Eberts Bigger Little Movie Glossary copyright 1999 by Roger Ebert. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part

of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews.

Andrews McMeel Publishing, LLC

an Andrews McMeel Universal company

1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106

Mark ODonnells Laws of Cartoon Motion 1980

by Mark ODonnell. Reprinted by kind permission.

A Cynics Guide to the Language in Film Festival Catalog Descriptions, 1998, Toronto Globe and Mail

www.andrewsmcmeel.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

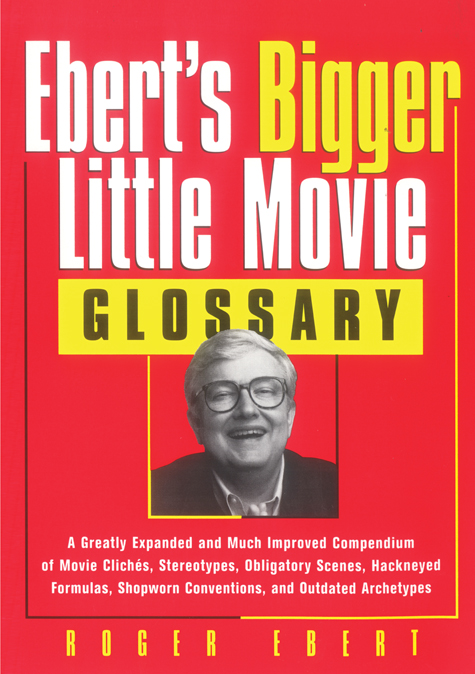

Eberts bigger little movie glossary : a greatly expanded and much improved compendium of movie clichs, stereotypes, obligatory scenes, hackneyed formulas, shopworn conventions, and outdated archetypes / [edited] by Roger Ebert.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-8362-8289-2 (paperback)

1. Motion picturesHumor. 2. Clichs in motion pictures.

I. Ebert, Roger. II. Title: Bigger little movie glossary.

PN1994.9.E19 1999

791.43'02'07dc21

v99-11008

CIP

Design by Holly Camerlinck

Composition by Kelly & Company, Lees Summit, Missouri

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND BUSINESSES

Andrews McMeel books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchase for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail the Andrews McMeel Publishing Special Sales Department:

Contents

Appendices

Things You Would Never Know

without the Movies

Mark ODonnells

Laws of Cartoon Motion

Greg Mattys

Creature Ferocity Index

A Cynics Guide to the Language

in Film Festival Catalog Descriptions

by Doug Saunders

Introduction

T he birth of the critical impulse comes in different ways to different people, and to some it comes not at all. Reconstructing my own development as a critic, I usually cite Dwight Macdonalds columns in Esquire as the key early influence. In the late 1950s and 1960s, Esquire was the best magazine in America, and I treated it like a road map to life. Macdonald was pointed, unforgiving, hard to please, and very funny.

But there was, I find, an even earlier influence. That would be Mad magazine, which had an almost incalculable effect on America in the 1950s. In the world of bland Eisenhower calm, there were whirlpools of satire: Mad, Bob and Ray, Stan Freberg, Lenny Bruce. I was going to the movies once or twice a week, and when I read the Mad satires of movies, I learned about clichs, stereotypes, obligatory scenes, standard dialogue, and preposterous plot developments. I began to apply what I learned to the movies I was seeing, and by the time I was in high school, that had become a habit.

Perhaps this Glossary grew out of those old issues of Mad. Years later, as a film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, I sat down at a typewriter and wrote down twenty or thirty glossary entries for a Sunday column. Why? It seemed like a good idea at the time. Recently Ive been scanning some of my earliest reviews into digital form, and in re-reading them, I find that I was forever pointing out the ways in which movies followed generic conventions, whether to honor or dishonor them. It seemed to be the way my mind worked.

The first column led to others. When I started publishing annual collections of reviews in 1986, a list of glossary entries appeared in each book. Readers started sending in contributions of their own. In 1991, my reviews and the glossary were picked up by CompuServe, and I was given a section of the ShowBiz Forum. Now a trickle became a flood (nice clich).

Eberts Little Movie Glossary was published in 1994, and also appeared in a British edition titled The Little Book of Hollywood Clichs. And I received still more submissions; I started using a new one every other week in my column The Movie Answer Man.

Now here is Eberts Bigger Little Movie Glossary. Its about twice the size of the first edition, although most of the earlier entries have been retained (I would not want to do without the Fruit Cart or the Talking Killer). About two-thirds of the entries are by readers, including some prolific ones. To them, my thanks.

The purpose of the book is to entertain, of course, but perhaps it might also shame filmmakers into avoiding the most shopworn conventions. The Fruit Cart syndrome has actually been satirized in more than one film, and I await the day when the Glossary itself is filmed. I imagine an entire film made of clichs, archetypes, and stereotypes; then I reflect that such a movie is released more or less weekly.

Will there be a third edition someday? Who knows? Contributions still flow in. You can mail them to me at the Sun-Times, 401 N. Wabash, Chicago 60610. Or E-mail me at 74774.2267@compuserve.com. New entries appear in the Answer Man column, which is syndicated to 305 papers and appears on-line on CompuServe, or at www.suntimes.com/ebert.

As this book went to press, I lost my friend and colleague Gene Siskel, who supplied some of these entries, and coined Siskels Test: Is this movie as interesting as a documentary of the same actors having lunch? Thats a question every filmmaker would be wise to ask before embarking on a new project.

Roger Ebert

Academy Mandate. The feeling by Oscar winners that an award for their film work is a validation of their personal beliefs. Examples: Vanessa Redgraves Zionist hoodlum speech; Oliver Stones insistence that his awards for Platoon were an antiVietnam War statement by the Academy; Richard Attenboroughs accepting the Oscar for Gandhi the movie on behalf of Gandhi the man; James Cameron asking for a moment of silence for the Titanic victims, etc.

Merwyn Grote, St. Louis

Accentuating Evil. The xenophobic and frequently anglophobic practice of defining villains by their distinctive accents, from twangy southern sheriffs to meticulously dictioned elitist snobs to wheezing Teutonic mad scientists. The hiring of British actors to play accented villains is particularly prevalent. Examples: Alec Guinness in Hitler: The Last Ten Days, Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man, Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove, Jeremy Irons in Reversal of Fortune, The Lion King, Die Hard 3, etc.

Merwsyn Grote, St. Louis

Acquariamcam. Underwater action scenes, even in the dirty waters of major ports, are always crystal clear, pristine, and well lit. Although characters are submerged longer than it would take me to get a popcorn refill, upon surfacing they start talking immediately.

Jim Carey, New Lenox, Ill.

Actress Inferior Position. In movie sex scenes, which are usually directed by men, the POV at the moment of climax is almost always the mans, so that we see the actress, not the actor, losing control.

Gene Siskel

AC-WAT-NOBI Movie. A Cop with a Theory No One Believes In.