Table of Contents

For Bobbie Richardswithout whose unstinting support,

over many years, nothing would ever be written

PRAISE FOR ALISTAIR HORNE AND La Belle France

How much happier life would be if one could read books as riveting as Alistair Hornes... every week of the year. Horne has a masterful way of infusing grand historical themes with rich narrative detail.

Francine du Plessix Gray

Horne [is] one of the most graceful and satisfying of historians.

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

The writing is sharp, the pace terrific and hardly a page turns without leaving a memorable detail or telling phrase to savour. Horne in top form is not to be missed. A full-throated wonderfully readable chronicle.

The Independent (London)

A fluid, graceful, deliberate prose stylist.... Hornes purpose is not to be encyclopedic but to paint a portrait, and this he does surpassingly well.

The Washington Post Book World

This is the history of France one has always wantederudite, affectionate, vastly entertaining and carried along with Tolstoyan sweep as all the characters leap to life.

The Daily Telegraph (London)

Horne [possesses] broad erudition and [an] intense feel for French history.

The Washington Times

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

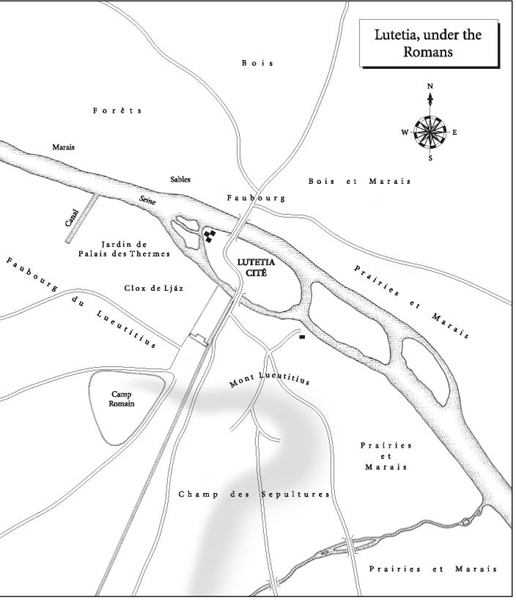

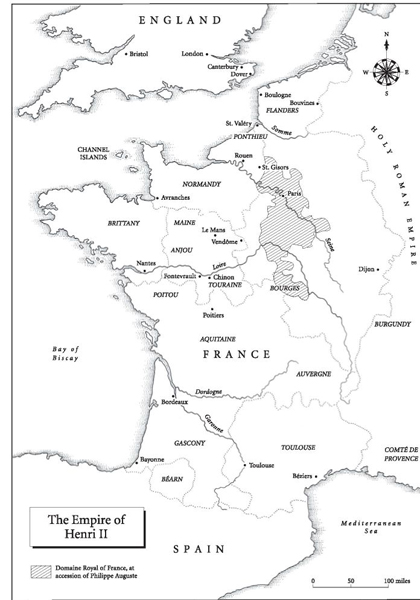

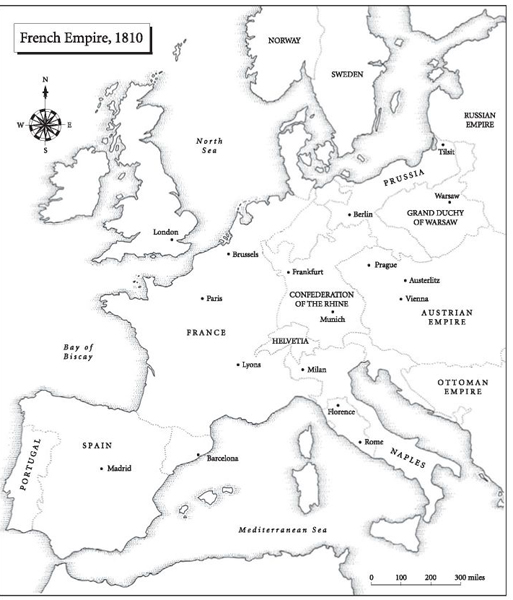

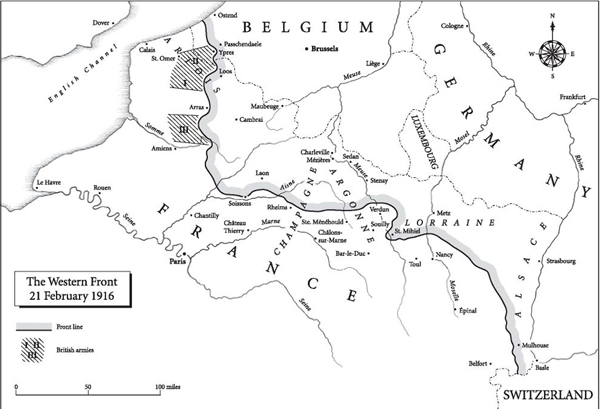

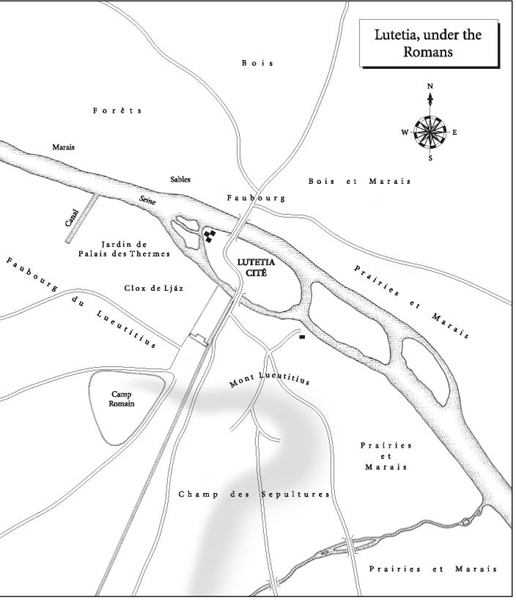

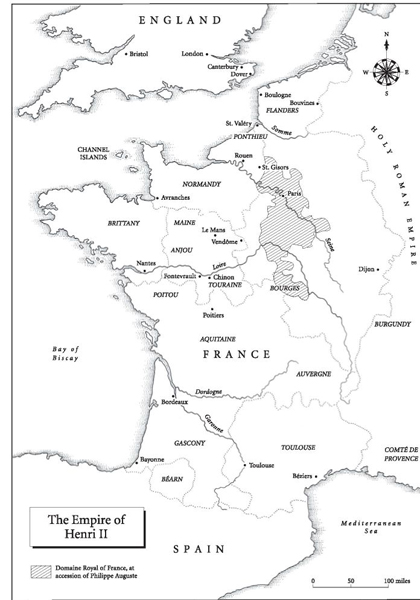

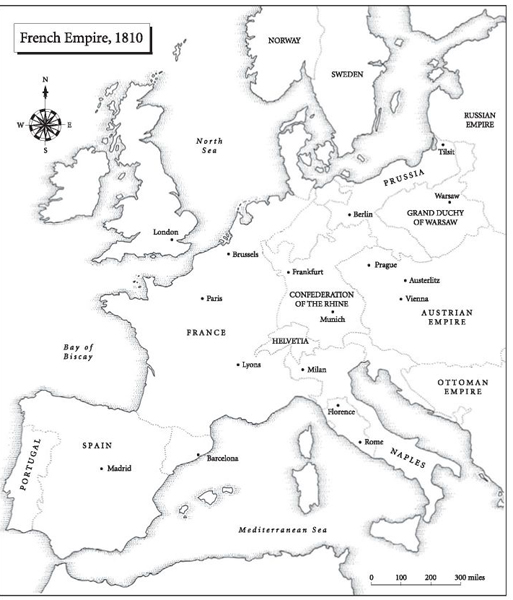

THIS JOURNEY through two thousand years of French history represents, for me, the culmination of some four decades of a love affair with France, of studyand of enjoyment. In the first instance I owe an unquantifiable debt of gratitude to France herself, and to very many French people. In particular I would just like to repeat once again my thanks to all, in both Britain and France, who are listed in my recent sister work of Seven Ages of Paris. Without their continuing support I could never have persisted with the present work. In addition, I am especially beholden to Ash Green, and my publishers, Knopf, of New York, for their outstanding marketing success of Seven Ages in the US, and also to Macmillan, London, for kind permission to use sections of their edition of Seven Ages; and to them in addition as publisher of no less than eight of my titles on French history, over a period of more than forty years. On all of these (listed among the bibliography) I have been able to draw for the present work. As the great English historian Namier Lewis once acidly remarked: History doesnt repeat itselfonly historians repeat each other. But we do try hard not to repeat ourselves too often. In this context, I am above all indebted to my editor at Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Ion Trewin, and his assistant editor, Anna Herv and, for his dedicated long hours of work in cutting, polishing and serving up a thoroughly messy MS, to Jon Jackson. A vast work was also done on collating and selecting from a whole museum-load of pictures by Tom Graves of Weidenfeld & Nicolson, and thanks to John Gilkes for his work on the maps. Much meticulous work was put in at proof stage by Ilsa Yardley and Chris Bessant. To all I remain deeply beholden.

and, for his dedicated long hours of work in cutting, polishing and serving up a thoroughly messy MS, to Jon Jackson. A vast work was also done on collating and selecting from a whole museum-load of pictures by Tom Graves of Weidenfeld & Nicolson, and thanks to John Gilkes for his work on the maps. Much meticulous work was put in at proof stage by Ilsa Yardley and Chris Bessant. To all I remain deeply beholden.

I had the great good fortune to be able to persuade my old friend, Professor Douglas Johnsonone of the English-speaking worlds most distinguished historians of Franceto read through what I have written and check for howlers. At various stages in the work he gave me invaluable help and encouragement; as did (once more) that stalwart defender of the langue franaise, Maurice Druon, KBE, of the Acadmie Franaise. It goes without saying that any surviving solecisms, or repetitions, have to be the fault of the jaded author alone.

Once again, Janet Robjohn slaved uncomplainingly on research, filing and secretarial work; while Douglas Matthews coped nobly with a complicated index.

For help on contemporary cultural themes, I am beholden to Monsieur Olivier Chambard, Cultural Attach in the French Embassy, London; and, lastly, I owe a special and most agreeable debt to Frances much-loved ambassadorial team in London, Grard and Virginie Errra.

Finally, I cannot go without mentioning once again my old college at Cambridge, Jesus, for providing occasional solace and facilities for research at the University Library, far beyond the due of a Hon. Fellowand, again, that willing and most long-suffering treasury, indispensable to all historians, the London Library.

INTRODUCTION

EVER SINCE, back in the 1960s, I wrote the Price of Glory trilogy about Franco-German wars, I have been enticed by the dangerously ambitious project of attempting a full-scale History of that complex, sometimes exasperating, but always fascinating country France. At last, the year 2004 provided a kind of launching pad. It was the hundredth anniversary of the signature of the Entente Cordiale, the Treaty which ended centuries of war and enmity between Britain and her neighbour. Friend or Foe? Over the centuries more often the latter than the former. (2004 also happened to be the bicentenary of the Coronation as Emperor of Britains deadly enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte; he who came within several inches that same year of repeating the success of William the Conqueror, failing where a later despot, Adolf Hitler, also failed.)

The Entente Cordiale conveys rather different things in British and American historyand for France. For France it meant, quite simply, the certainty at last of an ally who would counter-balance the dread power of Kaiser Wilhelm IIs vast and menacing Reich on her doorstep; and regain the lost provinces of Alsace-Lorraine so brutally torn from her thirty-three years previously. At terrible, unacceptable cost for France, it would bring victory in 1918, but predictable defeat in 1940.

For Britain the Entente, if it signified the end of all those centuries of conflict with France, it also meant inevitable involvement in a major European war, for the first time since 1815and against a new enemy. (There are today, however, still a revisionist minority of British scholars who think that maybe the Entente was a thoroughly bad thing for Britain, and that somehow we should have kept out, and made friends with the Kaiser with his glaring eyes and aggressive moustaches, and hang-ups derived from that shrivelled arm.)

For the USA, the Entente, which was still to leave an unbalanced alliance not sufficiently powerful enough to defeat Germany by itself in 191417, would make inevitable involvement in two world wars, and (to date) a permanent departure from the exhortations of Washingtons Farewell Address. So, inescapably, perceptions of French history and its message differ radically from one side of the Atlantic to the other.

Next page

and, for his dedicated long hours of work in cutting, polishing and serving up a thoroughly messy MS, to Jon Jackson. A vast work was also done on collating and selecting from a whole museum-load of pictures by Tom Graves of Weidenfeld & Nicolson, and thanks to John Gilkes for his work on the maps. Much meticulous work was put in at proof stage by Ilsa Yardley and Chris Bessant. To all I remain deeply beholden.

and, for his dedicated long hours of work in cutting, polishing and serving up a thoroughly messy MS, to Jon Jackson. A vast work was also done on collating and selecting from a whole museum-load of pictures by Tom Graves of Weidenfeld & Nicolson, and thanks to John Gilkes for his work on the maps. Much meticulous work was put in at proof stage by Ilsa Yardley and Chris Bessant. To all I remain deeply beholden.