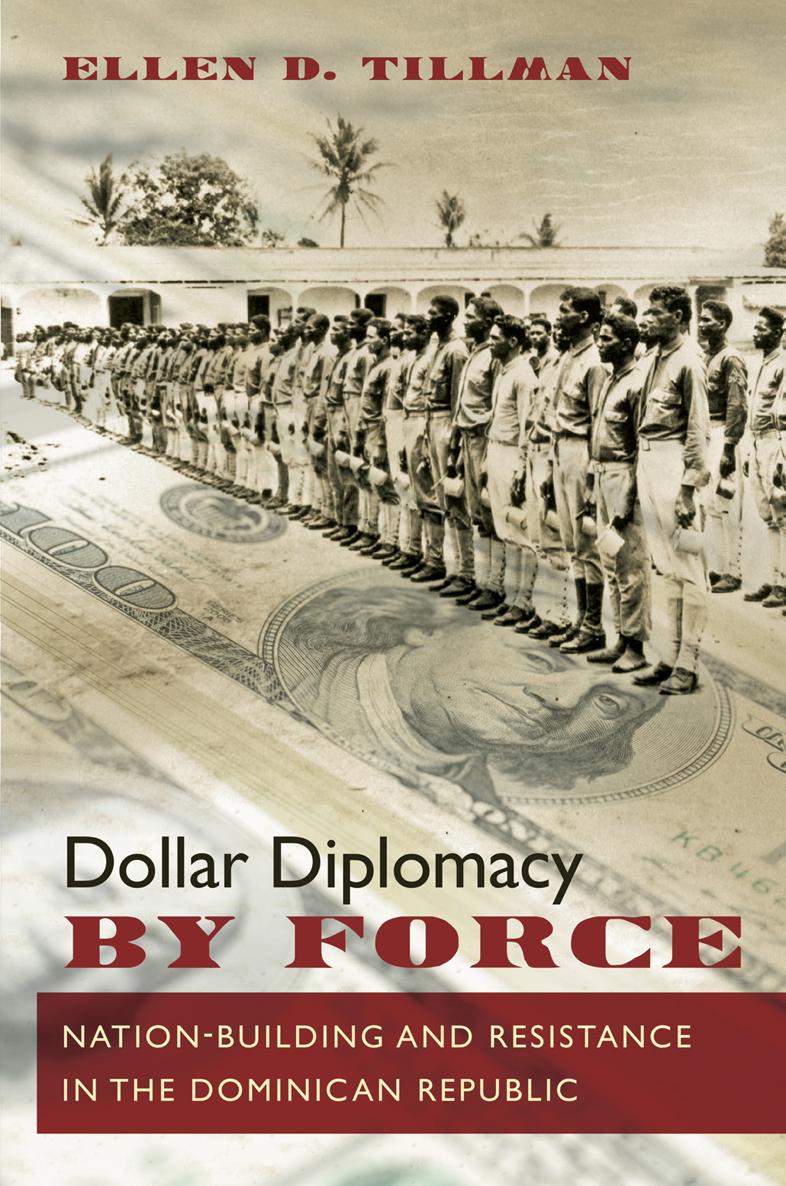

Dollar Diplomacy by Force

This book was published with the assistance of the Thornton H. Brooks Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2016 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Set in Espinosa Nova by Westchester Publishing Services

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Cover illustrations: banknotes, Ingram Image Ltd.; formation of the Guardia Nacional Dominicana, Official Marine Corps Photo.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tillman, Ellen D., author.

Dollar diplomacy by force : nation-building and resistance in the Dominican Republic / Ellen D. Tillman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2695-6 (pbk : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4696-2696-3 (ebook)

1. Dominican RepublicHistoryAmerican occupation, 19161924. 2. Military occupationSocial aspectsDominican Republic. 3. Dominican RepublicPolitics and government18441930. 4. Dominican RepublicForeign relationsUnited States. 5. United StatesForeign relationsDominican Republic. I. Title.

F1938.45.T55 2016 972.93052dc23

2015031898

Portions of this work appeared previously in somewhat different form in Ellen D. Tillman, Militarizing Dollar Diplomacy in the Early Twentieth-Century Dominican Republic: Centralization and Resistance, Hispanic American Historical Review 95, no. 2 (2015): 26997. 2015 Duke University Press. All rights reserved. Republished by permission of the publisher.

Contents

Markets, Militaries, and Modernization

U.S.Dominican Relations to 1899

Military Diplomats and Dollar Diplomacy

From Customs Receivership to Civil War

Involvement to Invasion

Military Control and the Defense of Local Sovereignty

A Promiscuous Heaping of Adventurers

The Constabulary Experiment of 19161918

Regional Negotiation and Resistance

The Moralizing versus the Expedient

Opposing Networks for Change

Consolidating Reform and Resistance after 1920

Products of Compromise

Legitimating State and Military

Acknowledgments

I am greatly indebted to the following for their help through the years of research that brought this work together and wish to extend my appreciation here. To my dissertation advising committee at the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana: Nils P. Jacobsen, John A. Lynn, and Kristin Hoganson, without whom I would have been quite lost, and to Michel Gobat of the University of Iowa. I would also like to thank Marcelo Bucheli and Jose Cheibub for their advice and guidance, which helped me to locate my study in the international economy and politics of the time. Special thanks go to my other long-term advisers for all their help over the years: Joseph Love of University of Illinois and Kevin C. Murphy of the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia; my work is very much a product of the counsel and wisdom of those outside of my committee who guided me along the way and opened my eyes to new ways of envisioning history. My gratitude, also, to Bruce Calder of the University of Illinois-Chicago for his advice during my research, and for the extensive and generous help of Brandon Proia and the editorial staff at University of North Carolina Press, as well as to the anonymous reviewers who provided advice during the revision process.

For monetary support for my research I am indebted primarily to the History Department at the University of Illinois and to the University of Illinois Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studieswhich funded the graduate research that began this projectas well as to the Foreign Language Area Studies Fellowship (FLAS) at the University of Illinois. For other aid that made this work possible, my sincere and lasting thanks to the Society for Military History (SMH), the United States Commission on Military History (USCMH), the International Commission on Military History (ICMH), and Michael Gray.

For lodging during my studies, I extend my thanks to Lucina de la Cruz and her family for their gracious hospitality and friendship, and to Teresa Gray (TAG) and her daughters for keeping me while I was researching at Quantico. For their general support, advice, and availability throughout the years of my research, I would also like to thank Luis B. Peralta and his family; Lic. Eligio Serrano Garca (Gabriel), Charles Neimeyer, and the staff at the Quantico USMC Historical Division and the Marine Corps archives and special collections; Christine Kern, the staff at the Biblioteca Pblica de Santiago, the staff of the Archivo General de la Nacin in Santo Domingo, and the archivists at NARA in College Park, Marylandall of whom were more than willing to go out of the way to help me out.

Finally, my extensive appreciation always to Kitty and Joseph Davies for making it possible, and to Jasmine and Ticonderoga for putting up with it for so long.

Dollar Diplomacy by Force

Introduction

In May of 1916, U.S. marines occupied Santo Domingo, the capital city of the Dominican Republic. Their stated pretext was the Dominican governments repeated failure to uphold a customs agreement signed with the United States in 1907. In the midst of political confusion surrounding the invasion, as the Dominican provisional government refused to relinquish control of its military, U.S. marines began to occupy the country. The original idea of the policy of dollar diplomacy, as expressed by both Theodore Roosevelts and William Howard Tafts administrations, had been to replace dollars for bullets, as Taft was to put itto guarantee economic and political stability in the Caribbean region without the need for intrusive, and by 1905 highly controversial, military interventions. Yet the result was the exact opposite: on 29 November, U.S. Navy Captain Harry S. Knapp read his formal proclamation for U.S. military occupation of the Dominican Republic.

A new military government wielded power. Its first measures sought to bring order through the exertion of military control and included the disbanding of all Dominican armed and police forces, the disarmament of the population, and strict censorship of the press. As World War I concerns diverted the U.S. governments attention toward the wider Atlantic and Europe, it left the occupations administration for years under control of the U.S. Navy and marines. Officers expected to improve Dominican society by building infrastructure and creating a new Dominican army modeled on the U.S. Marine Corps, but also planned in terms of larger strategic interests. Connected as it was to Washington-based foreign policies, the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic from 1916 to 1924 was, at its core, a military experiment.

The Dominican experiment in dollar diplomacy also became an experiment, in the final accounting, in military exportation of U.S.-style government institutions. It was unique among contemporary U.S. occupations in the ways that U.S. government decisions made amid the lack of a treaty gave unprecedented and unequaled command of internal occupation decisions to the U.S. Navy Department during the height of direct U.S. influence. U.S. officers were well aware of this as they pushed for increased control, and, especially from the onset of full military occupation in 1916, many saw this occupation as a unique opportunity to demonstrate two major points. The first was that U.S. systems of government, military, and social order could be exported; the second was that the military was the most logical organization to export them. From the 19057 creation of a U.S. customs receivership to the subsequent military interventions and through the 191624 outright military occupation of the country, for many the Dominican experiment became a laboratory and showcase for the benefits of U.S. society, identity, whiteness, and professionalization.