Also by JULIE A. SELLERS

Merengue and Dominican Identity: Music as National Unifier (McFarland, 2004)

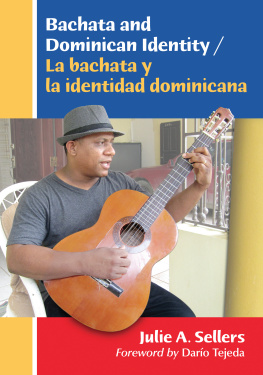

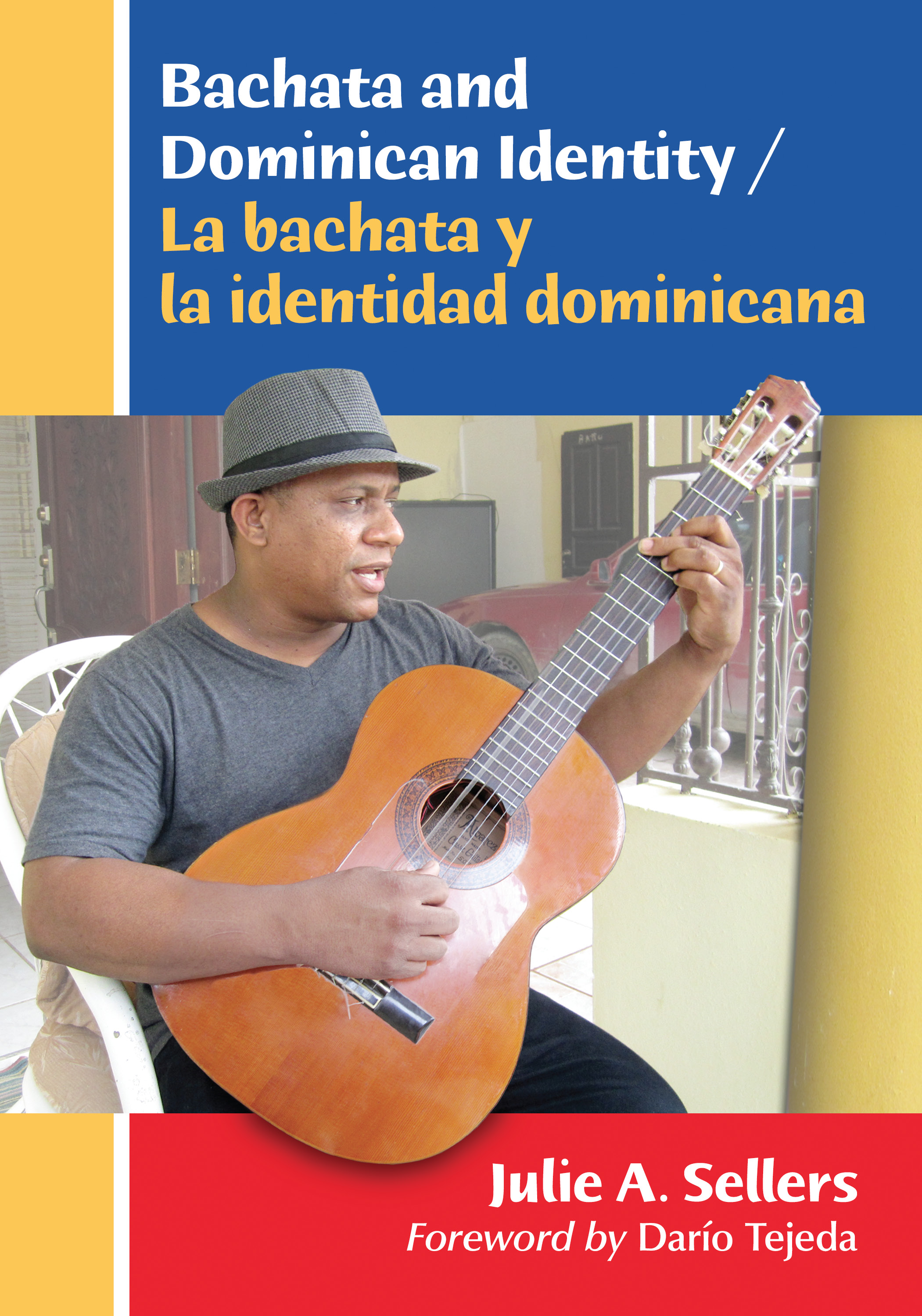

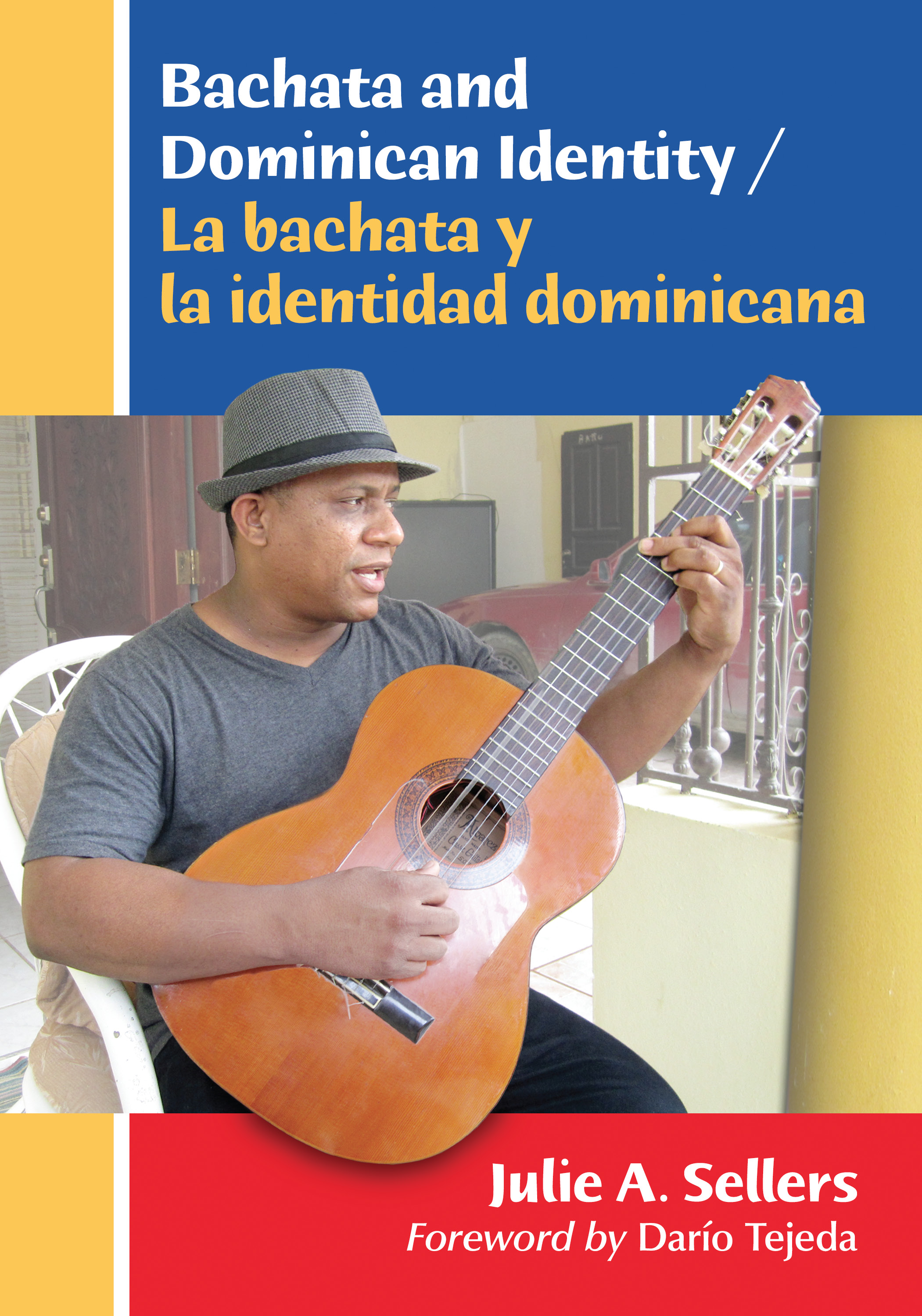

Bachata and Dominican Identity / La bachata y la identidad dominicana

JULIE A. SELLERS

Foreword by Daro Tejeda

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Photographs are by the author unless otherwise indicated

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1638-4

2014 Julie A. Sellers. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: Bachatero and producer Davicito Paredes (photograph by Julie A. Sellers)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my husband,

P.J Vaske,

and in memory of

Rupert,

a good and faithful dog

English

Foreword by Daro Tejeda

I assume the reason Julie Sellers invited me to write this foreword is because of my works related to bachata, beginning with my 1993 biography of Juan Luis Guerra. That text includes my first writings on that style of Dominican music, and I detail the artists ties to the musical genre, as well as the stories behind each of his first bachatas in the tone of a fictionalized biography. I followed this work with my 2002 book, La pasin danzaria (The Passion for Dance), an academic study in which I dedicated a chapter to bachata; this same chapter was later published separately as a bilingual offprint under the Spanish title, La bachata: Su origen, su historia y sus leyendas (Bachata: Its Origin, Story, and Legends).

Here, I will provide the reader with some ideas to help understand the importance of this book, in which the author discusses the aforementioned topics, bachata and Juan Luis Guerra. Her work fits within the framework of what, since 2007 and in a work in progress, I have termed bachatology. I use this concept to refer to a way of thinking about bachata within the context of Dominican and Caribbean culture, and its ramifications around the world, such as its impact in the United States, as Sellers studies in this book, and also in Europe. The authors interest in Dominican music was first revealed in her 2004 book, Merengue and Dominican Identity: Music as National Unifier, and has continued to grow since then. This book is the best evidence of that interest.

A journalist once asked me during an interview what gave rise to my studies of music, an understandable question in a country such as the Dominican Republic that has always allowed itself to enjoy musical expressions almost exclusively in terms of sound, song, and dance. My response was clear: they arise from an interest in thinking about music, and thus, moving beyond merely hearing, singing, or dancing it. For that reason, I began to talk about bachatology, describing it as an exercise in thinking about bachata as a musical and cultural phenomenon.

Indeed, that is what bachatology is about: focusing on bachata as a culture. I would call it bachata culture. This concept could be misleading for the very reason bachata was scorned at first: because it corresponds to a way of being among its musicians and fans who come from the poorest social classes in Dominican society. For that very reason, they are depicted as beingor almost beingilliterate (which includes lacking formal studies of music or voice), and often black or mulatto.

Bachata musicianslos bachateroswere, and are, bearers of a combination of economic, social, political, racial, and educational conditions that defined their profile as those excluded or marginalized from systems of decorum, wealth, power, knowledge, status, and refinement, all variables that intersect with classicist and racial criteria in the Dominican Republic. In bachata, the poor speak, as does the peasant, the black, the urban underprivileged, the forgotten onein sum, he who is oppressed by economic, social, political, and cultural inequalities. This is the Pobre Diablo (Poor Devil) in the bachata by Teodoro Reyes, or the Juancito Nadie (Johnny Nobody) in the song of the same name by Elvis Martnez.

That nobody from the Dominican countryside came dressed as the agricultural day laborer, the small landholder, the farm laborer; and in the city, he was the guard, the watchman, the servant; abroad, he was the cadena reference to the Dominican migrants who returned home wearing chains as physical decorations. Their poverty swept all of them along to a state of indignity (and often, social ruin), which included a poor education that unfairly depicted them as ignorant. For more than half a century, American anthropologist Oscar Lewiss studies have portrayed like none other the circumstances of the poverty-stricken who frequently descends into indigence and is down on his luck.

From this state of poverty, blackness, illiteracy, exclusion and oblivionthat is, of being nobody there arose another state even more sorrowful: one of degradation and discrimination. The bachatero was the victim of a social stigma and cultural prejudice inherited from the long-standing membership of such people in second- or third-rate society in a hierarchy of power. This structure was established by the fashionable set who called themselves the First Class Society until well into the twentieth century.

These autodidact musiciansalmost completely without musical or academic schoolingproduced lyrics that were often lewd and full of sexual double entendres and phallic symbols. They sang these lyrics in an unrefined way and to a rustic musical accompaniment, and whats more, with a beat that was danced in a sexually inciting way in the squalor of rural cabarets and urban suburbs. When confronted with its supposed barbarism, the vigilant gaze of the gods of civilization determined that bachata must have been born in sin. Bachata was born under a pejorative sign as its own name shows. It was music of the common folk, such as that seen in Mexican cinema of the 1940s and 1950s. The musicians themselves, panic-stricken when faced with the social criticism accompanying the stereotypes associated with bachata, were reluctant to accept the name imposed by adversarial voices. Although they tried to make other names popular, they were unable to change the fact that the dominant, mainstream culture named them.

As Sellers emphasizes, Bachatas association first with rural migrants to the city, then with the brothels, and later, with the lower-class domestic workers who listened to it as they did their work, marked it with a stigma that was difficult to overcome. Thus, musical taste became a way to mark class lines, as musician Vicente Garca states in this book.

The obstacles were difficult. Bachata lacked social recognition. It did not possess that quality of social distinction, as observed by Pierre Bourdieu, which served as a sign of a privileged social status linked to societys power structure. The bachateros reacted to this state of being a nobody by means of what Gramsci would have called a war of position, fighting to come out on top in the genre and gain social prestige. They left behind those names that nicknamed them

Next page