ALISTAIR HORNE was educated in Switzerland, at Millbrook School, New York, and at Jesus College, Cambridge, where he played international ice hockey. In World War II, initially a volunteer in the RAF, he served with the Coldstream Guards between 1944 and 1947, ending as a captain attached to MI5 in the Middle East. In the 1950s he was a foreign correspondent for the Daily Telegraph until taking up a fulltime writing career in 1955.

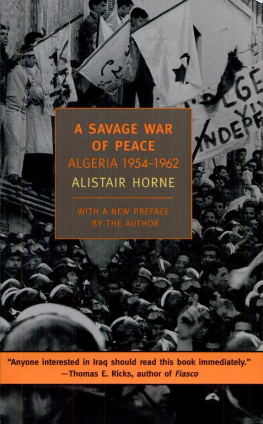

Horne's trilogy of Franco-German conflict comprises The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune, 187071, The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916, and To Lose a Battle: France 1940. In 1963, The Price of Glory was awarded the prestigious Hawthornden Prize; when first published in 1977, A Savage War of Peace won both the Yorkshire Post Book of the Year Prize and the Wolfson Literary Award. Other books include The Lonely Leader, a biography of Field Marshal Montgomery; Small Earthquake in Chile; and, most recently, Seven Ages of Paris, La Belle France: A Short History, and The Age of Napoleon.

In 1969 Horne founded the Alistair Horne Research Fellow-ship for young historians at St. Antony's College, Oxford. In 1993 he was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor, and in 2003 he was knighted for his work in French history.

Alistair Horne is a specialist on Anglo-American relations, to which his autobiographic A Bundle from Britain belongs. He is currently working on an authorized biography of Henry Kissinger in 1973 and a second volume of memoirs.

A SAVAGE WAR OF PEACE

Algeria 19541962

ALISTAIR HORNE

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

To

A.D.M. and C.D.H.

the only begetters

Take up the White Man's Burden

The Savage wars of peace

Fill the mouth full of famine

And bid the sickness cease.

Rudyard Kipling

CONTENTS

PART ONE

Prelude 18301954

PART TWO

The War 19541958

PART THREE

The Hardest of All Victories 19581962

Illustrations

6 .

17., 18

29.32.

Preface to the 1977 edition

I intend to write the history of a memorable revolution which pro-foundly disturbed men, and which still divides them today. I do not conceal from myself the difficulties of the enterprisewhereas we have the advantage of having heard and observed these old men who, still full of their memories, and still aroused by their impressions, reveal to us the spirit and the character of the causes, and teach us to understand them. The moment when the actors are about to expire is perhaps the suitable one to write history: one can glean their evidence without sharing all their passionsI have pitied the combatants, and I have freely applauded the generous spirits.

Adolphe Thiers, preface to Histoire de la Rvolution Franaise, 1838

I N January 1960 I was in Paris, researching into World War I, when Barricades Week broke out in Algiers. The European settlers, or pieds noirs, were in revolt against de Gaulle and the elite paras were openly siding with them. For the first time the press began using the ugly word insurgents, menacingly evocative of Franco and the Spanish Civil War. Momentarily it looked as if the still-fragile structure of de Gaulles Fifth Republic might crack. Then de Gaulle delivered one of his magical appeals, and the crisis dissolved like a puff of smoke. What most vividly remains in my mind of that tense week in Paris was the passionate involvement of members of the foreign press; beyond the excitement of events and professional detachment they agonised at Frances dilemma and, during de Gaulles television appearance, tears of emotion were brought to more than one otherwise steely eye. The history of France, a permanent miracle, says Andr Maurois at the end of his Histoire de la France, has the singular privilege of impassioning the peoples of the earth to the point where they all take part in French quarrels. This is true. Writing about the history of France has the elements of a love affair with an irresistible woman; inspiring in her beauty, often agonising and maddening, but always exciting, and from whom one escapes only to return again. After nearly ten years spent on writing about Franco-German conflicts I felt instinctively that, sooner or later, I would be lured back to take part in this latest drama of French history, in one form or another, once the dust had sufficiently settled. It took my publishers to propose the idea.

I also happened to be in France on two other occasions when events in Algeria threatened the very existence of the Republicin May 1958 and again in April 1961, the latter the most dangerous of all when ancient Sherman tanks were rolled out on to the Concorde to guard against a possible airborne coup mounted from Algiers. Each episode seemed to me, in retrospect, to bear a curious resemblance to the essential rhythm of other great crises in modern French history, whether in 1789, 1870, 1916 or even 1940: a headlong rush to the brink of disaster, or even beyond it, followed by an astounding recovery and eventually leading to a re-flowering of the creative energies and brilliance that are France. The war in Algeria (which lasted nearly eight yearsalmost twice as long as the Great War of 191418) toppled six French prime ministers and the Fourth Republic itself. It came close to bringing down General de Gaulle and his Fifth Republic and confronted metropolitan France with the threat of civil war. Yet, when defeat led to the cession of this corner-stone of her empire where she had been chez elle for 132 years, out of it arose an incomparably greater France than the world had seen for many a generation.

What in France is called la guerre dAlgrie and in Algeria the Revolution was one of the last and most historically important of the grand-style colonial wars, in the strictest sense of the words. Many a French leader, and especially the pieds noirs of Algeria, waged the war in the good faith that they were, indeed, shouldering the White Mans Burden. Many a French para gave his life heroically, assured that he was defending a bastion of Western civilisation, and the bogey slogan of the Soviet fleet at Mers-el-Kbir retained its force right until the last days of the prsence franaise. It was a war of peace in that no declaration of hostilities was ever made (unless one should recognise the first FLN proclamation of 1 November 1954 as such), and during most of the eight years the vast majority of Frenchmen lived unaffected by it. Equally, it was undeniably and horribly savage, bringing death to an estimated one million Muslim Algerians and the expulsion from their homes of approximately the same number of European settlers. If the one side practised unspeakable mutilations, the other tortured and, once it took hold, there seemed no halting the pitiless spread of violence. As at a certain moment in the Battle of Verdun in 1916, it seemed as if events had escaped all human control; often, in Algeria, the essential tragedy was heightened by the feeling thatwith a little more magnanimity, a little more trust, moderation and compassionthe worst might have been avoided.

Next page