ALSO BY MATT BAI

The Argument: Billionaires, Bloggers, and the Battle to Remake Democratic Politics

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2014 by Matt Bai

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bai, Matt.

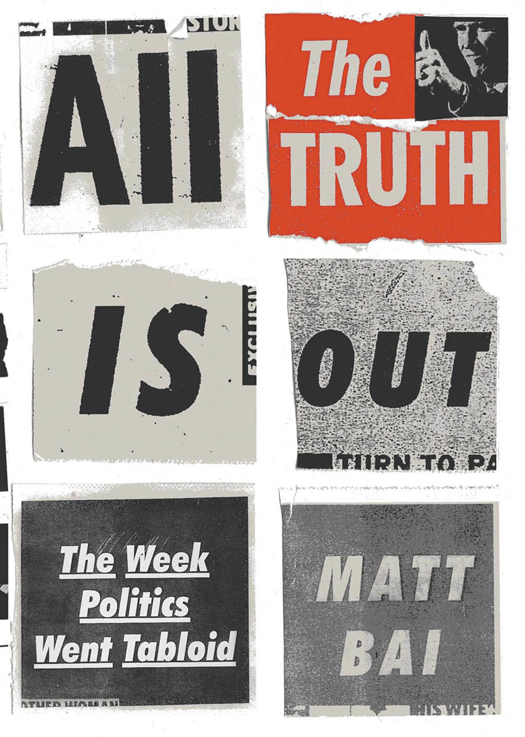

All the truth is out : the week politics went tabloid / Matt Bai.First edition. pages cm

A Borzoi bookTitle page verso.

ISBN 978-0-307-27338-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-385-35312-0 (eBook)

1. Hart, Gary, 1936Public opinion. 2. ScandalsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 3. Presidential candidatesPress coverageUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. Press and politicsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. Mass mediaPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 6. Tabloid newspapersUnited StatesHistory20th century. 7. CharacterPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 8. Public opinionUnited StatesHistory20th century. 9. LegislatorsUnited StatesBiography. 10. United States. Congress. SenateBiography. I. Title.

E840.8.H285B35 2014

328.73092dc23

2014001033

Jacket photograph: Associated Press

Jacket design by Peter Mendelsund

v3.1_r2

For Ellen

Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

CONTENTS

PREFACE

WHAT IT TOOK

ONE OF THE FIRST PEOPLE I CALLED after I decided to write this book in 2009 was Richard Ben Cramer. This was not a call I made lightly. I had, by this time, been writing about politics for The New York Times Magazine for the better part of a decade, so I was not exactly a journalistic unknown. But Richard was in a different category altogether. He was one of the greatest nonfiction writers of this or any age, and his seminal, 1,047-page chronicle of the 1988 presidential campaignWhat It Takes: The Way to the White Housewas arguably the greatest and most ambitious work of political journalism in American history.

We had talked by phone in the past, and I had written about him once, but never before had I sought his counsel. I feared finding out that one of my literary heroes was just another dismissive egoistthe business is full of themwho didnt have time to dole out advice.

About thirty seconds into the conversation, Richard invited me to lunch at the old farmhouse he shared with his girlfriend (and later wife), Joan, on Marylands idyllic Eastern Shore. Anytime I liked, he said, just pick a day, he wasnt doing much other than writing. The grace of that invitation wouldnt have surprised anyone who knew him.

The next week, I drove the ninety minutes down to Chestertown, where Richard treated me to a cheeseburger as we talked about the craft of journalism and the book I intended to write. I had come to believe that there was something misunderstood and significant in the story of Gary Hart, whose spectacular collapse Richard had followed in What It Takes. I thought the forces that led to Harts undoing were more complicated and more consequential, looking back now, than anybody had really appreciated at the time. I had in mind a book not simply about a single, captivating episode in American politics, but also about the cultural transformation it portended.

I confessed that I had begun to doubt myself, however. Almost invariably, when I mentioned this idea to colleagues and friends in Washington, they reacted as if I might be teasing themas if I had just said I was going to write my next book about bird migration or the Treaty of Westphalia. How could a discarded and discredited figure like Gary Hart possibly matter in the age of Obama? What did any of that have to do with the health care debate or the upcoming midterm elections? Maybe I should listen to the skeptics, I said to Richard. It seemed to me that there was a fine line between being visionary and being obstinate (Hart, more than anyone I could think of, illustrated this point), and most of us ended up on the wrong side of it most of the time.

Richard took all of this in, occasionally stroking his wispy beard or fiddling with his John Lennonlike glasses. And then he seemed to be in the grasp of a revelation, and he leaned back for a long moment and assessed me.

You dont want my advice! Richard said at last. You want my permission!

It was true. I did want his permissionnot to drill more deeply into the rich seam he had first mined back in 1987, but rather to defy the conventions of my peers.

Richard told me to honor my instincts, that the last people on earth who could discern the deeper currents of our politics were the people who covered and practiced it on a daily basis, obsessing over every poll and campaign filing. (Richard answered email only sporadically, and he probably never read a tweet in his life.) He reminded me that most of the nations journalism establishment had dismissed What It Takes, at the time it was published, as overwritten and impossibly long, and the book had all but disappeared for many years before a new generation discovered it. Why in the world, Richard asked me, would I listen to those people?

You didnt write a memorable book, he said, by giving people the story they were clamoring to read. You had to tell them the story they needed to hear.

What It Takes is an astounding worka contemporaneous biography of six different candidates, all portrayed from deep within their own psyches. Over the years, I have probably talked with a few dozen people who were subjects or sources in Richards book, and not one has ever complained of a single inaccuracy. The question you hear most often, when the subject of the book comes up, is how Richard did it. How did he get so many politicians and so many of their aides to open up the way they did? How did he come to find himself in their rooms, and in their cars, and frequently even on their couches for the night?

To know Richard was to know part of the answer, at least. His mind was open, his curiosity genuine and boundless. I have known celebrated reporters who give entire seminars on the art of eliciting candor from their subjectshow to put someone at ease, how to structure the questions, where to put the digital recorder. Richard trafficked in none of this witchery. His only trick was his sincerity, a yearning to understand the vantage point of whomever he was talking to. He listened, which is the most underrated skill in journalism, and probably in life.

But had Richard come along ten or even five years after he did, its doubtful that all the sincerity in the world could have yielded a book like What It Takes. Although this wasnt clear at the time, Richard undertook his lifes defining project at precisely the moment when the rules of politics and political journalism were about to change; his book was, in a sense, a bridge between the last moment, when generations of politicians had trusted most journalists and had aspired to be understood, and the next, when they would retreat behind iron walls of bland rhetoric, heavily guarded by cynical consultants.