Princess of the Hither Isles

Princess of the Hither Isles

A Black Suffragists Story from the Jim Crow South

Adele Logan Alexander

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of

Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2019 by Adele Logan Alexander.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Race, copyright 2001 by Elizabeth Alexander, reprinted from Antebellum Dream Book, with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org.

Set in Monotype Bulmer type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019935203

ISBN 978-0-300-24260-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For those who preceded, accompanied, and sustained me, who are wiser, braver, and kinder than I, and whom Ive most admired and loved

Contents

Princess of the Hither Isles

INTRODUCTION

Legacies

IN 1983, MS. MAGAZINE PUBLISHED AN article Id submitted about finding my paternal grandmother, who was a pioneer in the woman suffrage movement. The editors said this: Adele Logan Alexander is working on a book-length biography of Adella Hunt Logan. Since then, Ive written many other things, taught history, acquired a headful of gray (I like to think silver) hair and a glorious rainbow of grandchildren. But I continued pursuing that intriguing political activist, that little-known, outspoken black woman who looked white, for whom I was named.

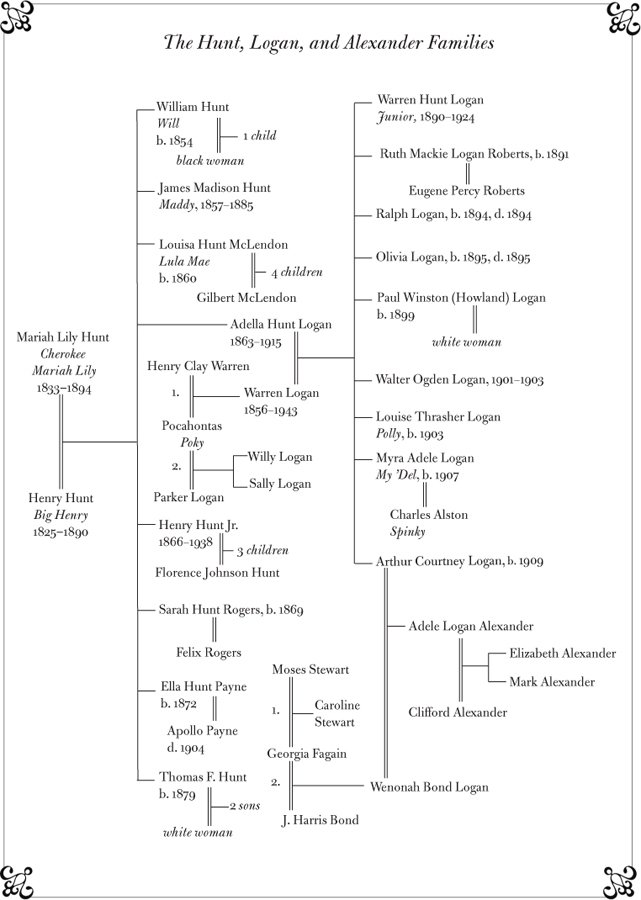

I learned about Adella and more about our countrys grievous war during which she was born and the next half century in the southern United States. I explored relationships among her kin, as well as theirs with both obscure and renowned figures of that era. Among them, my relatives talked about the fellow they admired, respected, and often saw in New York City but called Dr. Dubious; another, the brilliant scientist whom they warmly referred to as Uncle Fess Carver; and the familys Alabama neighbors, the Great Man, Booker T. Washington, and his obdurate spouse. There was a long-gone President Roosevelt too, not the Democrat who in my childhood I thought always had and always would hold that omnipotent position but an earlier one, a Republican, whom my grandfather Warren Logan seemed to have known rather well. Ultimately, I also realized that my grandmother Adella Hunt Logans legacy as she worked to acquire the vote for women was her way of trying to give them a voice, of empowering them.

And looming over their lives was Jim Crow, the ugly nemesis whom they scorned, defied, and struggled to outsmart.

My father and aunts often reminisced about Tuskegee, a fabled place sometimes called the Hither Isles, which they both loved and loathed, and about Atlanta University, where most of them had attended school. And before those venues, I learned, there was Sparta, Georgia.

I slogged through versions of Adellas story that were conventional history and other fictionalized ones but ultimately determined that this should be neither a traditional biography nor a novel. Rather, its an intricate memoir about an era, places, and mostly a woman to whom Im irrevocably bound. Here Ive tried to reveal and reconstruct Adella from a plethora of archival and published materials but more through what my family and others boldly trumpeted, whispered, or surreptitiously confessed. To do that, Ive unraveled many snarled threads, spun them out again to weave into a comprehensible whole the often perplexing documentation that I accumulated. Ive speculated about how and why results that I know for certain might have come about and tried to understand and interpret the incredible accounts that I heard and believed over the years but cant incontrovertibly prove.

Some of Adellas stories were inspiring; others were almost too painful to retell.

As I position my grandmother in her world, Im reminded of phrases we hear and voice today: Black Lives Matter, Equal pay for equal work, My body, my choice, Votes for all, and #MeToo. The times, words, and players change; the issues and their urgency do not.

I grew up in a family whose members proudly considered and spoke of themselves as Negroes. They healed, taught, and counseled Our People, identified with and staunchly defended the race, never boasted of their Native American or white blood, but were mostly blue-, green-, or hazel-eyed and paler skinned, narrower featured, and straighter haired than many of my Jewish friends at school and my diverse, upper-Manhattan neighborhoods Italian American cobblers and greengrocers. And those relatives who looked white all had darker-skinned spouses. It didnt seem unusual to me. Thats just how my world was populated.

I also heard about my fathers mystery uncle Thomas Hunt (he roared with laughter about having an Uncle Tom), whod disappeared in California, where he saw his even whiter-looking but black-identified sister Sarah by appointment only. And once a year, my own uncle Paul came from way out west to visit us. Even as a child, I sensed that his siblings loved, disdained, and mistrusted him in roughly equal parts. Living in the Big Apple, I surely knew no one else whose uncle was a forester and lived in Oregon: a faraway, mythical realm.

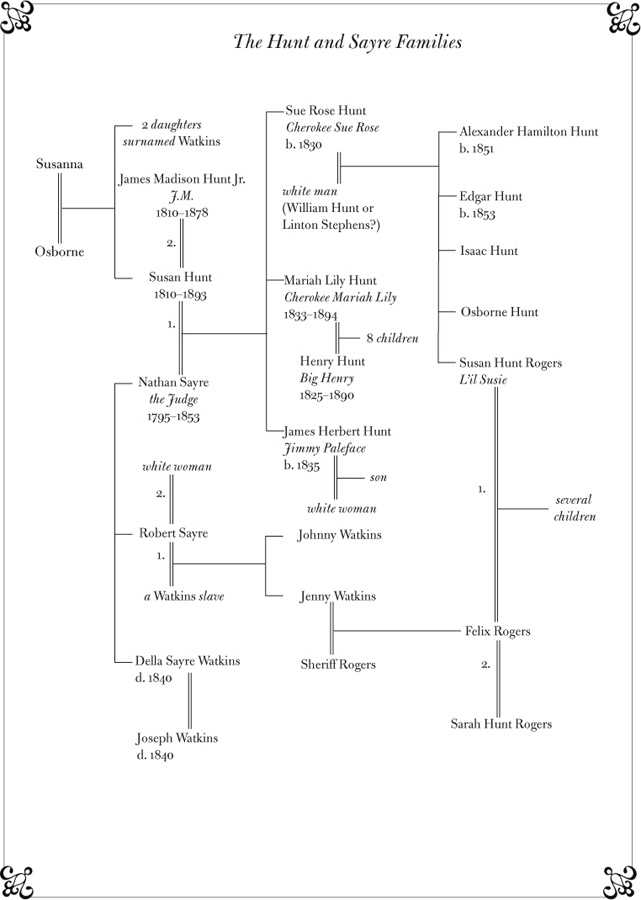

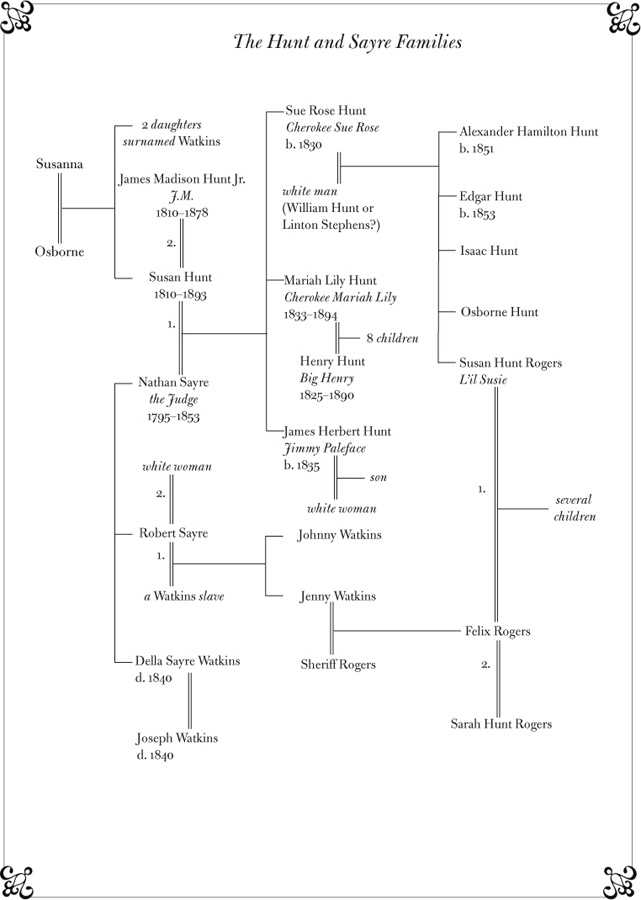

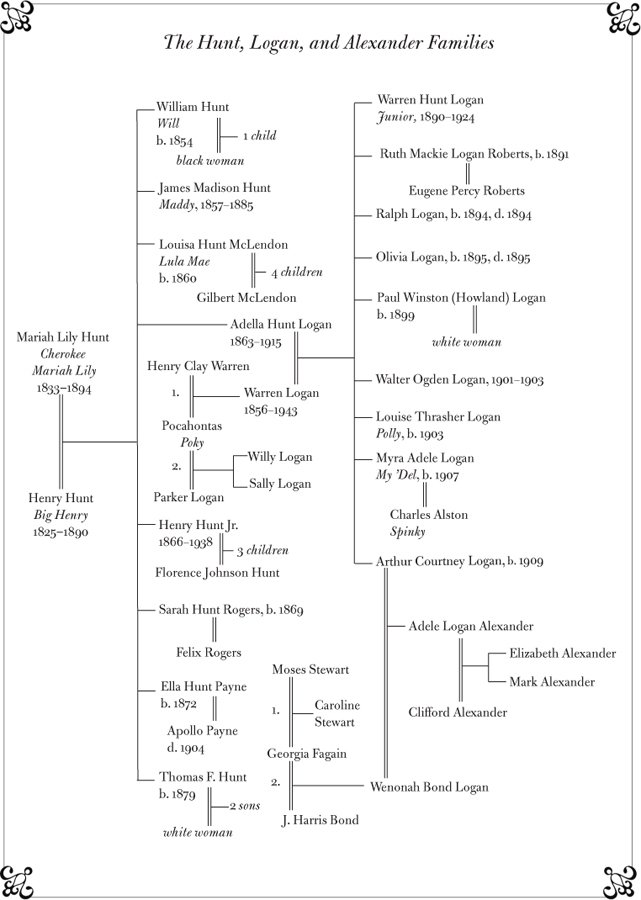

In past generations, I learned, there had been other legendary relatives: someone called Judge Sayre; his wife, Susan Hunt (one of my great-great-grandmothers); and their daughter, known as Cherokee Mariahher name pronounced with a long i and spelled with an h.

During my earliest years, a pale and frail old man whom my father and his sisters called Dad came north every December. Only once, however, did he bring along his wife, about whom my aunts hissed, Shes not your grandmother! Georgia is. I already knew that Georgia Stewart Bond, who often lived with us, was my mothers mother and my beloved Nana. But that other woman, that unwelcome visitor, they confided, was the wicked witch whod long ago exiled my then eight-year-old father from his Alabama home.

Georgia Bonds older daughter, my maternal aunt Caroline Bond Day, had written an awesome tome, which was our familys secular Bible. Titled A Study of Some Negro-White Families in the United States, it began as her Harvard-Radcliffe masters thesis in anthropology. Its filled with photographs, among many others, of various Sayres, Hunts, Logans, and Bonds. Arcane designations, 1/4 N, 3/4 W, 1/8 N, 1/8 I, 3/4 W, even 4/4 W, appear below them. Interracial hybridity, Carrie had demonstrated in the 1920s, wasnt something that suddenly would make its disquieting appearance in the late twentieth century. Rather, it was and is a phenomenon bred deep in the American bone, sometimes accompanied by dire warnings from fearful or angry white folks about the threat of mongrelization. Recent scientific advances and knowledge about DNA have complicated but also confirmed this old-but-new phenomenon. We need to better understand the similarities with and differences between the children of our recent, post

Next page