PRESIDENTIAL DOODLES

TWO CENTURIES OF SCRIBBLES,

SCRATCHES, SQUIGGLES & SCRAWLS

FROM THE OVAL OFFICE

FROM THE CREATORS OF

CABINET MAGAZINE

TEXT AND INTRODUCTION BY DAVID GREENBERG

FOREWORD BY PAUL COLLINS

BASIC BOOKS

A MEMBER OF THE PERSEUS BOOKS GROUP

New York

Copyright 2006 by Immaterial Inc.

Text and Introduction copyright 2006 by David Greenberg

Foreword copyright 2006 by Paul Collins

Hardcover first published in 2006 by Basic Books,

Paperback first published in 2007 by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 100168810.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail .

Designed by Carole Goodman / Blue Anchor Design

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Hardcover: 13 ISBN 978-0465032662; 10 ISBN 0-465032664

Paperback: 13 ISBN 978-0465032679; 10 ISBN 0-465032672

eBook ISBN: 9780465003624

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

THERE ARE MANY THINGS THAT WE WOULD

THROW AWAY IF WE WERE NOT AFRAID THAT

OTHERS MIGHT PICK THEM UP

OSCAR WILDE

FOREWORD

DOODLER-IN-CHIEF

Decisions, decisions.

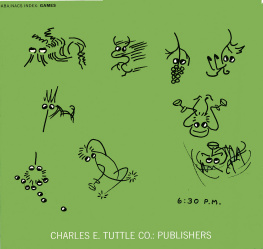

Decisions... decisions... decisions.

THE WORD IS WRITTEN SEVENTEEN TIMES OVER BY JOHN F. KENNEDYunderlined, boxed in, and crossed out as a reporter notedon a yellow legal pad in 1961, not long after he took office. Actually, the word is misspelled seventeen times over as decesions, but no matter... who would ever see it? Millions, as it turned out: In the wake of Kennedys assassination, a collection of his doodles, which included sailboats, underlined words, and overlapping boxes, went on a memorial tour of twenty-three cities in the summer of 1964. The exhibit attracted throngs of visitors; they solemnly filed past, eager to view the simple remains of a complex life.

It was not always thus; for although not impossible, one cannot very easily doodle with, say, a sharpened goose feather. Writing with a quill is a deliberative task. First, you must painstakingly cut your quill: take a sharp penknife and use its blade back to scrape the quills surface; and then, using the blade edge, cut a sharp, angled nib with a small and precise slit in the middle. A slip of the blade, and youll need to start all over againor, perhaps, get yourself a bandage. All this rather takes the fun out of scribbling googly-eyed faces, lazy spirals, and appallingly disproportionate dogs that sport gigantic rows of teeth.

And so you begin to see why there are not too many Founding Doodlers. Even a properly sharpened quill is damnably difficult to write with: it is inconsistent, it needs constant dipping, and it dulls quickly. The labor of quill writing meant that an eighteenth-century meeting required a secretary to take notes: others were not expected to trouble themselves with writing, and the secretary was certainly not allowed to doodle. Today, however, Washington teems with meetings at which every person in attendance has their own pen and paper. We can loop endless circles without spilling or running out of ink, indeed without looking down at what we are doing. Even this happy state of modern affairs couldnt always be taken for granted: back in 1959, the first American manufacturer of ballpoints found a public so wary that, to make the ultramodern device seem more reassuringly familiar, it had to disguise ball-points as pencils by encasing them in wood.

In fact, three things needed to happen before doodling could become, if not the Sport of Kings, at least the Fidget of Presidents. The first was the invention of the steel-nibbed pen. Like any terribly useful invention, nobody can quite agree on its origins. One of the earliest accounts places a steel pen in the hand of a certain Peregrine Williamson, a Baltimore jeweler in the first few years of the 1800s. Peregrine was terrible at cutting quills; in desperation, he contrived a sort of steel quill that would never need sharpening. He didnt keep his jerry-rigged contraption to himself for long, though: soon, he was making $600 a month from his invention. By 1823, the Englishman James Perry was mass-producing them, and a new generation of children learned to write with the newfangled metal quill. The Metallic pen is in the ascendant, and the glory of goosedom has departed forever, one textbook stated flatly.

But then theres the matter of paper. Paper was manufactured from old rags, and by the age of the steel pen, demand was outstripping the national supply of used underwear and grubby bonnets: paper was expensive, and not the sort of thing youd waste on aimless scribbles. Everything from hay to hemp was tried out as a substitute material, with mixed results at best. It took the German inventor Friedrich Keller, in 1843, to develop the first recognizably modern process for mass-producing paper out of ground wood pulp. The resulting product was easily shipped via burgeoning rail systems. Soon, paper was abundant; it was sold by the pad, the memo book, and the sheaf.

Writing itself became looser and more doodle-like. Itinerant penmanship instructors, often juggling other fashionable sidelines in daguerreotyping and cutting silhouettes, distinguished themselves in the mid-1800s with manuals featuring ever-more baroque swirls and flourishes, not to mention fanciful drawings of angels, birds, and grinning fish; indeed, the title page of at least one textbook is so covered with this calligraphic frippery that the words themselves are obliterated. But by the time of Abraham Lincoln, a generation of children had grown up with increasingly affordable pencils and steel pens. These youngsters practiced flourishes, repeated words over and over, and sketched out fanciful beasts in cheap notebooks and on the endpapers of Latin grammarsand, just as their schoolmasters had claimed, a few would grow up to be president.

Republicans are the greatest doodlers.

Now before any Democrat takes offense, it may console them to know that in nineteenth-century parlance a doodler was also a corrupt politician. But when it comes to conventional figurative drawing, Republican presidents do hold a clear lead: they can draw Tippy the Turtle, and they did draw the Pirate. Reagan often handed out his correspondence-course-style drawings as prizes at meetings; the Eisenhower administration was so fond of paint-by-numbers kits that an aide prodded the cabinet and visitors into creating a de facto White House gallery of kitsch. (The Eisenhower Librarys paint-by-the-numbers collection includes Swiss Village, painted by J. Edgar Hoover, and Old Mill, painted by Ethel Merman.) And Herbert Hoover was so well-known for his ornate geometrical patterns that autograph dealers were already scooping them up while he was still in office. In 1930, one collector even copied some of Hoovers patterns onto fabric and unveiled a line of Hoover Scribble Rompers for young children.