F OR sharing their memories of Saul Bellow with me and giving me generous permission to draw on them in this book, I would like to thank Max Apple, Adam Bellow, Daniel Bellow, Alexandra Ionescu Tulcea Bellow, Jonathan Brent, Stanley Crouch, Maggie Staats Simmons, Joan Ullman, and Leon Wieseltier. I also want to thank my hosts at the University of Chicagos Committee on Social Thought in May 2015, when I presented a talk drawn from this book: Rosanna Warren, Robert Pippin, Nathan Tarcov, and David Wellbery. Their comments have improved the book substantially. The special collections division of the Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago kindly assisted me during my consultation of the Saul Bellow, Isaac Rosenfeld, and Tarcov family collections.

My editor, Matt Weiland, and his assistant, Sam MacLaughlin, at Norton have been a tremendous help with the writing of this book; I am grateful for their hard work and their insight. Thanks go as well to Laura Goldin and Remy Cawley at Norton, to David LaRocca for help with the notes, and to Trent Duffy for copyediting. My agent, Chris Calhoun, deserves special thanks for his belief in this project.

In this book I have relied extensively on four essential earlier volumes: James Atlass Bellow, Benjamin Taylors Saul Bellow: Letters and his edition of Bellows essays, There Is Simply Too Much to Think About, and Zachary Leaders To Fame and Fortune: The Life of Saul Bellow, 19151964. Ben Taylor and Zach Leader have shared their knowledge of Saul Bellow with me both informally and at a panel held at Columbia University in the fall of 2015; I wish to thank the organizer of that panel, Ross Posnock. My editors at Tablet magazine, David Samuels and Matthew Fishbane, and at the Nation, John Palatella, and at the Yale Review, J. D. McClatchy, gave me the chance to write about Bellow, for which I am also grateful. All three publications have given kind permission to reprint passages from these pieces in Bellows People.

The Houstoun Endowment at the University of Houston helped pay for permissions costs, as did the Deans Office of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences.

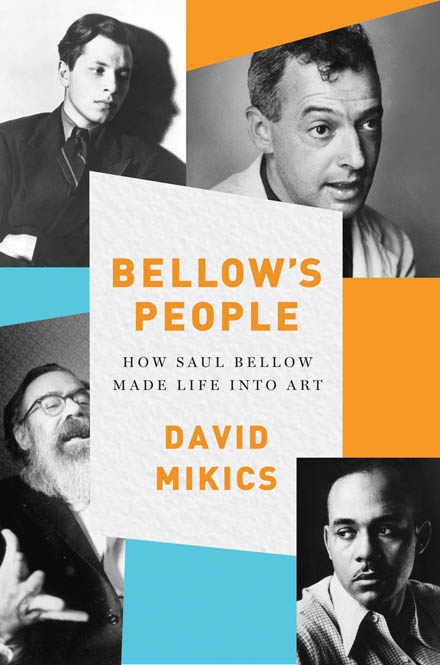

ALSO BY DAVID MIKICS

Slow Reading in a Hurried Age

The Annotated Emerson

Who Was Jacques Derrida? An Intellectual Biography

A New Handbook of Literary Terms

WITH STEPHEN BURT

The Art of the Sonnet

Copyright 2016 by David Mikics

Portions of Bellows People have appeared, in different form, in The

Yale Review (Spring 2014), The Nation (September 10, 2015), and

Tablet Magazine (June 10, 2015).

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this

book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please

contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com

or 800-233-4830

Book design by Fearn Cutler de Vicq

Production manager: Julia Druskin

ISBN 978-0-393-24687-2

ISBN 978-0-393-24688-9 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Bellows People

How Saul Bellow Made Life into Art

DAVID MIKICS

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923

NEW YORK | LONDON

I N A PHOTO taken sometime in the late fifties, the sizing-up gaze from dark-pool eyes, the Buster Keatonlike, chiseled cheekbones (Bellow the schoolboy was nicknamed Buster), the knowing mouth with its gap tooth, the wide, ready lips. Happy strong and open, which makes us happy too, this face, but just maybe about to take some advantage. The face of someone who lives on talk, appetite, settling accounts, and writing, writing himself and writing other people.

HE WAS GOING to take on more than the rest of us were, Alfred Kazin wrote about the young Saul Bellow, newly arrived in 1940s New York. He was waryeager, sardonic, and wary. Bellow, Kazin noted, was then not yet a novelist, much less a great one, but he had a pressing sense of his own coming destiny, like an old Jew who feels himself closer to God than anybody else.

A hundred years after he was born, Bellow may seem to us a figure from the past, a vigorous old uncle in danger of being forgotten by readers. But we cannot let go of him, because he has lessons for us that we need to hear. Few novelists have ever given us such a wealth of high-wire verve, the excitement of funny, passionate, overwrought people seeking and squabbling and contending. Bellows sentences live on the page, even burst from it. Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not, Emerson wrote. Bellows lines are loaded, every one.

The first lesson Bellow teaches is attention to personality. Bellow is our novelist of personality in all its wrinkles, its glories and shortcomings. Only through personality, he tells us, can we know the world. Bellow writes people in a way thats rare among novelists. His universe is physical: people are their bodies and their faces, and their souls shine through their flesh. Take the actor Murphy Verviger in Humboldts Gift, rehearsing at a Broadway theater that looks like a gilded cake-platter with grimed frosting: Verviger, his face deeply grooved at the mouth, was big and muscular. He resembled a skiing instructor. Some concept of intense refinement was eating at him. His head was shaped like a busby, a high solid arrogant rock covered with thick moss. Or Humboldt himself in his desperate last days: He wore a large gray suit in which he was floundering. His face was dead gray, East River gray. His head looked as if the gypsy moth had gotten into it and tented in his hair. Every Bellow fan has a mental list of such gloriously precise human pictures. In each one, Bellow shows how the psyche is right there in the flesh, ready to be seen. In Bellows descriptions, as James Wood comments, every detail is essential. He rivals even Dickens in his power to locate us through observation, to explain how appearances tell who we are.

Readers who love Bellows books are sometimes a little embarrassed, as if Bellow caters to an indulgence, a mere taste for excitable people and hyped-up talk. Bellow fans fear they might be out for gossip rather than some more respectable nourishment. But there is no reason for embarrassment. In Bellow personality is an exalted thing, and the novels have a mood of restless discovery. Every face, every line of dialogue, can be a revelation.

Personality is different from cultural identity, though cultural identity helps to form and shape personality. Nation, tribe, sex, all are part of us. These identities, as Bellow understands them, are the product of real, sometimes brutal historical experience rather than any deliberate choice. Sammler, in Mr. Sammlers Planet, never chose to be a Jew in Nazi-occupied Europe. Chicagos poor urban blacks, in The Deans December, didnt choose their particular misery either. When Sammler looks out on the sixties youth performing their hip ideal selvesguerrilla, long-haired cowboy, black pantherhe sees something that we twenty-first-century readers recognize. We can make ourselves interesting, we think, by putting on a style, a stance, an identity: we are what we wear, how we look, what we buy, what we tweet. Bellow is here to tell us that this is all an empty fantasy. Personality is marked in every face we meet, long before we begin our social role-playing.

Next page