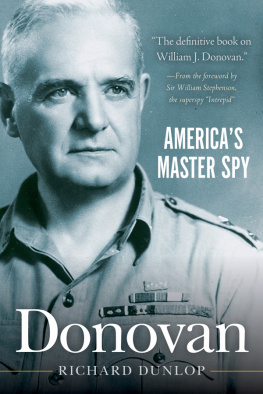

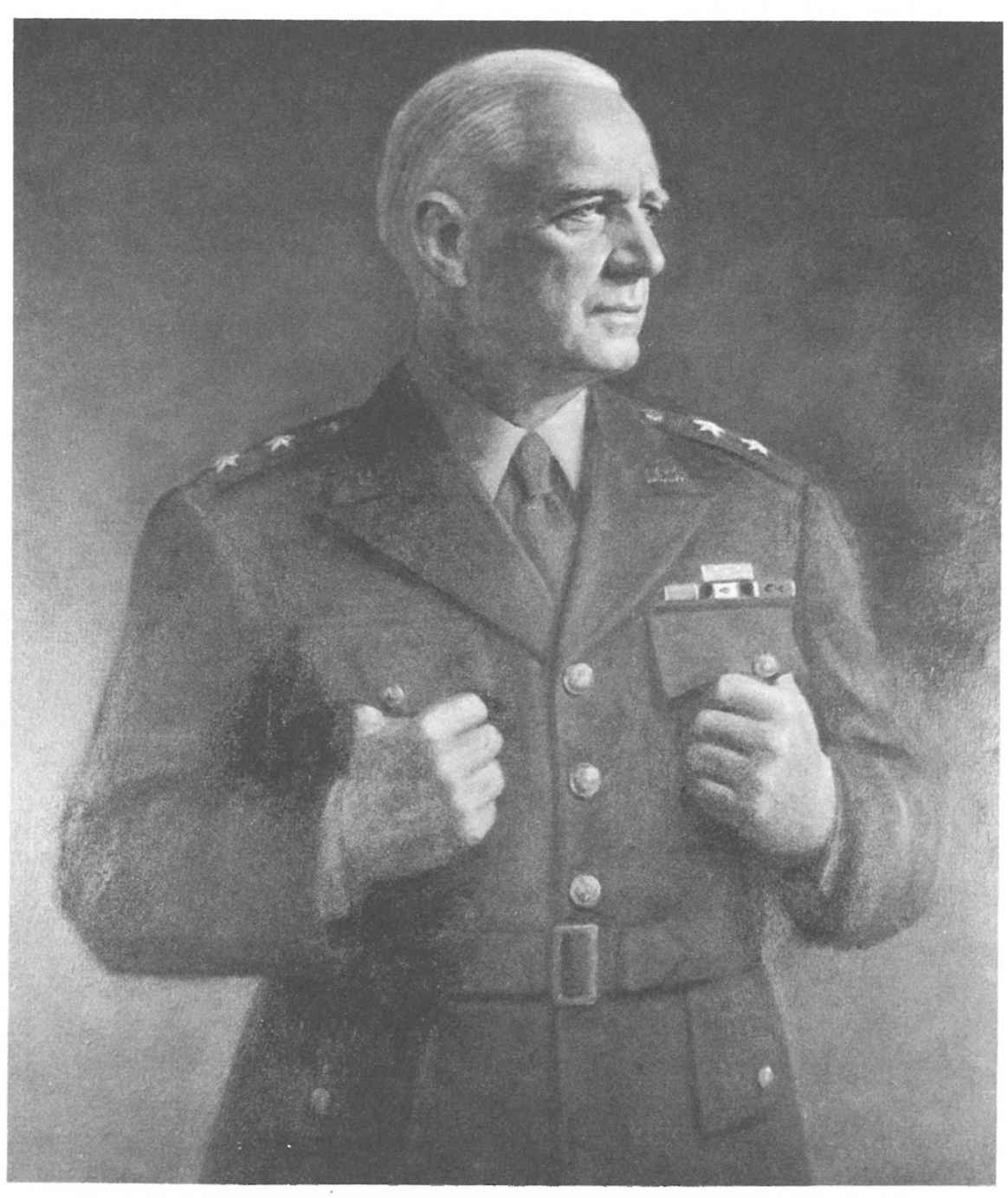

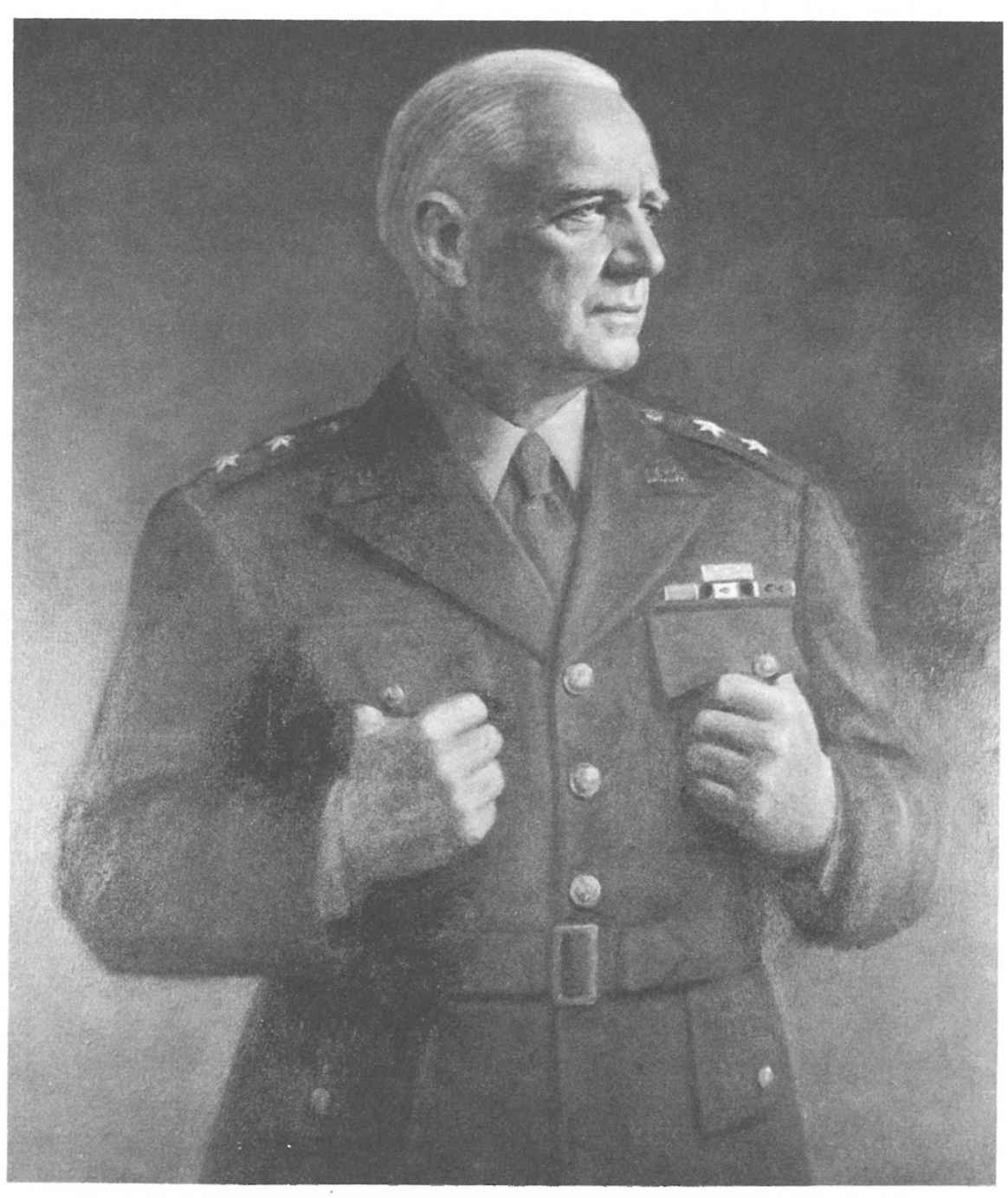

This painting of Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan greets the visitor to CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. Donovan is considered the father of American centralized intelligence.

Copyright 2014 by Richard Dunlop

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eISBN: 978-1-62873-898-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-539-1

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Foreword

On the day in May 1940 that Winston Churchill became prime minister, he telephoned me at my London home to say that he was dining with Max Beaverbrook and suggested that I join them. The dinner party was a serious affair. Other guests included Boom Trenchard of RAF and Scotland Yard fame, General Weygand of France, and Bill Hughes, prime minister of Australia. With the port and cigars Winston rose from his seat and beckoned to me. We walked over to the dining room window, heavily draped because of the blackout. Winston said quietly to me, Bill, you know what you must do at once. We have discussed it most fully, and there is a complete fusion of minds. So off you go. You will have the full support of every resource at my command, and God will guide your efforts as He will ours. This may be our last farewell, so au revoir and good luck.

It may be that at this late date I am thought of mainly as having been a regional representative of British Intelligence in the United States. My original charter went beyond that and indeed, under the master code name of Intrepid, was soon expanded to include representation in America of all the British secret and covert organizations, nine of them, and also security and communications. In fact, the communications division of my organization was by far the largest of its type in operation, handling more than a million message groups a day. In addition, there was the responsibility of acting as a go-between for Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt. My work as British Security Coordinator became an all-encompassing secret service.

I must enlarge a bit upon what were my principal concerns when I arrived in New York in late May 1940. Obviously, the establishment of a secret organization to investigate enemy activities and to institute adequate wartime security measures in the Western Hemisphere in relation to British interests in a neutral territory were of importance, and American assistance in achieving this goal was essential. The procurement of certain supplies for Britain was high on my priority list, and it was the burning urgency of this requirement that made me instinctively concentrate on the single individual who could help me. I turned to Bill Donovan.

By virtue of his independence of thought and action, Donovan inevitably had his critics. But there were few among them who would deny that he reached a correct appraisal of the international situation in the summer of 1940. At that time the United States government was debating two alternative courses of action. One was to endeavor to keep Britain in the war by supplying her with material assistance of which she was desperately in need. The other was to give Britain up for lost and to concentrate exclusively on American rearmament to offset the German threat. That the former course was eventually pursued was due in large measure to Donovans tireless advocacy of it.

Immediately after the fall of France, not even President Roosevelt himself could feel assured that aid to Britain would not be wasted in the circumstances. I need only remind todays readers that dispatches from the U.S. ambassadors in London and Paris were stressing that Britains cause was hopeless. The majority of the Presidents cabinet was of the same opinion. American isolationism was given vigorous expression by such men as Charles Lindbergh and Sen. Burton K. Wheeler. Donovan on the other hand was convinced that, granted sufficient aid from the United States, Britain could and would survive. It was my task first to inform Donovan of Britains most urgent requirements so that he could make them known in appropriate quarters, and second to furnish him with concrete evidence in support of his contention that American material assistance would not be improvident charity but a sound investment.

Very shortly after I arrived in the United States, Donovan arranged for me to attend a meeting with Secretary of the Navy Knox, Secretary of War Stimson, and Secretary of State Hull, where the main subject of discussion was Britains lack of destroyers. The way was explored for finding a formula for the transfer of 50 overage American destroyers to the Royal Navy without a legal breach of U.S. neutrality and without affront to American public opinion. It was then that I suggested that Donovan pay a visit to Britain with the object of investigating conditions at first hand and assessing for himself the British war effort. Donovan conferred with Knox, and they jointly conferred with the President. Donovan left by Clipper July 14, on one of the most momentous missions ever undertaken by any agent in the history of western civilization.

I arranged that he should be afforded every opportunity to conduct his inquiries. I endeavored to marshal my friends in high places to bare their breasts. He was received in audience by the king. He had ample time with Churchill and members of his cabinet. He spoke with industrial leaders and with representatives of all classes in Britain. He learned what was truethat Churchill, defying the Nazis, was no mere bold facade but the very heart of Britain, which was still beating strongly.

Donovan flew back to America in early August, and shortly after his arrival I was able to inform London that his visit had been everything I had hoped for. Donovan and Knox pressed the destroyers-for-bases case with the President despite strong opposition from below and procrastination from above. At midnight of August 22, 1940, I was able to report to London that the destroyer deal was agreed upon, and that 44 of the 50 ships were already commissioned. It is certain that the destroyers-for-bases deal would not have eventuated when it did without Donovans intercession, and I was instructed to convey to him the warmest thanks of His Majestys Government.

My work with Donovan could be described as covert diplomacy. There were other supplies that he was largely instrumental in obtaining for Britain during the same period. Among them were 100 Flying Fortresses for RAF Coastal Command and a million American rifles and 30 million rounds of ammunition for the British Home Guard, who were then mock training with broomsticks. During the early winter of 1940 His Majestys Government was especially concerned to secure the assistance of the U.S. Navy in convoying British merchant shipping across the Atlantic. This was a measure of intervention that the U.S. government was understandably reluctant to take. Donovan pleaded the case for us at a meeting with Knox, Stimson, and Hull in December 1940. This conference led to Donovans second trip. There was more to it than that, since Churchill wanted an influential American to apply some subtle delaying tactics in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, which might affect the timetable of Hitlers expected attack on Russia.

Next page