Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

For Natalie and Miles,

the music that saved me

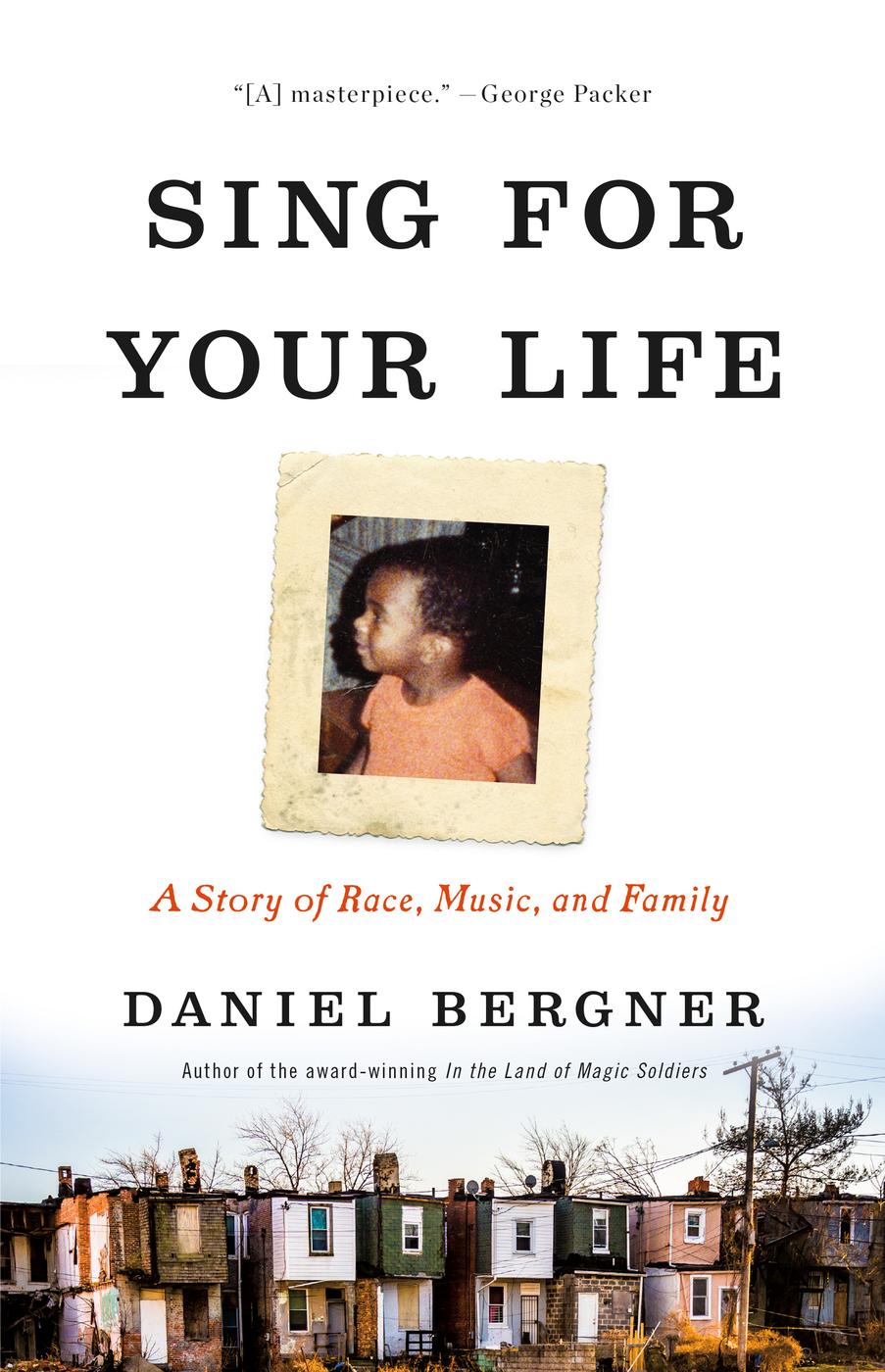

R YAN SPEEDO GREEN did not belong here. He didnt belong in the hotel room they had booked for him, where the headboard was high and plush and the light was faintly gold. There was more gold in the lobby, lots of it: the shimmering antique frame of the huge mirror beside the elevators; the austere silk curtains that rose three stories toward the vaulted ceiling; the velvet of the deeply curved couches; the abstract sculpture at the turn of the stairs.

Each time he left the lobby, passing under the hotels marquee and facing Lincoln Center, in the middle of New York City, he felt even less at home. He climbed the broad steps to the Lincoln Center plaza and was surrounded by towering white stone columns that made him think of ancient stadiumsOlympians competing for Zeuss pleasure and gladiators battling one another for survival. At the far side of the square stood the opera hall. This was the home of the Met, the greatest opera company in the country. The building looked as grand and remote as the White House.

As he started to traverse the plaza, the fountain ahead of him was almost inaudible. But as he neared the circular pool, the countless silvery plumes of shooting water created not a loud trickle or a concentrated splash: the heavy plumes produced a crescendo of sound that compounded the anxiety or thrill he felt on any given crossing of the square. It was a crossing he made repeatedly during those few daysin the early spring of 2011leading up to the semifinals of the contest.

Behind him, the clamor of the fountain hushed swiftly. In front of him were the giant poster stands, the posters announcing the seasons productions, lead singers photographed in dramatic shadow, and the opera housethe series of archways, the excess of glass, the vast murals with their airborne goddesses, their harp, cello, violins, horns. Beyond the windows hung an array of chandeliers with their pinpoints of pale gold light, and beyond the chandeliers was an aura of darker gold.

Backstage, awaiting his turn to sing, Ryan definitely did not belong, but there he was on the Sunday of the semis. This was the most revered competition in America for would-be opera stars. Twenty-two singers had made it this far after the district and regional rounds. Ryan was slotted eighteenth of the twenty-two for his minutes in front of the judges. He listened to the others; he couldnt escape their voices as he sat in the common area outside the dressing rooms, where their performances were piped in. But it wasnt only the voices themselves that confirmed how misplaced he was. It was the backgrounds of the other semifinalists. One had begun vocal training at seven, another at eight. His rivals brandished the invisible badges of having studied at the countrys most prestigious conservatories, at Curtis or the Academy of Vocal Arts or Juilliard. They not only belongedfor years they had been destined for this moment here at the Met.

Ryans home, in southeastern Virginia, was as much a shack as a house, with bullet holes above his mothers bedroom window. Before that, hed grown up in a trailer park; before that, in low-income housing. Along the way, he spent time locked up in Virginias institution of last resort for juveniles judged to be a threat to themselves or to everyone around them.

And Ryan was black. There was one other African American among the selected twenty-two, but shed had a much different upbringing. A part of hima driven, half-conscious partsang to make race disappear.

* * *

He was twenty-four years old. Waiting, he listened to Philippe, who had a low voice like his own, a bass-baritone, and the looks of a teen idol, with curly blond hair and fine expressive lips and a wisp of a nose. They had struck up an unlikely friendship during the past few days. Philippe was relentlessly confident. Walking through the corridors of the Met, he crooned out lines of SinatraFly me to the moon; let me play among the starsas if hed bypassed awe and deference and took for granted his place in this house. Never mind if famous singers and conductors heard him in the hallways.

With his turn several singers away, Ryan heard Philippe perform an aria by Wagner, probably the art forms most daunting composer. Philippe was one of the youngest contestants; they were all required to be between twenty and thirty. In the first round the previous fall, twelve hundred artists had sung in cities from Seattle to Philadelphia, Houston to Cincinnati to Boston. Ryans journey through the competition had started in Denver. He had a job, at seventeen hundred dollars per month, driving between Colorado towns with a small troupe and putting on drastically abridged operas in schools and community centers.

The contest had been inaugurated back in 1935, broadcast nationally by NBC radio and sponsored by the Sherwin-Williams paint company. The largest paint and varnish maker in the world takes pleasure in presenting the Metropolitan Opera Auditions of the Air! the nasally MC declared. Winners were guaranteed a Met contract. But gradually things had changed. The contest no longer had a corporate sponsor; it was no longer an advertising vehicle; it was funded by opera-loving benefactors. And it no longer gave out Met contracts. Even for the winnersand the judges usually named a few, depending on how they rated the talent when the final round was overa thriving career was far from certain. Yet there were winners from eras past who occupied operas pantheon, and some recent victors were ranked among the best opera singers in the world, and the Met made it known that the competition was a crucial way of finding promising artists to keep tabs on, so the prospect of being chosen seemed like the beginning of a fairy tale.

Philippes voice, full of gravity yet capable of elevating effortlessly, floated to a high plateau. He sounded, to Ryan, as though spirits had blessed him, lifted him.

Ryan heard Deanna, a soprano, carry out coloratura acrobatics. She did a tightrope walk with flourishes and flips, never so much as teetering. And Nicholas, a bass, offered the judges an entire lake of sound on his final note, a flawlessly smooth and seductive expanse.

By the time he was told to get to the edge of the stage, Ryan felt like he was evaporating. He stood six feet five and weighed over three hundred pounds. He wore size seventeen shoes. His biceps were about three times as big as an average mans. But he felt like his body was almost gone. It didnt help that to walk from the dressing area to the wings meant pushing through doors striped yellow and marked Do Not Enter. It didnt help that he had to pass through a long desolate space of rough wood and raw metal, the opposite of everything on the Mets public side. Multiple stories of backstage apparatus and nothingness loomed crushingly above him. With a couple of other singers, he waited in a tight, scarcely lit spot between a stage monitors booth and a set of immensely tall black curtains, three or four strides from the exposed part of the stage.