Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.anthempress.com

This edition first published in UK and USA 2022

by ANTHEM PRESS

7576 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

Copyright Eve Hayes de Kalaf 2022

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021948272

ISBN-13: 978-1-78527-764-1 (Hbk)

ISBN-10: 1-78527-764-2 (Hbk)

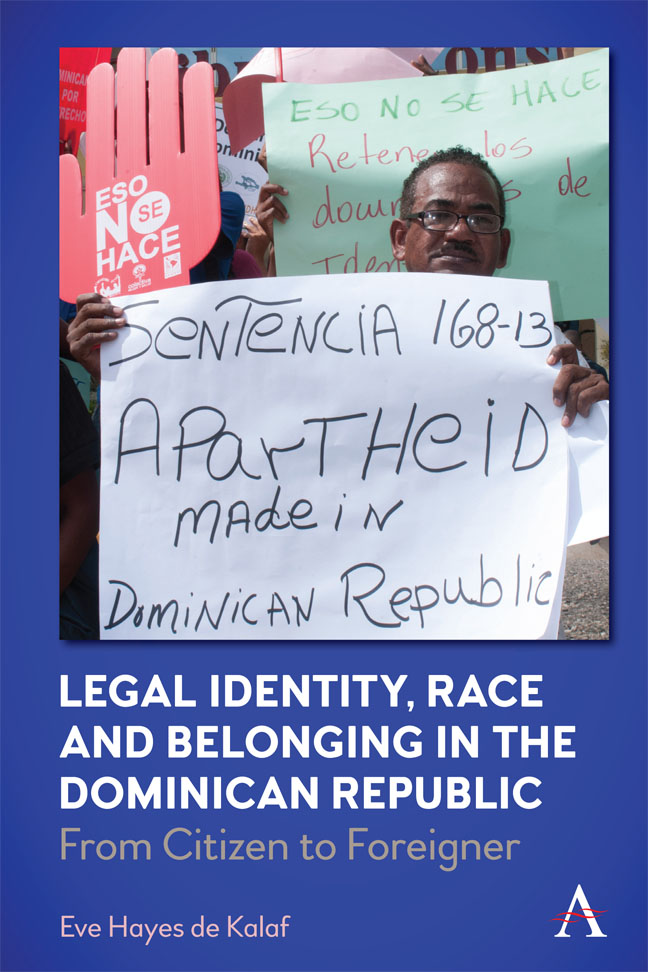

The cover photo was taken by Lorena Espinoza Pea featuring the Dominican anthropologist Juan Rodrguez Acosta.

This title is also available as an e-book.

This book offers some uncomfortable insights into the use and abuse of modern-day identity-based development solutions for exclusionary and citizenship-stripping practices. It is the culmination of a long personal, intellectual and transformative journey that began in the Dominican Republic and has taken me around the world. Born from a desire and dedication to amplify the lived experiences of everyday Dominicans, this book includes the often overlooked, ignored or forgotten voices in contemporary debates about statelessness, citizenship, legal and, increasingly, digital identity.

This book is a cautionary tale regarding the rapid expansion of global identification measures which aim to provide universal legal identity in the run-up to the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study is the first to link the promulgation of contemporary ID practices by international organisations, such as the World Bank, the United Nations (UN) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), with practices implemented by the Dominican state to arbitrarily and retroactively strip citizenship from native-born Black citizens of (largely) Haitian ancestry.

I show that while identification programmes, and the digital technologies that support them, strive to include marginalised populations, they also have the potential to exclude some users from these systems. I use policy analysis, archival research and semi-structured interviews to illustrate how citizens have been forced to navigate complex bureaucratic systems and overcome seemingly unsurmountable hurdles, in order to retain or gain access to their Dominican legal identity.

The island of Hispaniola is shared between the Dominican Republic (to the east) and Haiti (to the west). For over eighty years, the Dominican Constitution recognised the right of all people born on Dominican territory to jus soli This included persons who not only already identified as Dominican citizens but also had the paperwork to prove it.

As we will see in this book, tens of thousands of persons of Haitian ancestry found themselves in a fierce battle to (re)obtain their legal identity when the authorities began to reject their requests for paperwork on the grounds that their parents were born in transit or residing illegally. The Sentencia centred on Juliana Deguis Pierre, a documented woman of Haitian ancestry. Civil registry officials were refusing to renew her birth certificate, which she needed to acquire a national identity card. Sentencia judges decided that the irregular migratory status of Deguis Pierres parents at the time of her birth exempted their daughter from Dominican citizenship. As a result, they determined she had retrospectively inherited the illegal status of her parents and subsequently invalidated her birth documentation. Deguis Pierre, they decided, was not, nor could she ever have been, a Dominican citizen. She was rendered stateless by this decision.

In an attempt to diffuse tensions, and in response to strong international indignation to the ruling, the former Dominican president Leonel Antonio Fernndez Reyna claimed the Sentencia was necessary as it would help rectify anomalies within the civil registry, some dating back over eighty years. He lamented that, in his opinion, there were still people living in the country who, like Deguis Pierre, had wrongly received their legal identity documentation, thus leading them to assume that they were Dominican citizens. He stated:

If [the Sentencia] is retroactive then there has been a problem determining the legal status of people living in the country. They have been under the impression they are Dominican and, at some point, were even in possession of [Dominican] paperwork. Something like that can lead to other types of problems.

I was in a unique and privileged position to carry out the research for this book. I am a dual British-Dominican national having naturalised as a Dominican citizen after several years living and working in the Caribbean. Thanks to my national identity card (cdula de identidad y electoral), I had voted in the national elections, owned a credit card, held a local drivers licence and travelled on my Dominican passport. When news of the Sentencia broke in 2013, I found it inconceivable that I a white, foreign-born European woman would continue to benefit from my status as a Dominican when hundreds of thousands of Black Dominicans born in the country abruptly found themselves stripped of their nationality. The sense of injustice at the decision was palpable and the main motivation for me writing this book.

During the time I lived on the island, I had seen just how overwhelmingly cumbersome and seemingly Kafkaesque registrations could be. Many Dominicans call the civil registry el tollo, which literally translates as atolladero, meaning mess. For many, their interactions with the civil registry were often painstakingly bureaucratic and frustrating. I had experienced first-hand how my foreign birthplace, race and social status placed me in position of privilege above native-born Black Dominicans, Haitian migrants and Haitian-descended groups. Disgracefully, I was regularly allowed to skip queues at government offices and given priority over others, many of whom had to wait for several hours to be seen by a state official.

A number of years ago, I attempted to cross the Dominican-Haitian border on a public bus. Immigration officials stopped me, stating they were suspicious as to why I was travelling on a Dominican passport. I was detained, taken to a back office and interrogated as to whether I was a dominicana neta (a real Dominican). It was only years later that I came to realise I was not stopped and questioned solely because the documents I was carrying aroused suspicion. My interaction with the border officials depended on a variety of social factors, including the situation in which they were presented, the audience ). My experience was intrinsically linked not only to how my papers identified me but also to how I was perceived in my interactions with others.