Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Rachel Faugno

All rights reserved

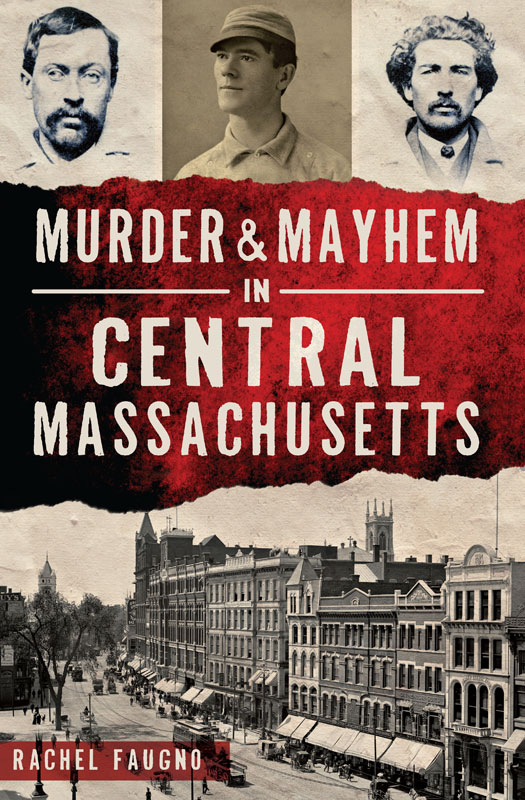

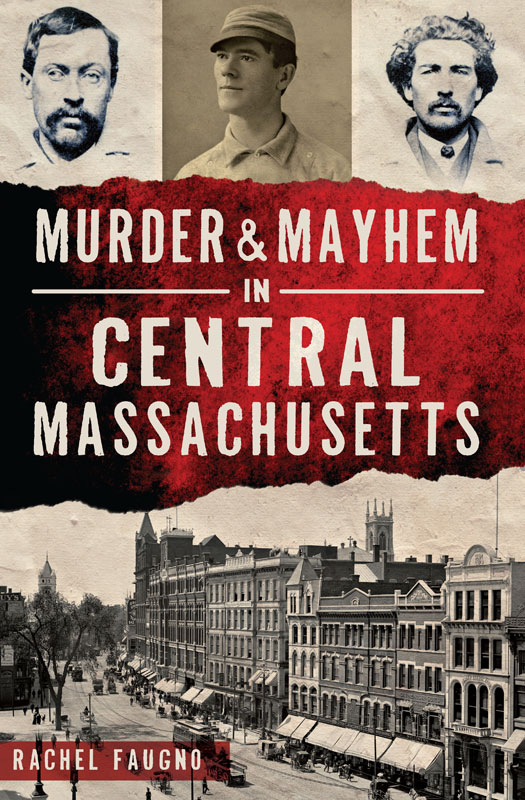

Front cover image of Main Street, Worcester, from LeBeau-Morrill Bullard Collection.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.672.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015958239

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.927.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Roger, back roads guide and history guru extraordinaire.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A great many people generously contributed their time, resources and knowledge to the creation of this book. I wish to give special thanks to Dennis LeBeau and Frank Morrill for providing photographs from their William S. Bullard collection of glass negatives from the late 1800s and early 1900s. Bullards remarkable photos help bring many of these stories to life.

I wish also to thank Brookfield historians Robert Wilder and Ronald Couture; New Braintree historian Connie Small; Barre Historical Society vice-president Margaret Marshall; Oakham Historical Association president Jeff Young; Brenda Metterville, director of the Merrick Public Library in Brookfield; Mary Baker-Wood, director of the Richard Sugden Public Library in Spencer; Roger Banks, Esq., who provided a copy of the Commonwealth v. Newell P. Sherman trial transcripts; Jaclyn Penny, Image, Rights and Design librarian at the American Antiquarian Society; Robyn Conroy, librarian at the Worcester Historical Museum; and all those who offered encouragement, input and suggestions throughout this project.

A heartfelt thanks to all.

INTRODUCTION

With its rolling hills, meandering waterways and sparkling ponds set amid lush and verdant woodlands, Worcester County in central Massachusetts presents a bucolic image. Its hard to imagine that anything truly awful has ever marred the seeming serenity of the sleepy old towns and historic city that occupy this pleasant landscape.

Yet from its earliest days as a colonial settlement right up to the present time, Worcester and its surrounding communities have been the scene of many violent and grisly crimes. Worcester itself was beset by violence from the start. The area was originally inhabited by members of the Nipmuc tribe, who called the region with its long, narrow pond Quinsigamond, which means pickerel fishing place. English settlers staked their claim to eight square miles of the land in 1674, but the settlement was burned to the ground on December 2, 1675, during King Philips War, a bloody conflict between Native Americans and English colonists that engulfed much of New England.

A second attempt at settlement was made in 1684, but the town was abandoned in 1702 during Queen Annes War when Native Americans again tried to reclaim their ancestral lands. When farmer Digory Sargent and his family refused to leave, he and his wife were slain.

Settlers claimed the land for a third time in 1713, changing the name Quinsigamond to Worcester, after the city of Worcester, England. The town became the county seat of the newly founded Worcester County in 1731, and the citizens erected their first courthouse in 1733. Eight years later, they witnessed the countys first murder trial.

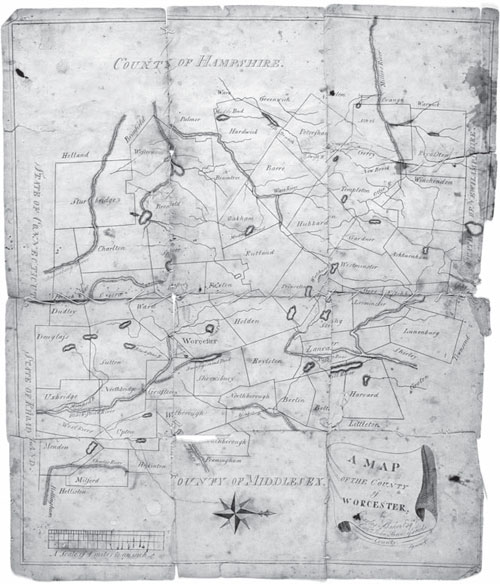

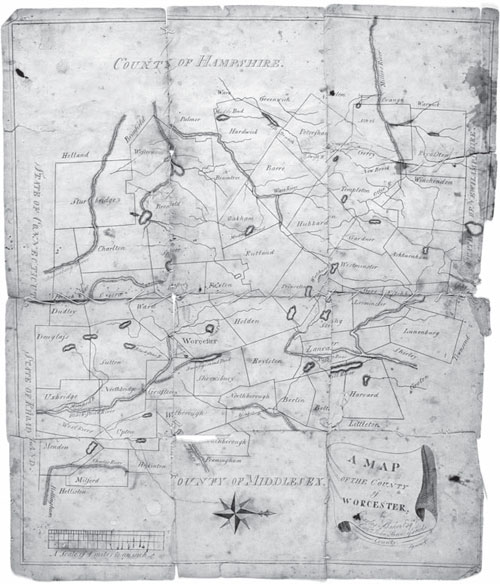

This map, published by Isaiah Thomas, shows Worcester County not long after it was established in 1731. American Antiquarian Society.

The murder occurred in Brookfield on September 29, 1741, during a husking bee on the farm of John Green, located midway on the present road from North Brookfield to West Brookfield. Greens son, Jabez, grew quarrelsome, boasting that he was ready to fight anyone and everyone who was present. In the ensuing excitement, he stabbed Thomas McCluer, who died of his wounds the following day. Green was arrested and conveyed to the Worcester jail, where he was held until the next term of the Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize and General Jail Delivery, in Worcester, on September 21, 1742. Twenty-three witnesses were examined, and the jury found him guilty. On October 21, 1742, Jabez Green was hanged for his crime.

Executions were public events in Worcesters early days, attracting huge crowds and creating a carnival-like atmosphere. The hanging of Samuel Frost on November 5, 1793, was said to have drawn two thousand spectators. Frost had been tried for murdering his father in April 1784 but was acquitted on the grounds of insanity. Records dont show whether he spent any time in confinement, but on July 16, 1793, he murdered his employer, Captain Elisha Allen of Princeton, during an argument in a field on Allens farm. Frost struck him more than fifteen times with the blade of a hoe and left his body lying on the ground. This time there was no acquittal. At the trial, he was found sane and sentenced to death.

Not everyone who was hanged in Worcester was convicted of murder. In fact, the first person to be formally executed in Worcester County was Hugh Henderson, who was hanged for the crime of burglary in 1737. Four other convicted thieves would follow. In all, seventeen men and one woman died on the gallows in Worcester. The last was Samuel J. Frost of Petersham, who murdered his brother-in-law, Frank P. Towne. The execution took place in the Summer Street jail on May 25, 1876. When the drop fell, Frosts head was nearly severed, and many of the witnesses fainted. After that, execution became a function of the state.

In cases where the death penalty wasnt applied, other penalties were meted out. One popular punishment was to sentence a wrongdoer to sit for hours on the gallows with a noose around his neck before being hauled off to jail. Other offenders might be sent to the pillory or whipping post, have their forehead branded or an ear cropped or be sold into bondage.

Early records show that Caleb Jephterson was sentenced to the pillory for an hour and a half for the odious and detestable crime of blasphemy. Another man, James Trask, was convicted of fraud and sent to the pillory for one hour, whipped thirty stripes and then, because he was unable to pay a substantial fine, sold into bondage for four years.

In 1790, Revolutionary War hero Colonel Timothy Bigelow was thrown into the old stone jail on Lincoln Street in Worcester for nonpayment of a debt. The jailers well-worn ledger reads, Colonel Timothy Bigelow: Committed February 15Discharged by Death April 1, 1790. Colonel Bigelows fate is a reminder that life in the good old days was often hard and justice harsh. Although it is tempting to regard the past nostalgically to imagine a simpler time when people were happier, kinder or more good hearted than they are todaydishonesty, conflict and violence have always been with us. Our definition of crime and methods of punishment change with the times. The scales of justice tilt alternately toward severity or leniency.

Next page