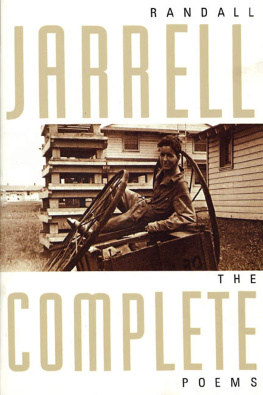

Randall Jarrell and His Age

Photo courtesy of the Randall Jarrell Collection, Special Collections Division of Jackson Library, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Randall Jarrell and His Age

Stephen Burt

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2002 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50095-1

My deepest thanks to Mary von Schrader Jarrell for permission to quote from previously unpublished writings by Randall Jarrell. My thanks as well to Farrar, Straus & Giroux and to Faber and Faber for permission to quote from The Complete Poems by Randall Jarrell and from Notebook by Robert Lowell.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burt, Stephen.

Randall Jarrell and his age / Stephen Burt.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0231125941 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Jarrell, Randall, 19141965. 2. United StatesIntellectual life20th century. 3. Poets, American20th centuryBibliography. 4. CriticsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

PS3519.A86 Z596 2002

811'.52dc21

2002071257

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

to Jessica Bennett

say: I am yours, Be mine!

CONTENTS

No large research projectcertainly none I could undertakecould bear fruit without the help and forbearance of many people; those thanked here are only some of them.

First of all I thank Mary Jarrell for the many kinds of help she has made available, in letters, in person and over the phone, and additionally through her published writings. Without her assistance this book could not exist. Having spent month after month in and around the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library, I owe much to it and to its staff, and especially to Stephen Crook. I am also indebted to the staff and resources of other manuscript collections: to the Library of Congress, to the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, to the Beinecke Library and the Yale Review manuscript files at Yale, to the Houghton Library at Harvard, and to Kate Donahue and the University of Minnesota.

Langdon Hammer advised the dissertation from which this book hatched and offered as much help as any student could wish. Jennifer Crewe, my editor at Columbia, provided important support and advice, as did Columbias two anonymous readers. My student Hannah Brooks-Motl proofread the whole work at a late stage, fixed glitches, and removed a truly startling number of semicolons. I am also grateful for comments, readings, advice, and assistance from Tim Alborn, Leslie Brisman, John Burt, David Bromwich, Suzanne Ferguson, Richard Flynn, Nick Halpern, John Hollander, James Longenbach, Jenn Lewin, Stuart McDougal, Thomas Otten, John Plotz, David Quint, Thomas Travisano, and especially Helen Vendler. The stubborn mistakes that remain are of course my own.

Parts of this book have appeared in journals and anthologies, sometimes in earlier versions. About half of appeared in PN Review. Manuscripts uncovered in the course of my work have appeared in the New York Review of Books, Thumbscrew, and the Yale Review. I am grateful to the relevant editors: Justin Quinn and David Wheatley; Suzanne Ferguson; Peter Forbes; J. D. McClatchy; Michael Schmidt; Robert Silvers; and Tim Kendall.

Without my parents, Jeffrey and Sandra Burt, none of this would be possible. Personal, and intellectual, help and happiness came from far too many people to list: some of the most important have been Jordan Ellenberg, Sara Marcus, Mike Scharf, and Monica Youn. Finally, this projectalong with everything else in my lifehas been improved beyond measure by Jessica Bennett, who sees how things are and knows how they ought to be; her understanding of art, proportion, and intimacy has, I hope, improved my own.

Randall Jarrell showed us how to read his contemporaries; we do not yet know how to read him. Often he seems to have understood the writers around him as posterity would: for some poets (such as Robert Lowell and Robert Frost) he helped to shape that posterity, while for others (such as Elizabeth Bishop) he prefigured it. Many readers know Jarrell as the author of several anthology poems (for example, The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner), a charming book or two for children, and a panoply of influential reviews. This book aims to illuminate a Jarrell more ambitious, more complex, and more important than that. He is ambitious partly because his writings refuse certain public ambitions. He is complex in part because his verse style tries so variously to use the artless simplicities of nonliterary speech. And he is important partly because he tells us to forget whether a book seems important, and to care instead for what strikes us as good.

The peers Jarrell admired mostBishop and Lowellnow belong to a so-called mainstream of American poetry, to which more radical or disjunctive writers are said to offer alternatives. Jarrell did not anticipate those developmentsif anything, they have made him harder to understand. To see how Jarrell wrote and how to read him is to see how he read his era, and how far his work stands from the course most American poets have followed since his death. It is also to see how Jarrells literary practice anticipated discoveries in Continental philosophy, in feminist psychology, even in political theory. And it is, finally, to see what he accomplished. To do so, we need to begin with ideas of the self.

Jarrell considered himself first and last a poet; his best-known prose concerns other poets poetry. Poetryor lyric poetry, or poetry since the Romantic erais frequently said to have as its province the inner life, or the psyche, or the self. That general vocation for poetry became Jarrells special project. His poems and prose describe the distances between the self and the world, the self and history, the self and the social givens within which it is asked to behave. They show how the self seeks fantasy, and how it turns to memory, as refuges from the demands the world makes on it, or from (worse yet) the worlds neglect. And they examine how the self seeks confirmation of its continuing existence, a confirmation it can finally have only through other people.

What does it mean to have a self to defend? Irving Howe writes that by asserting the presence of the self, I counterpose to all imposed definitions of place and function a persuasion that I harbor something else, utterly minea persuasion that I possess a center of individual consciousness that is active and, to some extent, coherent (24950). The philosopher Charles Taylor has shown how ideas of the self have evolved alongside certain notions of inwardness, which are peculiarly modern (498). The kinds of selves we find in modern literature, with their never fully revealed interior lives and their ties to autobiography (what Taylor would call expressive selves) have often been traced to early Romantic writers (Wordsworth, Goethe) or else to psychoanalysis. More than other American poets, Jarrell made sustained and self-conscious use of those sources.

According to Taylor, we have come to think that we have selves as we have heads. But the very idea that we have or are a self, that human agency is essentially defined as the self, is a linguistic reflection of our modern understanding (177). Taylor does not, however, wish to do away with the self: he does not think that we moderns should or can. Other thinkersespecially those indebted to Michel Foucaulthave liked to suggest that our notions of the self (or individuality, or interiority) are not only historically contingent but obsolescent, ethically suspect, and politically retrograde. Writing before poststructuralism exerted much influence on American letters, Jarrell took up other challenges to the self, challenges he saw throughout mid-century culturein supermarkets, in army barracks, in classrooms and lecture halls, on TV, and even within the family. Against all these he insisted that some sense of our presence in our own history, and of our inward difference from the rest of the world, remained prerequisite for our life with other people, for aesthetic experience, and even for ethical action.