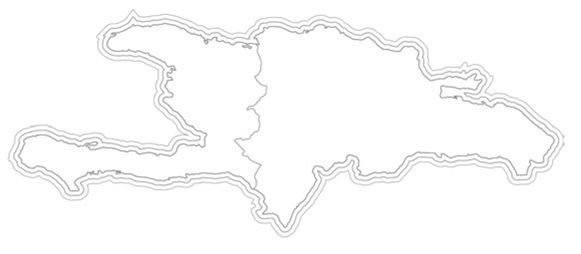

1. Dominican RepublicHistoriography. 2. HaitiHistoriography. 3. HaitiForeign public opinion, Dominican. 4. IntellectualsDominican RepublicAttitudes. 5. Public opinionDominican Republic. 6. HispaniolaRace relations. 7. Bosch, Juan, 1909- 8. Politics and literature. 9. Literature and history. I. Title. II. Series.

F1937.5.S2613 2005

972.930722dc22 2005006283

cloth 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1

paper 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1

To

Rafael Emilio Yunn,

Roberto Cass, and

Orlando Inoa,

for many years of

teaching me other

geography and

other history

Identity and utopia are two dimensions of the same problem. Alberto Flores-Galindo, Buscando un inca (Mexico City, 1993)

To respect the wholeness of the past means to leave it open to

inquiry, to refuse to neutralize the contingencies of history by

transforming them into the safe zone of myth.

David K. Herzberger, Narrating the Past (Durham, 1995)

One cannot expect to possess knowledge which does not change

one. Once one knows, then one is acting upon that knowledge,

whether it is to withhold the knowledge from those who would also

be changed, or to give it to them.

Anne Rice, Taltos (New York, 1995)

We can only know the actual by contrasting it with or likening it to

the imaginable.

Hayden White, Tropics of Discourse (Baltimore, 1986)

We look at ourselves in the mirrors of our origins... and we

understand that every discovery is a desire, and every desire, a

need. We invent what we discover; we discover what we imagine.

Carlos Fuentes, Valiente mundo nuevo (Mexico City, 1992)

PREFACE

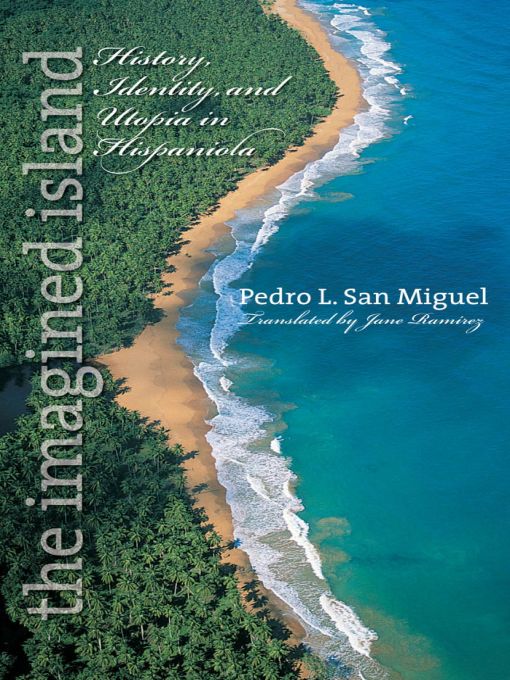

Writing the preface for the English translation of La isla imaginada: Historia, identidad y utopa en La Espaola (San Juan and Santo Domingo: Editorial Isla Negra and Ediciones Librera La Trinitaria, 1997) seems amazing to me. Several years have passed since the University of North Carolina Press decided to include this book in its Latin America in Translation series. On occasion I even thought the publication project was the chimera of a delusional mindmine, of course. But luckily this was not the case, and after a prolonged wait, La isla imaginada has been transformed into The Imagined Island. This metamorphosis has been possible thanks to the endeavors of people to whom I would like to express my appreciation.

Above all, I would like to thank Jane Ramrez. I am fully aware of the hard work and determination she put into translating this book. I hope she is aware of my profound gratitude for her outstanding work. Likewise, I would like to thank Elaine Maisner at the University of North Carolina Press for her help during all these years. I am also indebted to Carlos Roberto Gmez of Editorial Isla Negra and to Virtudes Uribe and Juan Bez of Librera La Trinitaria for their endorsement of the publication of the Spanish version of this work.

In the preface to the Spanish edition, I mentioned numerous friends and colleagues who encouraged and benefited me with their knowledge and acumen. To mention them all here would intimidate the reader. But I feel obliged to name those who have continued to support me since the original publication of La isla imaginada. In Puerto Rico, Eugenio Garca-Cuevas, Silvia lvarez-Curbelo, Carlos Pabn, Humberto Garca-Muz, Fernando Pic, Walter Bonilla, Carlos Altagracia, Jorge Lizardi, Manuel Rodrguez, Alfredo Torres, and the whole gang of Librera La Tertuliathe cervantinos and the serpentinoshave always encouraged me. In the Dominican Republic, Roberto Cass, Emilio Cordero-Michel, Raymundo Gonzlez, and Mu-Kien A. Sang continue to trust my workalthough they sometimes might disagree with it. I likewise cherish their enduring friendship. Elsewhere Flix Matos-Rodrguez, Francisco Scarano, Csar Salgado, and Jorge Ibarra have been friends and enthusiastic readers of my work. I would like to make special mention of Harry Hoetink, hoping that these words reach him as a deeply felt tribute to his outstanding contribution to Dominican and Caribbean studies.

The preface to the Spanish edition was signed in Ro Piedras, Puerto Rico, during the Christmas holidays of 1996. Several things have changed in my life since then. Laura Muoz entered my life from a land far from the Caribbean. Since then, in the Caribbean, Mexico, and elsewhere she has become part of my imaginary geographies, a necessary element of my own personal utopia.

Pedro L. San Miguel

Ro Piedras, Puerto Rico/Tepepan, Mexico City

February 2005

Introduction

A Kind of Sacred Writing

What we have before us is an attempt to write not a factual history,

but rather a sacred one, a narrative in which life must confirm Scripture.

Ral Dorra, Profeta sin honra (Mexico City, 1994)

History is probably our myth. It combines what can be thought, the

thinkable, and the origin, in conformity with the way in which a society

can understand its own working.

Michel de Certeau, The Writing of History (New York, 1988)

The twentieth century was a cornucopia of stories, a kaleidoscope of interpretations. The very abundance of these narratives seems to contribute to those fin de sicle terrors that today beleaguer even the most venerable interpretations. Thus canonized, the content and discursive structures of these narratives are exempt from verification. Ensconced in the sphere of myth, they have become a sort of sacred history.