THE ANCIENT GREEKS defined hubris as the worst sin a leader, or a nation, could commit. It was the attitude of supreme arrogance, in which mortals in their folly would set themselves up against the gods. Its consequences were invariably severe. The Greeks also had a word for what usually followed hubris. That was called peripeteia, meaning a dramatic reversal of fortune. In practice, it signified a falling from the grace of a great height to unimaginable depths. Disaster would often embrace not only the offender, but also his nearest and dearest, and all those responsible to him.

Having written, over the course of fifty-odd years, numerous books and articles on warfare in its various shapes, I sat down some time ago to reflect on what might be its common features that stand out over the ages. One that emerged preeminently was hubris: wars have generally been won or lost through excessive hubris on one side or the other. In modern military parlance it might also be dubbed overreach. So this is the genesis of the current work. Wars and battles seldom happen in isolation, in a vacuum. Each has its causes from the past, and each has its often baneful consequences in a subsequent period. To study them, the good historian needs to be able to scan backward and forward, as well as sideways. Thus I have focused on those conflicts that affected future history powerfully in ways that transcended the actual war in which the conflict was set.

I chose to limit my study to the first half of the twentieth century, the bloodiest century in history, and a century that indeed could be called the century of hubrisduring which humans were slaughtered in numbers to exceed those of any other century, all at the whim of one or two warlords or dictators.

One immediate effect of hubris is often complacency, a first step on the path to ruin. As the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck once remarked, in an axiom that might be seen as a prediction of the eventual fate of his own country, A generation that deals out a thrashing is usually followed by one which receives it.

Two battles that I have already written about, the German Siege of Paris (18701) and the gory Battle of Verdun in World War I (1916), provide good examples of the validity of Bismarcks warning. Out of their victory in 1871, the Germans emerged so well stuffed with arrogance that defeat in the next war, if not the one after, was all but certain. Nearly a half century later, the French heirs to the terrible pyrrhic victory of Verdun on the one hand felt that they could never repeat such a sacrifice and, on the other, were impregnated with the hubristic self-confidence that they would be safe behind the super-Verdun-like fortress of the Maginot Line, and that the hereditary German foe ne passera pas (shall not pass). The shibboleth of their fathers heroism was enough. Or was it? Six weeks in the summer of 1940 would prove that it was not.

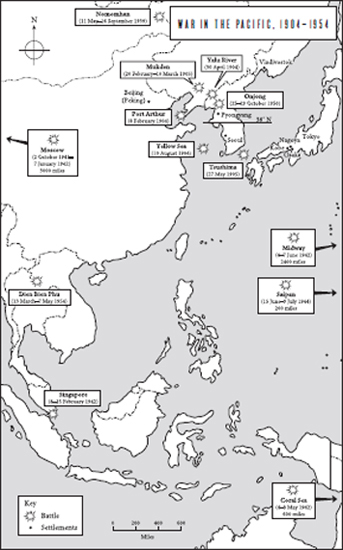

This book is divided into five parts. I begin with the 1905 Battle of Tsushima, and the Japanese sinking of the Russian fleet at Port Arthuran event that shocked the world. Bracketed within that is a look at the triumph of Japanese ambitions. In the second part, the little-known Battle of Nomonhan in Mongolia in 1939 illustrates the rise of Soviet power and the first check on Japan. Third, after Hitler had overreached himself with his invasion of the Soviet Union, there is the Battle of Moscow in 1941, which takes us to Pearl Harbor and to the fourth part, the turning point of the Pacific War with the Battle of Midway. Key episodes from the Korean War, in part 5, provide a perfect illustration of the hubristic folly of not knowing when to stop. I end with the French disaster in Vietnam at Dien Bien Phu, the last of the old-fashioned colonial wars in the Far East.

My choice of subjects may well be challenged as capricious: it is certainly idiosyncratic and personal. Deliberately, the First World War is left out. It seemed to me that the whole war began, and was caused by, various sublime practitioners of hubris in conflict with one another. Further, it would be difficult to identify any one battle that held calamitous consequences for the future. The whole war did that.

I would hesitate to write anything to belittle British prowess in either world war. But where was the battle in which hubris displayed by the leadership affected postwar events? El Alamein? Caen? Arnhem? Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery was certainly a candidate for hubris in the eyes of his allies. But, as I tried to show in my biography The Lonely Leader, Montgomery had his special reasons. He inherited a battered army that had been defeated almost incessantly since the beginning of the war and was justifiably alarmed by the Wehrmacht; in consequence, he had to infuse it with large doses of what he called Bingethe right spirit for victory. Then again, without belittling British arms, the Battle of El Alamein, designated by Churchill as the end of the beginning, was indeed a small affair compared numerically with the troops arrayed before Moscow in 1941over ten to one in comparison with El Alameinand could there be found in any of Montys battles issues that would affect postwar history?

To my mind, the Battle of Moscow was more definitively an end of the beginning, and probably more than any other salient victory, it was to have an influence on Soviet conduct in postwar events. Even today, the scale of the fighting and the numbers before Moscow in 1941 stun the imagination. Seen from this distance, it was a true turning point in the war, more significant even than Soviet marshal Georgy Zhukovs great victory the following year at Stalingrad. It marked a decisive moment in warfare, as the first time that the apparently invincible Panzers were stopped, defeated, and then forced to retreat. It also marked Hitlers final loss of belief in his generals, displaced by his belief in his own starwith the disastrous consequences that remain familiar to history. More than that, the victory, and its cost to the Russian people, established in Stalins mind the shape of the postwar map of Europe under a Soviet aegis. More immediately, it confirmed him as the irreplaceable, omnipotent Russian war leader. As far as overall Allied strategies were concerned, so much after Moscow seems to have been dancing to Stalins tune. Certainly, for the next unhappy forty-five years, the shape of Europe would be the shape that Stalin had dictated.