For my darling Flora and dear Jack May 2005. One in, one out

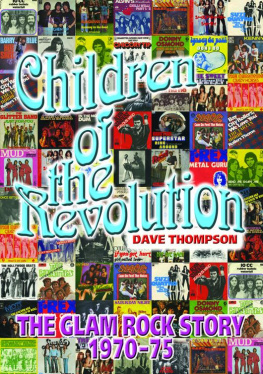

Copyright 2010 Omnibus Press

This edition 2010 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-237-7

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Visit Omnibus Press on the web: www.omnibuspress.com

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

Contents

Introduction

No Ulterior Motives?

Novelty 1 the quality of being new and intriguing. something new and strange. a small, cheap and usually kitsch toy or souvenir. 14c: from French novelt

Chambers 21st Century Dictionary

By nature, Sparks music isnt apt to appeal to much of a middle ground. Its childishness and its makers looks, looks, looks ensure its hold on the young, and its wry wit and perverto tinge should continue to captivate fringe types of all ages.

Richard Cromelin, Phonograph Record, 1975

The people who have the most trouble dealing with what weve been doing are the ones who analyse so much, the older rock fans. They tend to outguess our motives, and there are no ulterior motives.

Russell Mael, 1983.

Well, screw the past.

Ron Mael 2006

O ver its 40 year history, the flagship UK BBC TV music programme Top Of The Pops had its fair share of moments, when viewers experienced some sort of defining event. These usually coincided with a degree of early maturity and rebellion on the part of the observer. In some, this may have occurred in their early teens, some younger, watching pop as the twisted cartoon it often resembles.

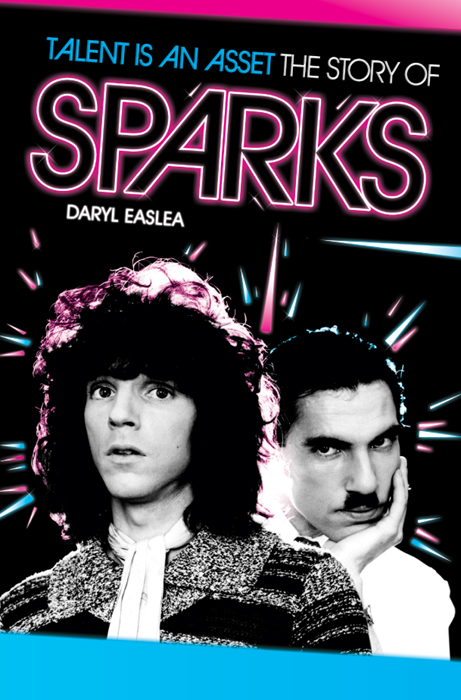

While David Bowie hugging Mick Ronson during Starman in 1972, or Johnny Rotten singing Pretty Vacant in 1977 are often cited, this author had his moment when, on May 9, 1974, five quirky individuals seemed to leap through the screen singing This Town Aint Big Enough For Both Of Us.

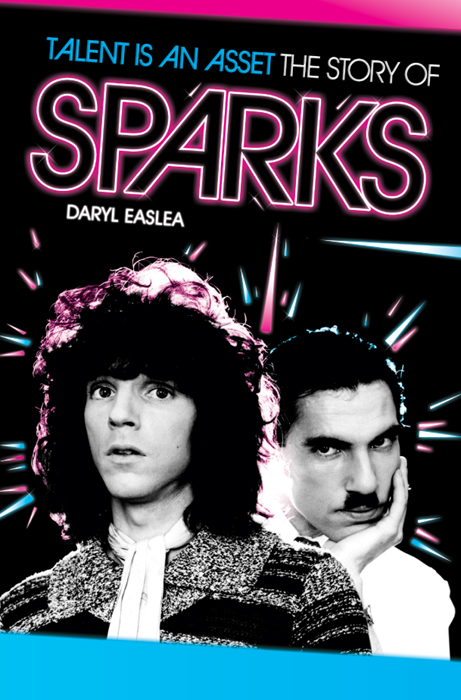

On an edition of the show that also featured in the studio easy listening crooner Vince Hill, soft toys The Wombles and boogie labourers Status Quo, stock still in front of us was a man rolling his eyes, bolted to the ground, exaggeratedly hitting his electric keyboard. He had slicked-back hair and a moustache. To his side, there was another man who looked vaguely similar, with curly flowing hair and what looked like a short dress on. A kimono, perhaps. Behind them were a fairly standard team of players from the day with their wide lapels, centre partings and flares. But it wasnt about them; it was all about the two men out front.

They looked like before and after pictures of an American small-town accountant who could take it no longer and had dropped out. However it was the size of the keyboard players moustache that made it all the more noteworthy. Covering no more than an inch underneath his nose, this facial hair seemed exceptionally familiar to everyone who was watching. It had been seen somewhere before; some thought perhaps of Oliver Hardy or Charlie Chaplin, to whom it was intended as tribute. Some thought of Stephen Lewis, Inspector Blake from the recently finished yet still hugely popular ITV comedy series On The Buses. But most, if not all, people thought of one person only Adolf Hitler.

And in 1974, the impact of the Second World War still cast something of a long shadow over Britain. Although it had been over for nearly 30 years, watching this spectacle was a generation whose parents had either fought in or had been born during the war. To find Hitler playing the piano on one of the BBCs prominent programmes was enough to send some older viewers into apoplexy.

This Town Aint Big Enough For Both Of Us became the soundtrack to that early summer and beyond; trips to the funfair, to town, to the park, presenting a macabre netherworld that stood apart from a chart that was frankly full of enough weirdos already. But even among the four-eyed vaudeville of Elton John, the mirrored-topper of Noddy Holder, the sinister Bacofoil of Gary Glitter and the androgyny of David Bowie, it still seemed bizarre. Ron Mael the wearer of this moustache looked something like the public information films warning of things youngsters did not yet quite understand: about men offering sweets and taking you for a ride in their cars.

And the other one, Rons younger brother, Russell, looked beautiful. It was as if he slept in a vat of moisturiser and lived a life being permanently startled in soft focus. Although it seemed nothing could be taken at face value; there was something about the speed of his delivery combined with a mixture of anxiety and supreme confidence that added to an overall unease.

It was about the clothes and the colour and the time. The taste of the exotic controlled and presented and beamed into the UKs living rooms. That Sparks were at their zenith in a Britain recovering from three-day weeks and the unrelenting grimness and relative poverty of the mid-Seventies comes now as little surprise. Lives were enlivened and brightened by the peacock people who would appear in our homes once a week. Aspirational values, cheap tailoring and the bizarre mingled together.

The long backwash of the moon landing of 1969 and the space films that followed, combined with a full-scale embracing of retro with the popularity of movies such as American Graffiti and The Great Gatsby, produced a generation of men (and it was mainly men as performers) who dressed like the future yet sounded like the past. Sparks were faintly straight compared to some acts but they had a man who looked like Adolf Hitler playing the piano, they looked striking, unusual, frightening, and they had made an impression, having scored the biggest hit single of their career.

The more we learned about this group, the more we, if not liked them, were intrigued. Ron wrote the songs and Russell sang them; theyd been in a group called Sparks before, but not this one; the pair supposedly had all sorts of connections to the American aristocracy; the Kennedys were fans; the Rainiers let them use their holiday home in Monaco; they were indeed the children of Doris Day.

Many people had a similar moment: teenage fan John Taylor, who six years later would form his own group called Duran Duran, felt equally strongly: Remember Bedazzled with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore? Theyre on that Top Of The Pops-style programme and Moore as Stanley Moon comes out and says I love you, I love you, the crowd goes crazy and then Peter Cook as the devil comes out and goes I hate you, I hate you. Well, Sparks was like watching both characters at the same time. Russell is so seductive and upfront, while Ron is holding everything back. Its a very strong presentation.

Next page