New Degree Press

Copyright 2021 Andrew G. Farrand

All rightsreserved.

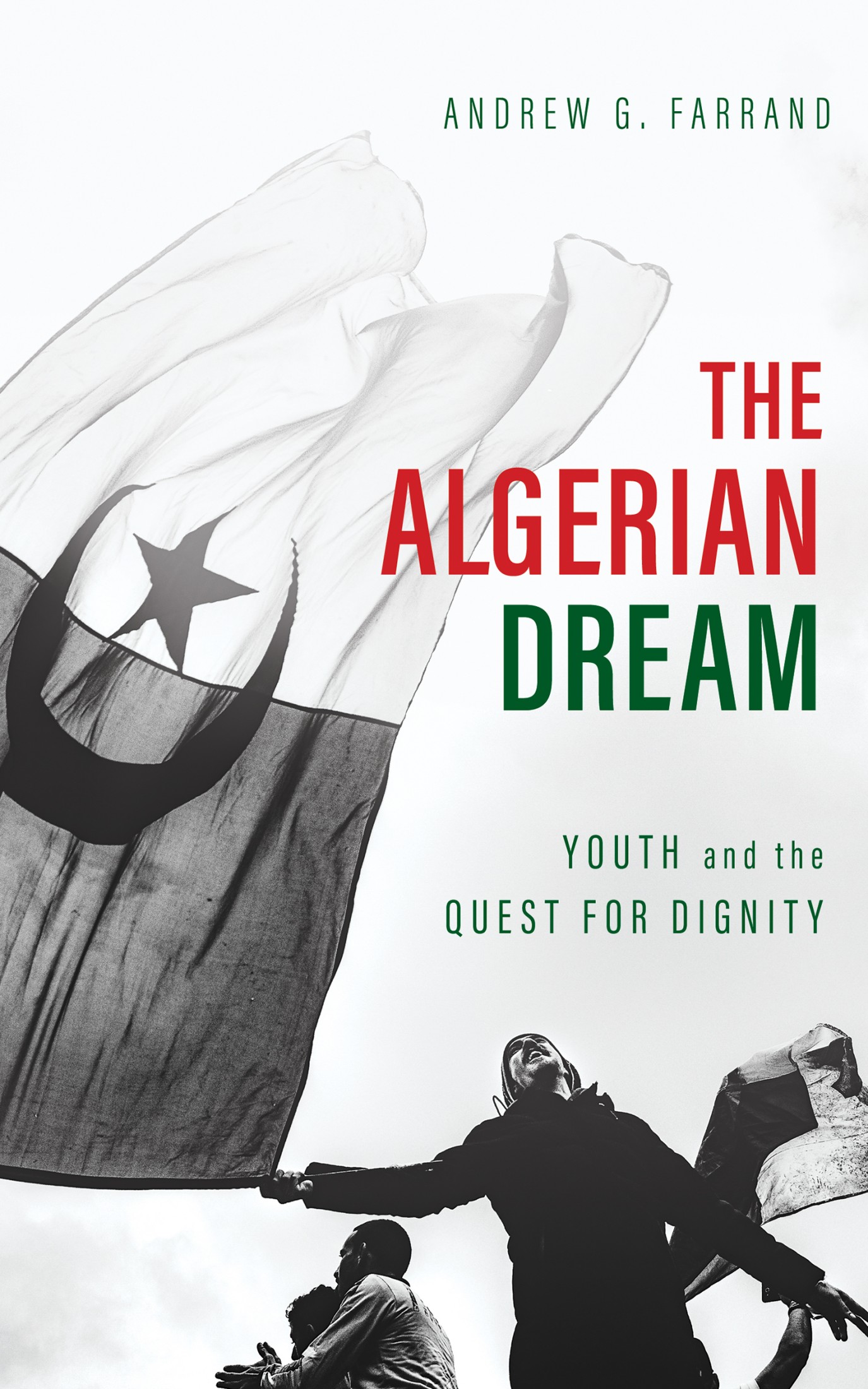

Front and back cover photographs copyright SabriBenalycherif.

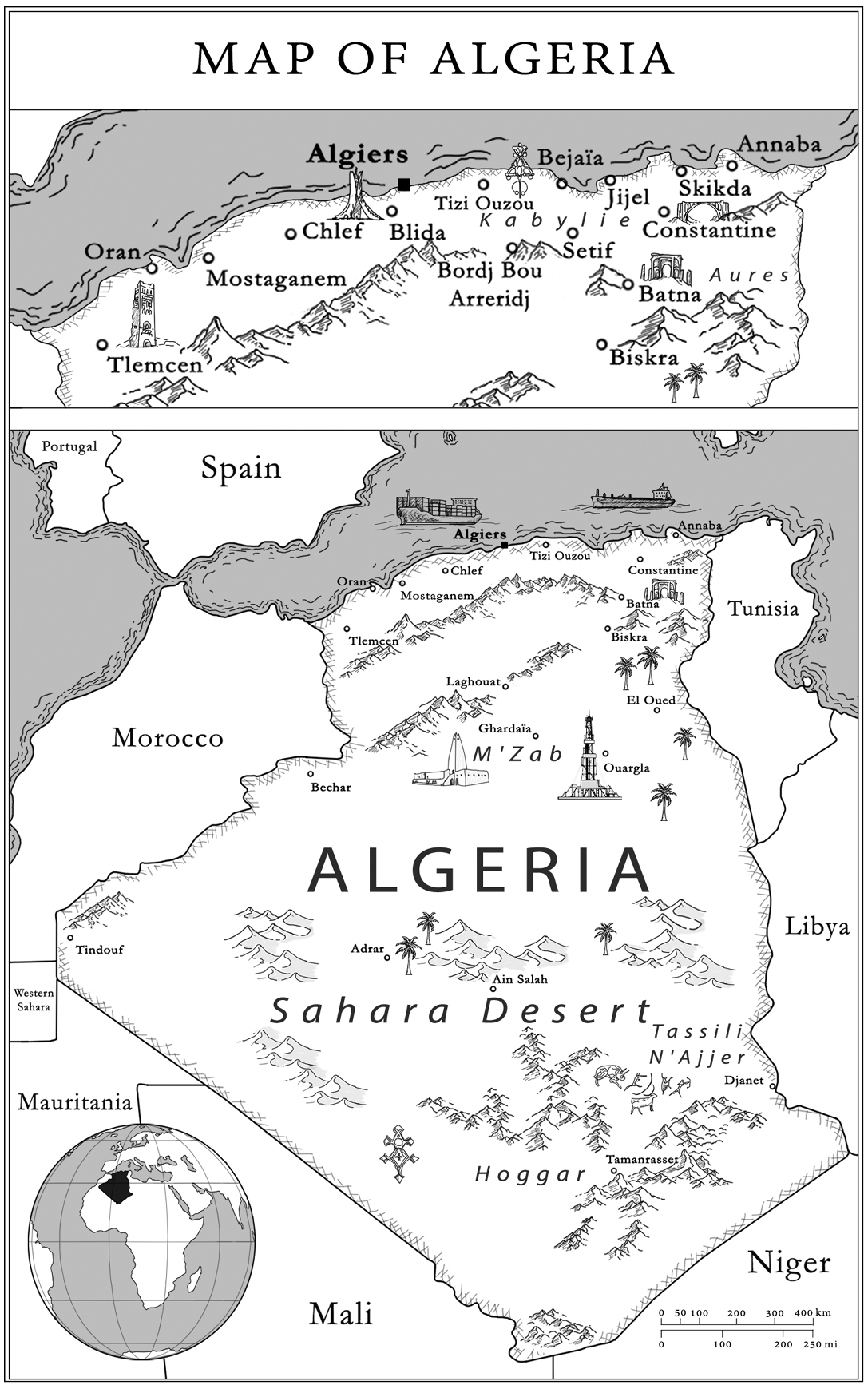

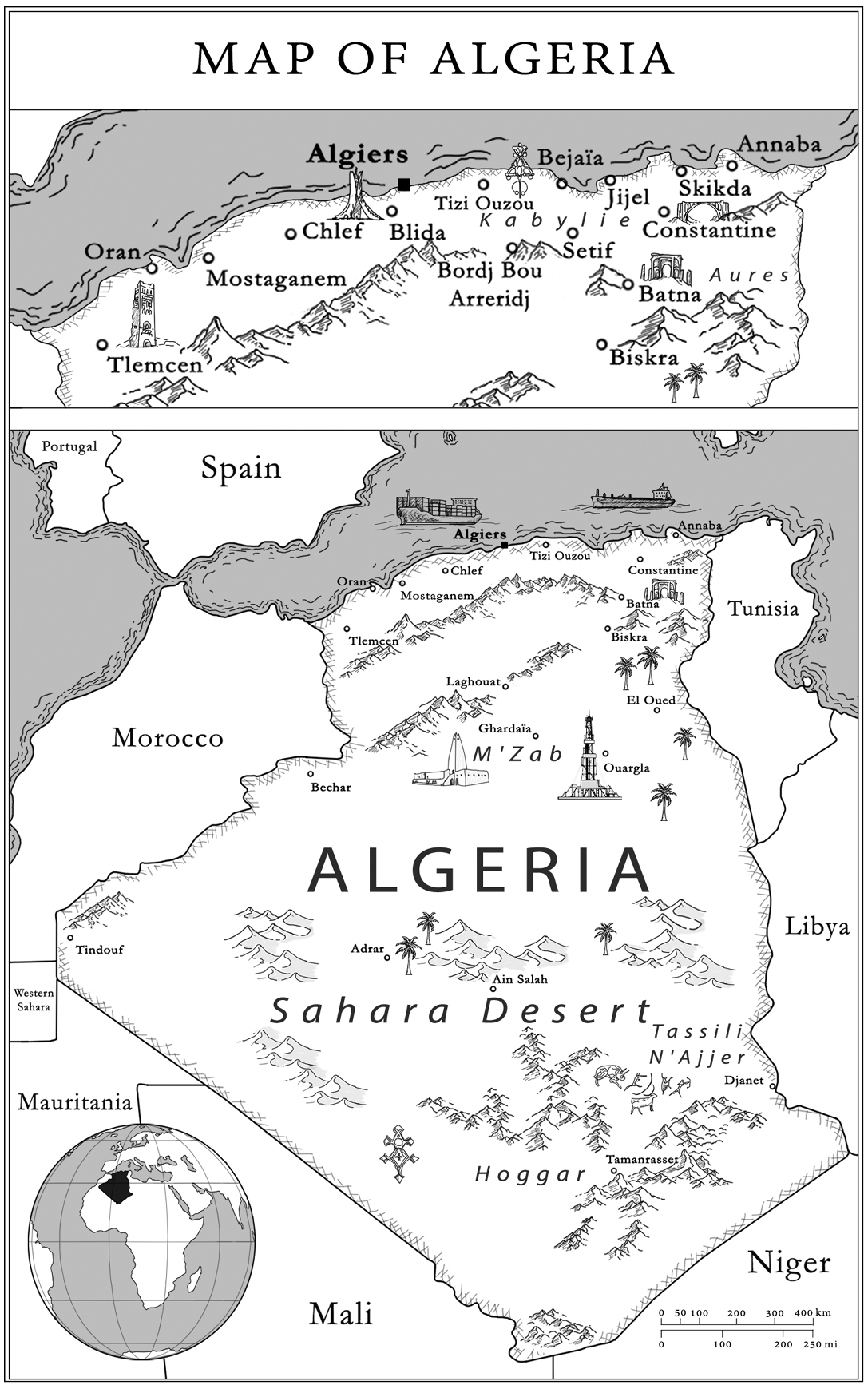

Map of Algeria copyright Amina WafaaBerrais.

Interior photographs copyright Andrew G. Farrand.

The Algerian Dream

Youth and the Quest for Dignity

ISBN 978-1-63676-716-1 Paperback

ISBN 978-1-63730-051-0 Kindle Ebook

ISBN 978-1-63730-153-1 Ebook

For Nina

Contents

Disclaimer

Wherever possible, events presented in this book are based on verifiable written sources, as documented in the reference notes. Personal anecdotes are reconstructed as faithfully as possible based upon memory, personal notes, and follow-up interviews when needed.

Names of some individuals cited in the text have been changed to protect their identities.

The contents of this book are those of the author alone and do not reflect the position or viewpoints of any of the individuals or organizations mentioned therein.

Note on Transliteration of Arabic and Tamazight Terms

The orthography of Arabic and Tamazight (Berber) words in Roman characters found in this book may appear unfamiliar to some readers, as I have maintained the spelling conventions used in Algeria. This generally implies following Frenchnot Englishphonetics in rendering words, names, and places and prioritizing popular usage over linguistic precision. You will read inchallah instead of inshaAllah, medersa instead of madrasa, moudjahidine instead of mujahideen, and you will wonder what has changed since that book on Egypt you read last summer. And thus you will get your own first taste of Algeriaa land that many expect to be just like its neighbors, but which instead surprises and confounds.

Prologue

Cut off the snakes tail, not itshead.

We will persist until the subjugationends.

The banner spanned the road several meters above my head, its message in blocky Arabic letters accompanied by a menacing cartoon cobra.

It was one of many such signs printed, stenciled, or handwritten in the last few days and strung from the balconies overlooking Rue Didouche Mourad, the main artery that wends its way downhill to the heart of Algerias capital, Algiers.

You fools betrayed and sold out thenation.

We, the poor, are reclaiming and buying back the nation at anycost.

When the government pushes the people toward ruin by every means, disobedience from every individual is not a right, but a nationalduty.

Our message is clear: We want freedom for thepeople.

The signs fluttered from the ornate colonial-era faades flanking the road, where a river of protesters flowed steadily toward downtown.

Amid this current, I tagged after a few friends while also taking time to simply absorb the ambiance. The day was overcast, cool but already humid, foretelling the long summer to come. All around, men and women carried colorful homemade placards asserting their independence, denouncing senior officials, or demanding a new constitution.

The Algerian flag, with its red star and crescent straddling fields of emerald green and white, was everywhere. Some draped the emblem over their shoulders like capes, others waved it through the air in time to a distant drumbeat. As they walked, the protesters shouted a mix of the latest anti-government slogans (Yetnahaw gaa, or Get them all out) and favorite soccer chants (One, two, three, viva lAlgrie).

Toddlers perched on parents shoulders, waving flags, while teens snapped selfies or browsed the patriotic swag at makeshift sidewalk stands. Residents perched on the railings above, watching the crowd stream past, while further overhead helicopters purred ominouslya rare sight before the protests began on February 22, 2019.

On that day, years of accumulated indignities and frustration had finally ignited, sparked by the news that Algerias president, ailing octogenarian Abdelaziz Bouteflika, would seek another term after twenty years in office.

In Africas largest country, the protests touched every city, small and large, from dusty towns in the deepest corners of the Sahara to the capital here on the shores of the Mediterranean. They swelled each Tuesday, when university students would skip class to demonstrate, and Friday, when Algerians of all stripes would occupy the streets.

On April 2, after six weeks of mounting protests, Bouteflika had announced his resignation. Algerians celebrated late into the night, then rushed to consult their constitution, which in such cases prescribed an interim leader.

Behind the scenes, however, lurked Algerias powerful army. After the presidents resignation, the generals let it be known that they would get around to installing that interim president soon. But meanwhile, they were prioritizing some housekeeping; within days, they fired the head of Algerias formidable intelligence services and folded the body under the militarys authority.

Judging from the crowd milling all around me, neither the presidents resignation nor these back-room machinations had placated anyone. It was April 5, and Algerians were marching for the seventh consecutive Friday. Seemingly every segment of Algerian society was in the street. The crowd thrummed with an excited energy.

With police deployed in huge numbers, that energy was partly nervous; historically, the Algerian police arent known for restraint in moments of crisis. In general, however, the ambiance felt overwhelmingly positive, reflecting just how long everyone around me had been waiting for this moment of release: when the wall of fear would finally break and every Algerian could scream their frustrations in the street. The regime might silence any one of them, but it could never silence all of them.

However positive the atmosphere, I wasnt taking chances. I had donned my sturdiest jacket and pants and laced my boots up tight before walking the few miles from my apartment. (Authorities had shut public transport, hoping in vain to slow the crowds swell.) With protesters chanting Peaceful!Peaceful! and encouraging calm whenever tempers flared, violence seemed unlikely, yet nothing was certain. I had lived in Algiers for six years and knew its geography like the back of my hand, but I had never felt this crackle in the citys air. And one thing was certain: if the situation went south, the foreigner would be the last to see it coming.

To top off my outfit, I slung on a baseball hat and pulled the brim down, trying in vain to keep a low profile. Yet even in a city of four million, I couldnt hide. My blond hair, while not unheard of in Algeria, wasnt common. Whats more, as a familiar face on Algerian social media, I was a known quantity around town. Algiers is nothing if not a small village, and before long I was spotted. So good to see you here, brother! my friend Samy shouted, elated to see a foreign face in the marchand all too glad to interpret my presence as an endorsement of the protests.