For South Africa

I n the first instance I must thank my old friend James Lemoyne, who knows me so well he knew I had to write this book before I did. It was his idea that I should do it, and he was a source of constant encouragement and valuable insights as I set about the task.

My agent Anne Edelstein was even sharper on the draw than usual in getting this book out to the publishing world and also proved to be my trusty first line of editorial defense. Not for the first time, she has acted above and beyond the call of duty.

My editor at HarperCollins, David Hirshey, his assistant, Sydney Pierce, and other members of his team, not least Susan Amster, the eagle-eyed lawyer, performed skilled, Trojan labor on this manuscript, improving my words and honing my thoughts with rare persistence and rigor. It was an immense comfort and a pleasure to be in such good hands.

I should also note my debt to the various colleagues I worked alongside in the making of a number of film documentaries about Mandela, notably Cliff Bestall, Indra Delanerolle, and David Fanning. A fair chunk of the material in this book was gleaned during the work we did together.

Finally, a special thanks to my friend Michael Shipster, who really knows his stuff on Mandela and South Africa, and was kind enough to read the original manuscript and offer plenty of choice improvements on it. Thanks as well, and as ever, to Sue Edelstein and to my son James Nelson Carlin, who I hope will read this book one day (or else!) and learn the supreme value of kindness from his immortal namesake.

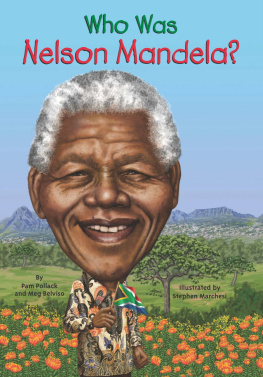

Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and

the Game That Made a Nation

JOHN CARLIN is an award-winning journalist who has reported for the worlds leading publications, including the New York Times , the Wall Street Journal , and TIME . His previous book, Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game That Made a Nation , is the basis for the Clint Eastwood film Invictus . John splits his time between London and Barcelona, and his chief delight in life is his thirteen-year-old son, James.

Visit www.AuthorTracker.com for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

http://www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W, 1A8, Canada

http://www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

10 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10022

http://www.harpercollins.com

THE PRESIDENT AND

THE JOURNALIST

C ondemned in 1964 to life in prison for taking up arms against the state, he was supposed to have died in a small cell on a small island. Yet here was Nelson Mandela, almost thirty years later, standing before me, no longer a prisoner of that state, but the head of it. Barely a month had passed since he had been elected president of South Africa when he welcomed me into his new office at the Union Buildings in Pretoria, wearing his large and familiar smile, enveloping my hand in his enormous one, leathery after years of forced labor. Ah, hello, John! he cried with what felt like genuine delight. How are you? Very good to see you.

It was flattering to have the most celebrated man in the world call me by my first name with such seemingly spontaneous exuberance but, for the hour I spent with him, in the first interview he did with a foreign newspaper after assuming power, I chose to forget that Mandela, like that other master politician Bill Clinton, seemed able to recollect the name of virtually every person hed ever met. It was only later, when the glow of his charm had worn off, that I paused to consider whether his behavior was calculated, whether he had deliberately sought to beguile me, as he had succeeded in doing with every other journalist, every politician of every hue, practically every single person who had spent any time in his company. Was he an actor or was he sincere? Id come up with an answer in due time, but the honest truth is that, back then, I, like all the others, was powerless to resist.

Six foot tall, commandingly upright in a dark, pencil-sharp suit, Mandela walked a little rigidly, but his arms swung loose by his sides, his air both jaunty and majestic, as he led me into his wood-paneled officelarge enough to accommodate his old prison cell forty times over. The most urbane of hosts, he motioned me towards a set of chairs so finely upholstered that they would not have been out of place in the Palace of Versailles. Mandela, soon to turn seventy-six, was as gracefully at ease in his presidential role as if he had spent the past third of his life not in jail, but amidst the gilded trappings that his white predecessors had lavished on themselves to compensate for the indignity of knowing the rest of the world held them in contempt.

By a staggering turn of events, the man settling himself in his chair to face me had become quite possibly the most unanimously admired head of state in history. In truth, I was apprehensive. Wed met numerous times before. I had interviewed him; I had had plenty of chats with him, before and after press conferences and other public events since arriving in South Africa in January 1989, thirteen months before his release. Now, five and a half years later, on the morning of June 7, 1994, I felt intimidated. Before he had been a voteless freedom fighter, now he was an elected president. The great and the good had flocked from all over the world for his inauguration four weeks earlier here in these very Union Buildings, a vast brown pile perched on a hill above the South African capital that for eighty-four doleful years had been the seat of whites-only power. From this citadel, the apartheid laws had been enforced. From here, the chiefs of South Africas dominant white tribe, the Afrikaners, administered a system that denied 85 percent of the populationthose people born with dark skinany say in the affairs of their country: They could not vote; they were sent to inferior schools so they could not compete with whites in the workplace; they were told where they could and could not live and what hospitals, buses, trains, parks, beaches, public toilets, public telephones they could and could not use.

Apartheid amounted, as Mandela once described it, to a moral genocide: an attempt to exterminate an entire peoples self-respect. The United Nations called that a crime against humanity, but the former masters of the Union Buildings believed that they were doing Gods work on earth, and humanity be damned. With admirable logic, apartheids Calvinist orthodoxy preached that black and white souls inhabited separate heavens, rendering it morally imperative for the chosen few to respond to those who rose in opposition to Gods will with all the might that God in his bounty had awarded them. The ordinary black foot soldiers who rebelled were terrorized into submission, beaten by the police, sometimes tortured, in some cases assassinated, very often jailed without charge. The high-profile leaders, like Mandela, were punished with banishment to a barren island off the south Atlantic coast.

But Mandela endured and now, at last, he had stormed and taken the citadel. He never gloated in that hour we spent together, never came close to it, but the truth was that he had defeated apartheids God, had kicked the Afrikaner interpretation of Calvinist theology into the dustbin of history. The apartheid laws had been wiped off the books, democratic elections had taken place in his country for the first time and the party he led, the African National Congress, had won with two-thirds of the national vote. He was the chief now, the president on the hilltop. He had fulfilled his destiny and done so in classic style, playing the part of the hero who rebels against tyranny, endures prison with Spartan forbearance, rises again to liberate his chained people and, in a twist unique to Mandela, finally forgives and redeems his enemies. Little wonder the world regarded him as a giant. He, while never betraying any suggestion of arrogance or pomposity, was aware of the global esteem in which he was held. And he knew I knew.

Next page