HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

BOSTON NEW YORK 2011

Copyright 2011 by Eric Greitens

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Greitens, Eric, date.

The heart and the fist : the education of a humanitarian, the making of a

Navy SEAL / Eric Greitens.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-42485-9

1. Greitens, Eric, date. 2. United States. Navy. SEALsBiography. 3. United States.

NavyOfficersBiography. 4. United States. NavyOfficersTraining of. 5. Humanitarian

assistance, American. 6. United StatesArmed ForcesCivic action. I. Title.

V 63. G 74 A 3 2011

359.9'84dc22 [ B ] 2010026071

Book design by Robert Overholtzer, Boskydell Studio

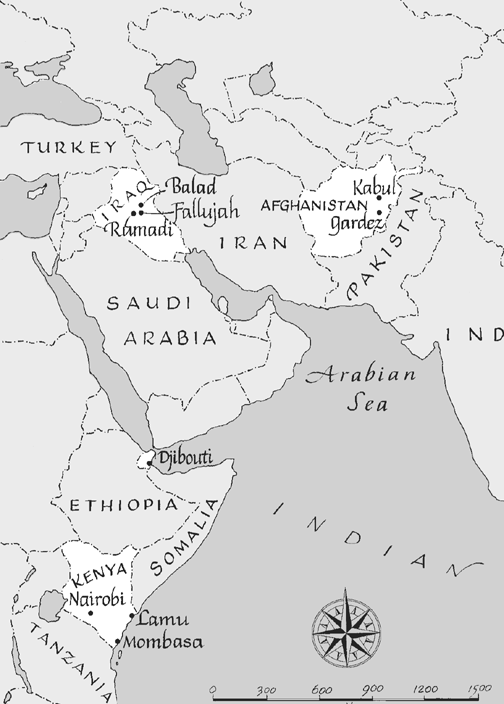

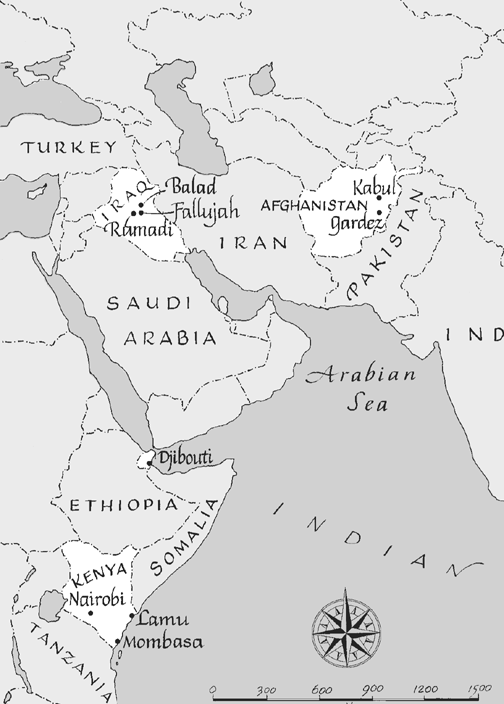

Maps by Jacques Chazaud

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO THE MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHERS

August Greitens, Chief Petty Officer, United States Navy

Harold Jacobs, Corporal, United States Army

Contents

Preface

I: MIND AND FIST

1. IRAQ

2. CHINA

3. BOXING

II: HEART AND MIND

4. BOSNIA

5. RWANDA

6. BOLIVIA

7. OXFORD

III: HEART AND FIST

8. OFFICER CANDIDATE SCHOOL

9. SEAL TRAINING

10. HELL WEEK

11. ADVANCED COMBAT TRAINING

12. AFGHANISTAN

13. SOUTHEAST ASIA

14. KENYA

15. IRAQ

EPILOGUE: THE MISSION CONTINUES

Author's Note and Acknowledgments

Notes

Preface

This is a book about service on the frontlines. I've been blessed to work with volunteers who taught art to street children in Bolivia and Marines who hunted al Qaeda terrorists in Iraq. I've learned from nuns who fed the destitute in Mother Teresa's homes for the dying in India, aid workers who healed orphaned children in Rwanda, and Navy SEALs who fought in Afghanistan. As warriors, as humanitarians, they've taught me that without courage, compassion falters, and that without compassion, courage has no direction. They've shown me that it is within our power, and that the world requires of usof every one of usthat we be both good and strong. I hope that the stories re-counted here will inspire you, as these people have inspired me. They have given me hope, and shown me the incredible possibilities that exist for each of us to live our one life well. For each of us, there is a place on the frontlines.

The Mission Continues A portion of the author's proceeds from the sale of this book will go toward supporting The Mission Continues. The Mission Continues empowers wounded veterans to serve again here at home and brings communities together to honor the fallen through service.

PART I: MIND AND FIST

1. Iraq

T HE FIRST MORTAR round landed as the sun was rising.

Joel and I both had bottom bunks along the western wall of the barracks. As we swung our feet onto the floor, Joel said, "They better know, they wake my ass up like this, it's gonna put me in a pretty uncharitable mood." Mortars were common, and one explosion in the morning amounted to little more than an unpleasant alarm.

As we began to tug on our boots, another round exploded outside, but the dull whomp of its impact meant that it had landed dozens of yards away. The insurgent mortars were usually wild, inaccurate, one-time shots. Then another round landedcloser. The final round shook the walls of the barracks and the sounds of gunfire began to rip.

I have no memory of when the suicide truck bomb detonated. Lights went out. Dust and smoke filled the air. I found myself lying belly down on the floor, legs crossed, hands over my ears with my mouth wide open. My SEAL instructors had taught me to take this position during incoming artillery fire. They learned it from men who passed down the knowledge from the Underwater Demolition Teams that had cleared the beaches at Normandy.

SEAL training... One sharp blast of the whistle and we'd drop to the mud with our hands over our ears, our feet crossed. Two whistles and we'd begin to crawl. Three whistles and we'd push to our feet and run. Whistle, drop, whistle, crawl, whistle, up and run; whistle, drop, whistle, crawl, whistle, up and run. By the end of training, the instructors were throwing smoke and flashbang grenades. Crawling through the mud, enveloped in an acrid hazered smoke, purple smoke, orange smokewe could just make out the boots and legs of the man in front of us, barbed wire inches above our heads...

In the barracks, I heard men coughing around me, the air thick with dust. Then the burning started. It felt as if someone had shoved an open-flame lighter inside my mouth, the flames scorching my throat, my lungs. My eyes burned and I squinted them shut, then fought to keep them open. The insurgents had packed chlorine into the truck bomb: a chemical attack. From a foot or two away I heard Staff Sergeant Big Sexy Francis, who often manned a .50-cal gun in our Humvees, yell, "You all right?"

Mike Marise answered him: "Yeah, I'm good!" Marise had been an F-18 fighter pilot in the Marine Corps who walked away from a comfortable cockpit to pick up a rifle and fight on the ground in Fallujah.

"Joel, you there?" I shouted. My throat was on fire, and though I knew that Joel was only two feet away, my burning eyes and blurred vision made it impossible to see him in the dust-filled room.

He coughed. "Yeah, I'm fine," he said.

Then I heard Lieutenant Colonel Fisher shouting from the hallway. "You can make it out this way! Out this way!"

I grabbed Francis's arm and pulled him to standing. We stumbled over gear and debris as shots were fired. My body low, my eyes burning, I felt my way over a fallen locker as we all tried to step toward safety. I later learned that Mike Marise had initially turned the wrong way and gone through one of the holes in the wall created by the bomb. He then stumbled into daylight and could have easily been shot. I stepped out of the east side of the building as gunfire ripped through the air and fell behind an earthen barrier, Lieutenant Colonel Fisher beside me.

On my hands and knees, I began hacking up chlorine gas and spraying spittle. My stomach spasmed in an effort to vomit, but nothing came. Fisher later said he saw puffs of smoke coming from my mouth and nostrils. A thin Iraqi in tan pants and a black shirt, his eyes blood red, was bent over in front of me, throwing up. Cords of yellow vomit dangled from his mouth.

I looked down and saw a dark red stain on my shirt and more blood on my pants. I shoved my right hand down my shirt and pressed at my chest, my stomach. I felt no pain, but I had been trained to know that a surge of adrenaline can sometimes mask the pain of an injury.

I patted myself again. Chest, armpits, crotch, thighs. No injuries. I put my fingers to the back of my neck, felt the back of my head, and then pulled my fingers away. They were sticky with sweat and blood, but I couldn't find an injury.

It's not my blood.

Next page