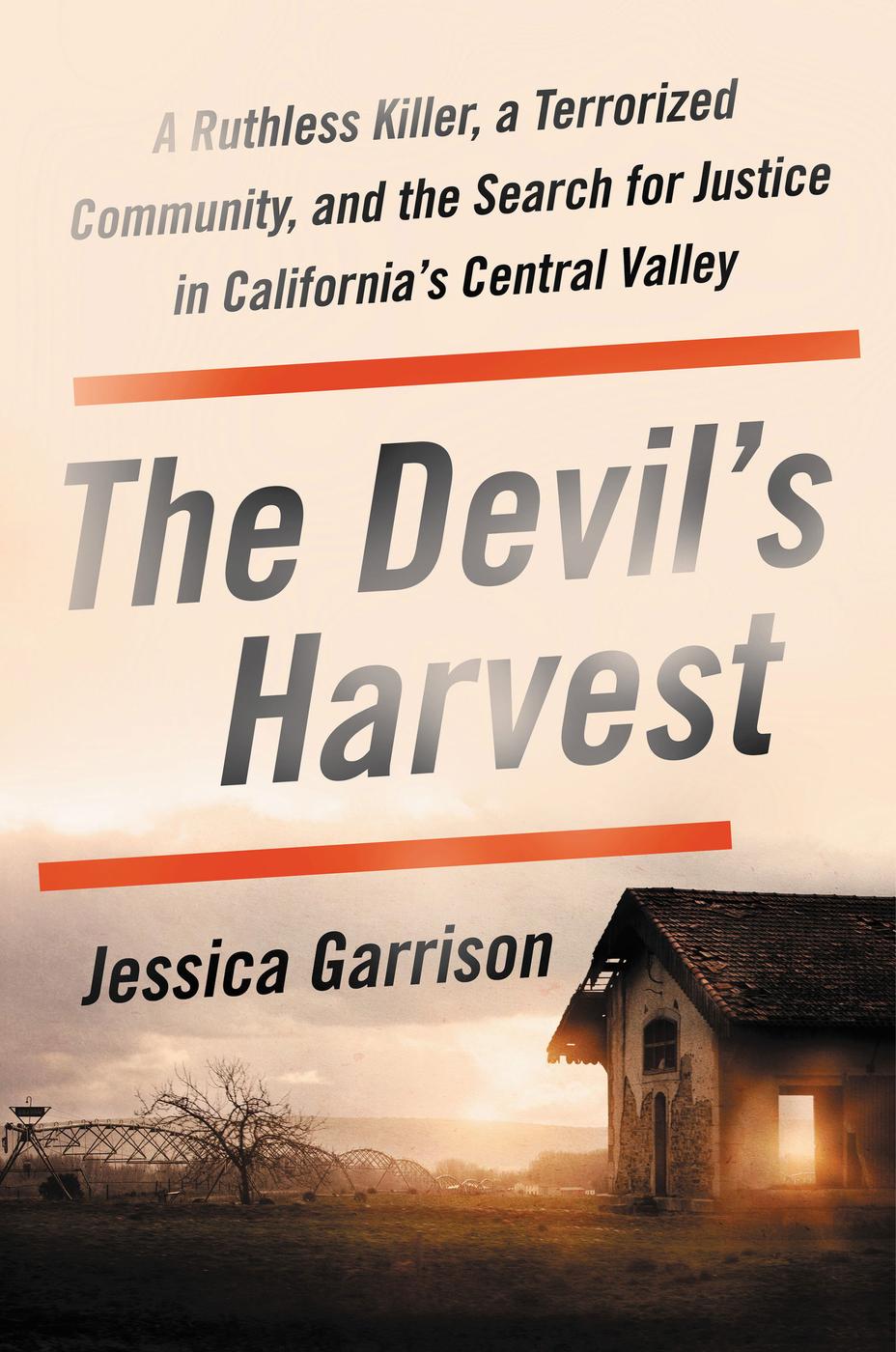

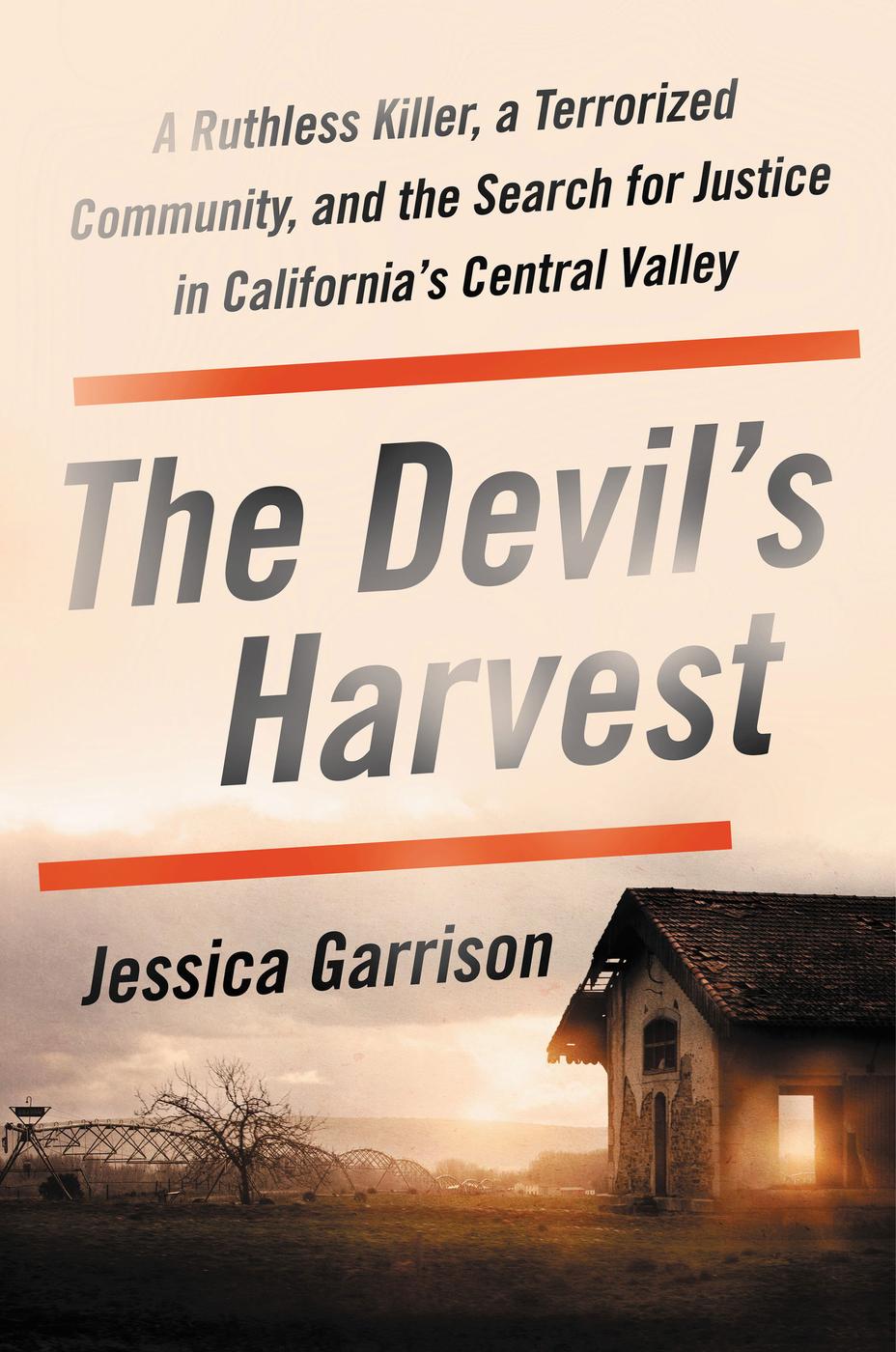

Copyright 2020 by Jessica Garrison

Cover design by Robin Bilardello

Cover photograph Estersinhache fotografa / Getty Images

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

First Edition: August 2020

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Print book interior design by Marie Mundaca.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garrison, Jessica, author.

Title: The devils harvest : a ruthless killer, a terrorized community, and

the search for justice in Californias Central Valley / Jessica Garrison.

Description: First edition. | New York : Hachette Books, [2020] | Includes

bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019055804 | ISBN 9780316455688 (hardback) | ISBN 9780316455732 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Martinez, Jose Manuel, 1962 |

MurderersCaliforniaCentral ValleyCase studies. | Serial

murdersCaliforniaCentral ValleyCase studies. | Latin

AmericansCrimes againstCaliforniaCentral ValleyCase studies.

Classification: LCC HV6248.M4325 G37 2020 | DDC 364.152/32092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019055804

ISBNs: 978-0-316-45568-8 (hardcover), 978-0-316-45573-2 (ebook)

D3-20200625-DA-NF-ORI

For Michael

And in loving memory of

Courtney Everts Mykytyn

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

I first heard of Jose Manuel Martinez in the spring of 2014. The Associated Press reported that a man accused of murdering nine men over a span of three decadesand suspected of killing many morewas being extradited from Alabama to California. Police believed they had caught a professional hit man.

At the time, I was an editor for the Los Angeles Times, and I dispatched the papers Fresno correspondent seventy miles south down Highway 99 to Tulare Countythe heart of Californias farm beltto see what she could learn. After the report ran, I found I could not stop thinking about his case.

How could someone get away with murder after murder for more than thirty years while living in a sleepy, close-knit farmworker town where everyone knew everyone else?

Eventually, Martinez himself would explain it to me. He was so damn good, hed say. He left little evidence and few witnesses.

This was true but far from the whole story. Martinez, I learned, had been born and raised in Californias vast Central Valley, which stretches about 450 miles down the interior of the state and is one of the richest farming regions in the world. He came from its stark and beautiful southern end, known as the San Joaquin Valley, where the peaks of the Sierra Nevada march upward toward their apex at Mount Whitney and where, down on the valley floor, any notion of California as a progressive, egalitarian land of opportunity disintegrates under the relentless, baking sun.

Nearly half the fruits and nuts that Americans eat are grown here, in lavishly irrigated fields that roll out like a green carpet across the once-arid land.

This is where John Steinbeck set his Depression-era classic The Grapes of Wrath and where, in the 1960s, Cesar Chavez launched his crusade to organize farmworkers, drawing the support of national politicians, activists, and celebrities. Yet even now, in the third decade of the twenty-first century, the Central Valley, particularly the San Joaquin Valley, remains a disturbing tableau of American inequality.

Growing up here to witness routine exploitation, shocking violence, and seemingly capricious police officers, Martinez assessed the circumstances and decided murder for hire was a reasonable way to make a living. And his greatest asset as a killer, it became clear to me, was that he had grasped a dark truth about the American justice system: if you kill the right peoplepeople who are poor, who are not white, who may be presumed to be criminals themselves, and who dont have anyone to speak for themyou can get away with it. El Mano Negra, the Black Hand, as Martinez was known, had found an ideal place to ply his trade.

Cecilia Camacho, a relative of one of Martinezs victims, knew this truth as well as Martinez. There is no follow-through when the [victim] is from Mexico. We didnt have papers. We didnt have the means to speak up for ourselves.

It was a familiar refrain. As I dug into the case, I tracked down other family members of Martinezs victims, their anguish and loss not lessened over the years or decades since their loved ones were killed. But I was struck most by how they had carried their suffering without public protest. Many say they were silenced not so much by fear of El Mano Negra as by the conviction that no one in powernot the police brass or the elected officials or the mediareally cared what had happened to their fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons. Or to their communities.

Year after year, Martinez operated with impunity. In Tulare County, where he lived for decades, officials suspected him of murder after murder and yet never charged him. Next-door Kern County, where he also lived for a time and committed several murders, has one of the highest murder rates in California and one of the lowest murder-solve rates in the nation. Martinezs hometown of Earlimarta tightly woven community where people knew each others stories and watched out for each others childrenwas also so violent, some nicknamed it Murdermart. In other places, Martinez killed people in out-of-the-way areas and then vanished before anyone thought to look for him.

Eventually, after speaking with victims family members and the police officers who investigated those cases, I reached out to Martinez himself. I addressed a letter to him, care of the jail where he was awaiting trial. I have written many such letters to prisons in my years as a reporter, and I knew better than to expect a response. But a few weeks later, my phone rang.

How are you? Martinez asked me. I was flustered, then stunned, as so many police officers had been before me, by how personable this cold-blooded killer sounded. What do you want to know?

At that point, I knew only the broad outlines of Martinezs story. I knew he had killed many people in a place where justice had always been in short supply. I also knew from police that he was a devoted father and grandfather who lived to make the children in his family laugh.

I told Martinez I was interested in why he had murdered so many people and how he had gotten away with it. I told him that I was curious, too, about how he could kill without remorse, sometimes, it seemed, even with relish, and at the same time be so generous toward his family.