Victoria Lomasko

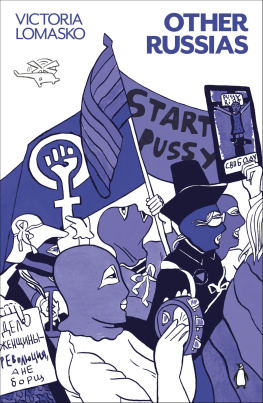

OTHER RUSSIAS

Translated from the Russian by Thomas Campbell

PENGUIN BOOKS

OTHER RUSSIAS

Victoria Lomasko was born in Serpukhov, Russia in 1978. She works as a graphic artist and has lectured and written widely on graphic reportage. The co-author of the book Forbidden Art, nominated for the Kandinsky Prize in 2010, she has also co-curated two major art exhibitions, The Feminist Pencil and Drawing the Court. Her work has been exhibited in numerous shows in Russia and abroad. She lives in Moscow.

This book is dedicated to Bela Shayevich and Thomas Campbell

INT RODUCTION

This book collects my graphic reportage from 2008 to 2016, years I spent traveling to Russian cities and villages to speak with people who live on the margins of Russian society. Based in drawings produced from life (rather than reproduced from photographs), this work addresses two broad subjects, and thus comprises two sections: Invisible and Angry.

Invisible contains stories about juvenile prison wards, teachers and pupils at rural schools, migrant workers, old people seeking refuge in Russian Orthodoxy, sex workers, and single women in the Russian hinterlands. As the majority of the Russian populace is invisible to itself and to the rest of the world, this section could be expanded indefinitely. What makes these subjects distinct, however, and distinctly invisible, is their social isolation: they have no way to move up in life, and no access to the public arena.

Angry, meanwhile, chronicles peoples attempts to come together and take back their voice and rights from the state. It includes reports of the large opposition rallies that took place in Moscow in 2012 and the subsequent trials of protesters; the LGBT communitys efforts to stay visible despite the governments adoption of homophobic laws; and protests by national and local grassroots pressure groups in 2015 and 2016.

Graphic reportage may strike Western readers as a strange or hybrid genre. While my stories may be read through the prism of European and American nonfiction or documentary comics, they were produced under different circumstances and with a different tradition in mind. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the official Union of Artists and its obligatory socialist realism were replaced by contemporary art institutions that championed, with equal fervor, socialist realisms supposed opposite: Western conceptualism and an unspoken taboo on realistic figurative art, especially life drawing. In 2007, the Russian art critic Ekaterina Degot wrote, If an artist wants to do something really scandalous today, something that will get them turned down for an exhibition, they should produce a realist oil painting. Or draw a human figure with pencil on paper.

At the fashionable art school I attended after earning a bachelors degree in art from a more conventional university, my first work of graphic reportage was rejected out of hand. I was told that no one drew from life in the 21st century. But I felt the need to complete my drawings on the spot, to serve as a conductor for the energy generated by events as they happened. I refused to make drawings from photos and videos.

The usual methods of Western documentary comics were not conducive to what I wanted to do, either, since their frame-by-frame layout felt at odds with the sense of immediacy that I was after. Finding no guides among my contemporaries, I turned to the practices of the 19th and 20th centuriesnamely to the albums produced by Russian soldiers, concentration camp inmates, and people who experienced the Nazi siege of Leningrad. In many cases, urgent work like this was the only kind of reporting that was done in these brutal conditonsthese albums were the sole acts of witness. In such circumstances, what kind of responsibility does an artist have? What I was trying to do, above all, was to break through to a more direct grasp and reflection of the reality around me.

Pursuing this kind of life drawing was also my way of protesting the insular Russian art scene, and the complete social alienation of artists from viewersand vice versa. The people from different social groups whose lives I reported on also had scant notion of how other social classes in their own country lived. To present a true picture of Russian society, I found I had to become an independent researcher, journalist, and activist. I made working at the crossroads of journalism and human rights activism my creative method.

The book shows how Russian society has been changed in recent years by pervasive censorship, the passage of new laws controlling virtually all aspects of life, and the utter fusion of the Russian Orthodox Church with the bureaucracy. (Just compare the outsiders in A Prayer Against the General Plan with the confident members of the grassroots Orthodox movement Multitude, who appear in the books final piece, Truckers, Torfyanka, and Dubki.) On the other hand, discontent and anger have long been growing, engulfing parts of society once indifferent to politics and loyal to the authorities.

Over the years, my approach has changed. In 2008, my only desire was to avoid getting stuck in the sterile white cube of the gallery and get over my fear of reaching out to ordinary people. At first, I returned to the practice of sketching in public places but added what my subjects were saying to the drawings. I eavesdropped and spied on them. Then I worked up the courage to engage them in conversation and ask questions. Later, I began to approach my subjects as a journalist would, traveling to various places to research topics that fascinated me.

I hope my graphic reportage from this eight-year period will give readers insights into Russian society and a sense of the changing social and political landscape. I think of what follows as a story of ordinary people, unfolding against the larger background of history.

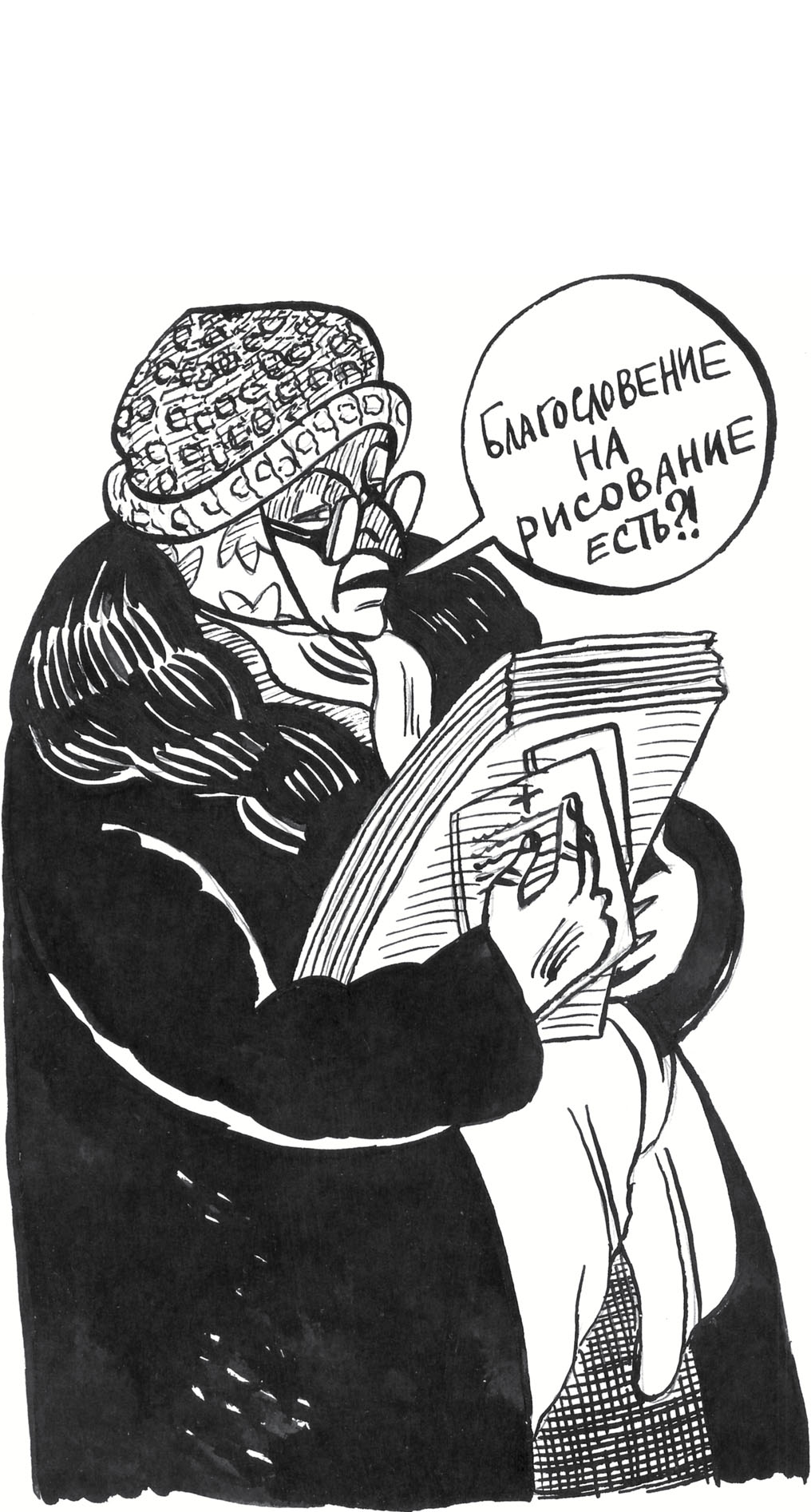

Do you have a priests blessing to draw us?

BLA CK PORTRAITS

I drew each of the following portraits after a chance meeting with a stranger who wanted to tell me about his or her life. Such situations cannot be forced, so this series of eight drawings took shape over three years. For example, the old retired teacher suddenly sat down next to me in a Moscow suburban train. The tattooed young man approached me in a hospital courtyard, while the stonemason, Sergei, came up to me at a protest rally by Russian Orthodox activists. (You will meet Sergei again in the next series, .) The circumstances in which these people found themselves were painful, so I decided to use a black background for the portraits.

The views and attitudes evinced by the sitters in Black Portraits are quite typical of our society. Especially telling is the diptych that emerged between the portraits of Sergei and Viktor, a lecturer in political science. It embodies the prevailing political moods in Russia: the poor and less educated social groups are opposed to the West, while the intelligentsia despises the common folk.

![Stephan Orth - Behind Putin's Curtain: Friendships and Misadventures Inside Russia [aka Couchsurfing in Russia]](/uploads/posts/book/860709/thumbs/stephan-orth-behind-putin-s-curtain-friendships.jpg)