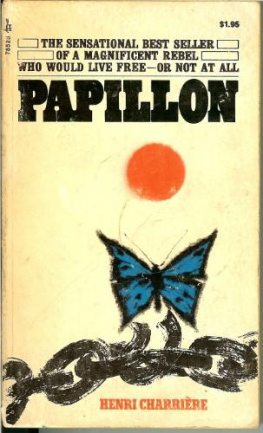

HENRI CHARRIRE

Papillon

Translated from the French by

PATRICK OBRIAN

To the people of Venezuela, to the humble fishermen of the Gulf of Paria, to all those, intellectuals, soldiers and others who gave me my chance to make a new life.

To Rita, my wife, my best friend.

Contents

All this last year France has been talking about Papillon, about the phnomne Papillon, which is not merely the selling of very large numbers of an unusually long book, but the discovery of a new world and the rediscovery of a kind of direct, intensely living narrative that has scarcely ever been seen since literature became self-conscious.

The new world in question is of course the underworld, seen from within and described with extraordinary natural talent by one who knows it through and through and who accepts its values, which include among others courage, loyalty and fortitude. But this is the real underworld, as different from the underworld of fiction as the act of love is different from adolescent imaginings, a world the French have scarcely seen except here and there in the works of Jean Genet and Albertine Sarrazin, or the English since Defoe; and its startling fierce uncompromising reality, savagely contemptuous of the Establishment, has shocked and distressed many a worthy bourgeois. Indeed, we have a ministers word for it (a minister, no less) that the present hopeless moral decline of France is due to the wearing of miniskirts and to the reading of Papillon.

Nevertheless all properly equipped young women are still wearing miniskirts, in spite of the cold, and even greater numbers of Frenchmen with properly equipped minds are still reading Papillon, in spite of the uncomfortable feelings it must arouse from time to time. And this is one of the most striking things about the phnomne Papillon: the book makes an immense appeal to the whole range of men of good will, from the Academie franaise to the cheerful young mason who is working on my house. The literary men are the most articulate in their praise, and I will quote from Franois Mauriac, the most literary and articulate of them all, for his praise sums up all the rest and expresses it better. This piece comes from his Bloc-notes in the Figaro littraire.

I had heard that it was a piece of oral literature, but I do not agree at all: no, even on the literary plane I think it an extraordinary talented book. I have believed that there is no great success, no overwhelming success, that is undeserved. It always has a deep underlying reasonI think that Papillons immense success is in exact proportion to the books worth and to what the author has lived through. But another man who had had the same life and had experienced the same adventures would have produced nothing from it at all. This is a literary prodigy. Merely having been a transported convict and having escaped does not mean a thing: you have to have talent to give this tale its ring of truth. It is utterly fascinating reading. This new colleague of ours is a master!

A thing that struck me very much in the book is that this man, sentenced for a killing that he did not committakes a very sanguine view of mankind. At the beginning of his first escape he was taken in and given shelter on a lepers island. The charity these most unfortunate, most forsaken of men showed to the convicts is truly wonderful. And it was the lepers who saw to it that they were saved. The same applies to the way they were welcomed in Trinidad and at Curaao, not as criminals but as men who deserved admiration for having made that voyage aboard a nutshell. There is this human warmth all round them, and all through the book we never forget it. How different from those bitter, angry, disgusted books Clines, for example.

Mans highest virtues are to be found in what is called the gutter, the underworld; and what gangsters do is sometimes the same as what heroes do. I have already confessed that when I am very low in my mind I read detective stories. In these books, where everything is made up, the human aspect of the characters, the humanity, is appalling. But in Papillons tale, which is true, we meet a humanity that we love in spite of its revolting side. This book is a good book, in the deep meaning of the word.

When one has read a little way into Papillon one soon comes to recognize the singular truthfulness of the writing, but at first some readers, particularly English readers, wonder whether such things can be; and so that no time, no pleasure, should be lost, a certain amount of authentication may be in place.

Henri Charrire was born in 1906, in the Ardche, a somewhat remote district in the south of France where his father was the master of a village school. After doing his military service in the navy, Charrire went to Paris, where, having acquired the nickname of Papillon, he soon carved himself out a respected place in the underworld: he had an intuitive perception of its laws and standards, and he respected them scrupulously. Papillon was not a killer at that time, but he fell foul of the police and when he was taken up on the charge of murdering a ponce he was convicted. The perjury of a witness for the prosecution, the thick stupidity of the jury, the utter inhumanity of the prosecuting counsel, and the total injustice of the sentence maddened him, for like many of his friends he had a far more acute sense of justice than is usual in the bourgeois world. What is more, the sentence was appallingly severe transportation to the penal settlements in French Guiana and imprisonment for life without a hope of remission: and all this at the age of twenty-five. He swore he would not serve it, and he did not serve it. This book is an account of his astonishing escapes from an organization that was nevertheless accustomed to holding on to thousands of very tough and determined men, and of the adventures that were the consequences of his escapes. But it is also a furious protest against a society that can use human beings so, that can reduce them to despair and that can for its own convenience shut them up in dim concrete cells with bars only at the top, there to live in total silence upon a starvation diet until they are tamed, driven mad or physically destroyed killed. The horrible, absolutely convincing account of his years in solitary confinement is very deeply moving indeed.

After years on the run, years of being taken and then escaping again even though he was on the very dangerous list, Papillon finally got away from Devils Island itself, riding over many miles of sea to the mainland on a couple of sacks filled with coconuts. He managed to reach Venezuela, and eventually the Venezuelans gave him his chance, allowing him to become a Venezuelan citizen and to settle down to live in Caracas as quietly as his fantastic vitality would allow.

It was here that he chanced upon Albertine Sarrazins wonderful lAstragale in a French bookshop. He read it. The red band round the cover said 123rd thousand, and Papillon said, Its pretty good: but if that chick, just going from hideout to hideout with that broken bone of hers, could sell 123,000 copies, why, with my thirty years of adventures, Ill sell three times as many. He bought two schoolboys exercise books with spiral bindings and in two days he filled them. He bought eleven more, and in a couple of months they too were full.