stolen glimpses

captive shadows

ALSO BY

GEOFFREY OBRIEN

PROSE

Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir

Dream Time: Chapters from the Sixties

The Phantom Empire

The Times Square Story

Bardic Deadlines: Reviewing Poetry, 198495

The Browsers Ecstasy: A Meditation on Reading

Castaways of the Image Planet: Movies, Show Business, Public Spectacle

Sonata for Jukebox: An Autobiography of My Ears

The Fall of the House of Walworth: A Tale of Madness and Murder in Gilded Age America

POETRY

A Book of Maps

The Hudson Mystery

Floating City: Selected Poems, 19781995

A View of Buildings and Water

Red Sky Caf

Early Autumn

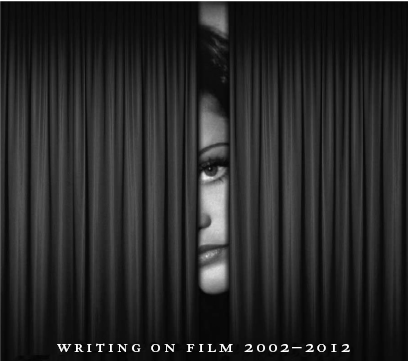

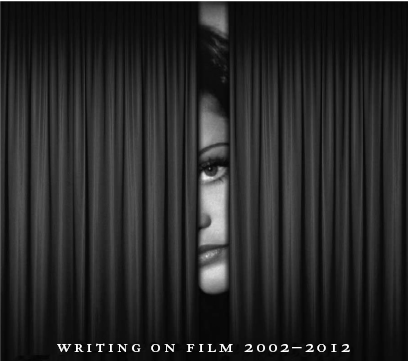

stolen glimpses

captive shadows

GEOFFREY OBRIEN

COUNTERPOINT | BERKELEY

Stolen Glimpses, Captive Shadows:

Writing on Film, 20022012

Copyright Geoffrey OBrien 2013

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

OBrien, Geoffrey, 1948-

[Essays. Selections]

Stolen glimpses, captive shadows : writing on film, 2002-2012 / Geoffrey OBrien.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61902-222-5

1. Motion pictures. I. Title.

PN1994.O28 2013

791.43dc23

2013002370

Cover design by Michael Kellner

Interior design by Neuwirth & Associates

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Robert Silvers

contents

(Sam Raimis Spider-Man)

(Eric Rohmers The Lady and the Duke)

(Steven Spielbergs Minority Report)

(Fritz Lang)

(Jacques Tourneur)

(Quentin Tarantinos Kill Bill: Vol. 1)

(Mel Gibsons The Passion of the Christ)

(Michael Moores Fahrenheit 9/11)

(Cary Grant)

(Jacques Beckers Touchez pas au grisbi)

(Kihachi Okamotos The Sword of Doom)

(Steven Spielbergs War of the Worlds)

(John Fords Young Mr. Lincoln)

(Val Lewton)

(Carol Reeds The Fallen Idol)

(Alfred Hitchcocks The Lady Vanishes)

(Edgar Ulmers Detour)

(David Chases The Sopranos)

(Akira Kurosawas High and Low)

(Magnificent Obsession by John Stahl and Douglas Sirk)

(Eric Rohmers The Romance of Astrea and Celadon)

(John Fords The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance)

(Frederick Wiseman)

(Jean-Luc Godards Breathless)

(Josef von Sternbergs Underworld)

(Leo McCareys Make Way for Tomorrow)

(Jean Cocteaus Beauty and the Beast)

(Terrence Malicks The Tree of Life)

(Olivier Assayass Summer Hours)

(Michel Hazanaviciuss The Artist, Martin Scorseses Hugo, Victor Sjstrms The Phantom Carriage)

(Benh Zeitlins Beasts of the Southern Wild, Wes Andersons Moonrise Kingdom)

(Paul Thomas Andersons The Master)

MOVIES WERE A RECENT INVENTION, and now they are mutating into some further, indeterminable identity: a transient episode in what is after all nothing but the history of transience. The machinery for preserving moments, a triumph of nineteenth-century scientific ambition, was itself to be only of a certain moment. It is impossible to foresee in what form its archive will be preserved, if at all, or whether most of it will join the eroded cave paintings, shredded tapestries, and burnt icons in the great museum of oblivion.

Before the machinery was movies it took other forms: daguerreotypes, flickering mobile toys, or stereoscopic projections like those that Ralph Waldo Emerson saw in Concord, Massachusetts, on November 14, 1860, taking them as an almost unsurpassable display of technical advancement: Yesterday eve I attended at the Lyceum in the Town Hall the Exhibition of Stereoscopic views magnified on the wall, which seems to me the last & most important application of this wonderful art: for here was London, Paris, Switzerland, Spain, &, at last, Egypt, brought visibly & accurately to Concord, for authentic examination by women & children, who had never left their state. Emerson ends his account with a sentence that I take as an early and prescient instance of American film writing: And the lovely manner in which one picture was changed for another beat the faculty of dreaming. A little over half a century later the world would indeed be dotted with dream palaces. And less than a century after that the visions that filled those palaces would shrink to the size of a screen held in the palm of the hand. Its as if the cities themselves had disappeared into those miniature screens.

It is easy to lose sight of how strange it all is, a breaching of barriers so thoroughly assimilated that those who came beforethe earlier generations who managed to live without photography or sound recording or simultaneous broadcastseem stunted beings who lacked a fundamental part of their sensory apparatus. But cinema, just for having been around a while, doesnt get any less strange, or any less powerful. To remember the strangeness is perhaps a way of keeping the power under some sort of manageable control, lest we be altogether overwhelmed by shadows.

The mere fact that a movie can exist is a more astonishing fact than the qualities of any given movie, just as the existence of language is more astonishing than any poem. There was always something so implausible about this invention as to fall necessarily under suspicion. This was smugglers booty. The heavy metal cans contained stolen glimpses of other worlds. To hang suspended in air, see through walls, fly over cities and peer unseen at their inhabitants, go back in time: these must be in some sense illicit pleasures. Movies are the banal miracle, an achieved magic to which we have almost become inured.

What interests and unsettles is that almost: that troubling margin of unease with what takes place when I watch an old film. Have we really internalized once and for all the fact that we can do this? Forget for a moment about art or history or distraction or other such alibis. There are other names for the temptation to which I have so often yielded. I possess a machine that permits time travel.

There are limits to its capacities. I can move backward but never forward. My role does not go beyond spying on the inhabitants of other moments and surveying as much as I can of their domain. But its as easy as pushing open an unlatched screen door. I want to go there not because its imaginary but because its real. Odysseus and Aeneas had to cross the River Styx to gaze on the dead, I can do it as much as I please to the point of indifference: watch them walk, laugh at their jokes, perk up at the rhythms of their dancing.

A CAVE PAINTING, it might be argued, is no less strange, or an alphabet. It is unnervingly odd, at bottom, to inhabit ancient sentences. The mere sight of a black stone cup that quenched neolithic thirst might well set off tremors of alarm about the time through which we so heedlessly pass. Yet every form, every image, every sentence ever made was made to tamp down any such alarm by marking a point in time to which one could return at will. A physical object was not even required. From memory alone the shape or phrase could be reconstituted just as it was.