Contents

Guide

In loving memory of my parents,

Gordon Norman Gilchrist and

Mary Margaret (ne Heseltine) Gilchrist

CONTENTS

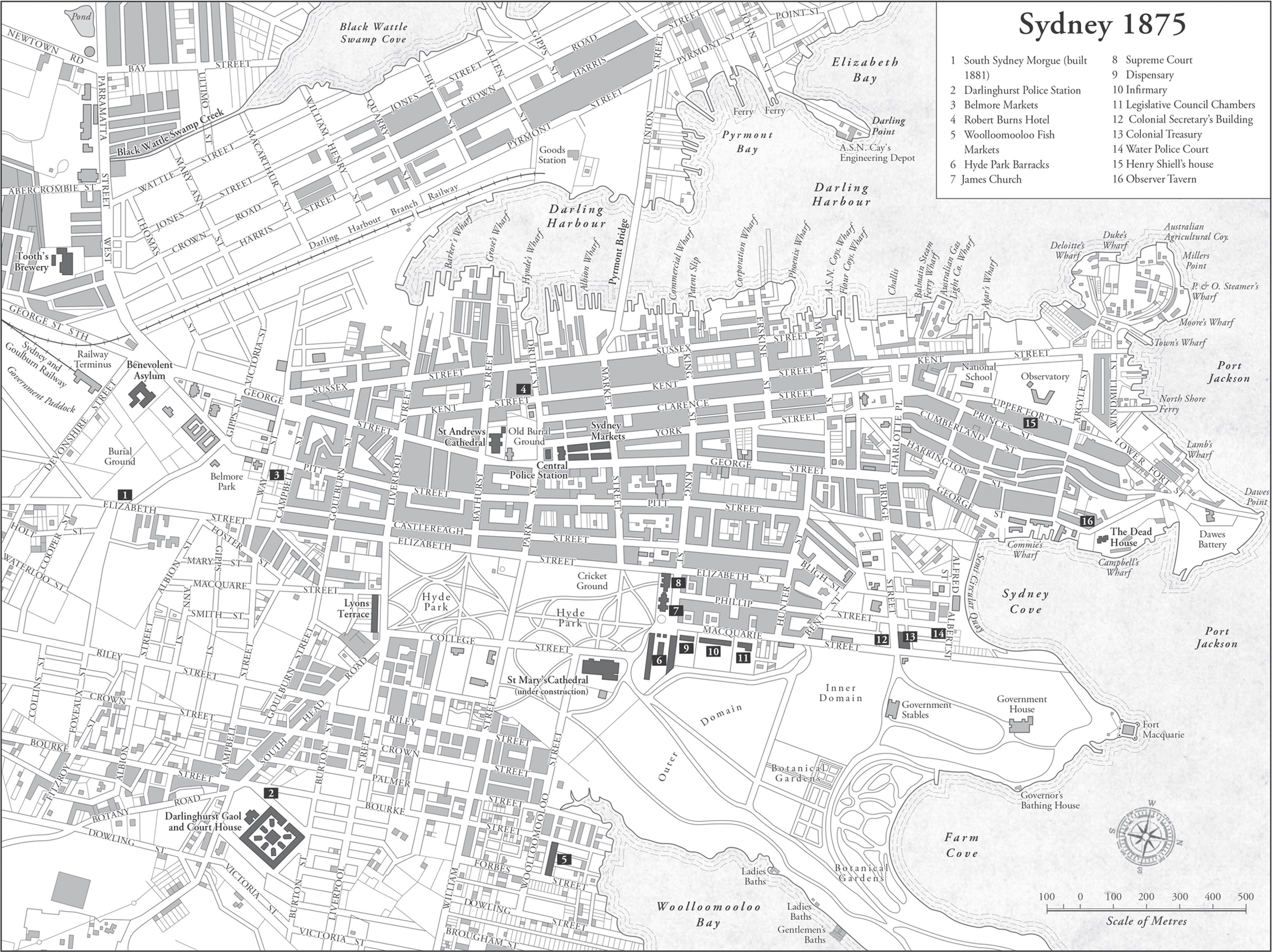

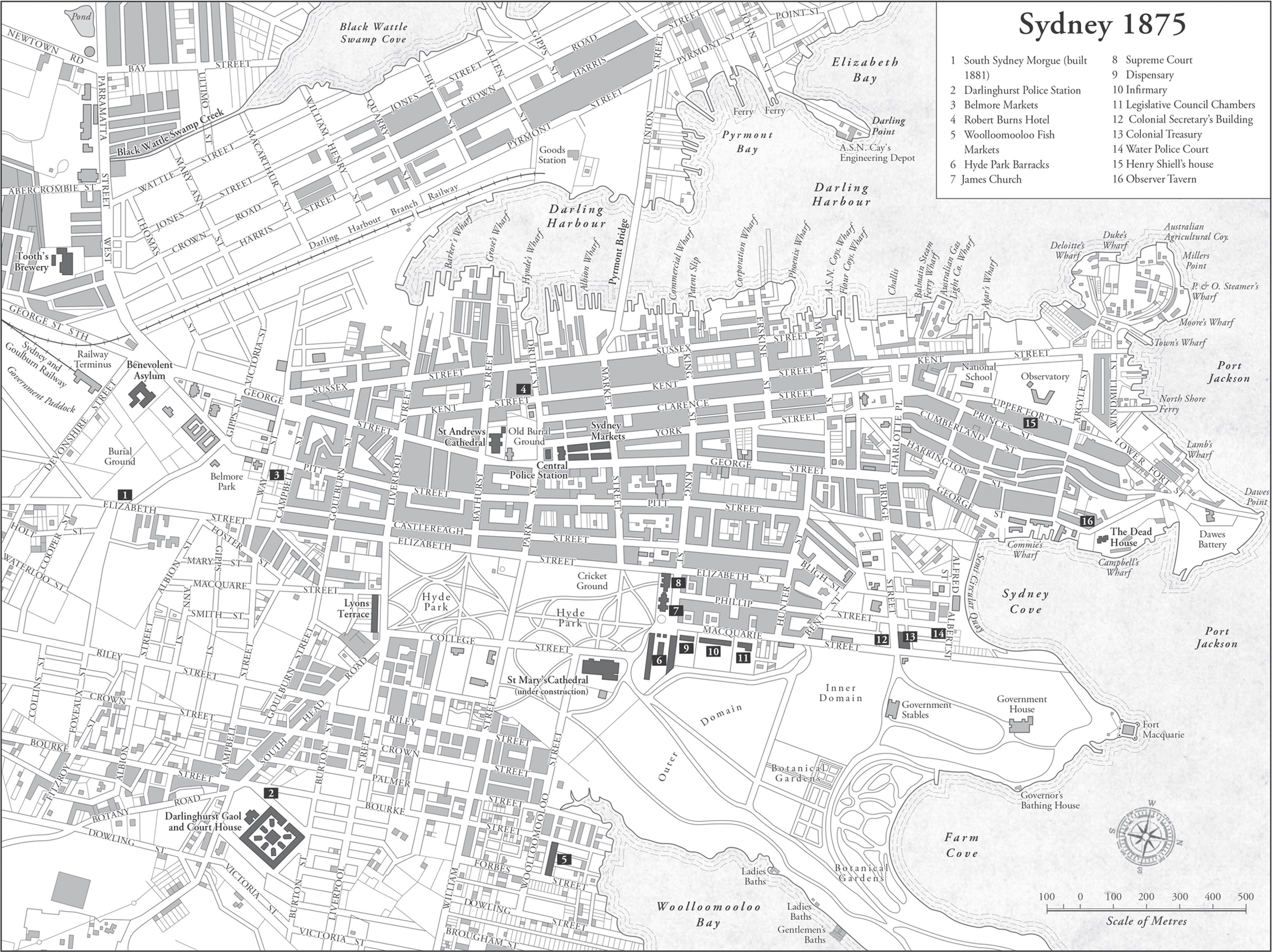

M onday, 27 August 1866 had been a very busy day and Henry Shiell was utterly exhausted. Just six weeks into his new job, he wondered if his position as the Sydney coroner was always going to be quite so demanding. At nine oclock that morning he had resumed an adjourned inquest at the Hand of Friendship Hotel on Bathurst Street. Mary Ann Peard, who was just five years and five months old, had suddenly died following a convulsive fit. Dr William Bell conducted a postmortem and the inquest concluded that the cause of death was convulsions brought about by a diseased brain. From here Mr Shiell quickly strolled across Hyde Park and returned to his small office near the old barrack building on Macquarie Street. Here, at his second inquest of the day, the sudden death of John Tarbuck was being investigated. Tarbuck had fallen nine feet off a ladder while painting the inside of Chalmers Church in Cleveland Paddocks. At the time, he had merely broken his right elbow joint. However, on being conveyed to the Sydney Infirmary, he became delirious and suddenly expired. Dr Charles McKays post mortem revealed that he had died from extensive disease of the heart, aged just thirty-three years.

The coroner was soon afterwards making his way towards Chippendale. Here at the Royal Oak Hotel an inquest into the death of Charlotte Cain McElroy had been convened. Only eight weeks old, the illegitimate child had been ailing from birth and had died on Saturday afternoon. Emaciated and badly nourished, a verdict of died from natural causes was recorded. From here, Mr Shiell hurriedly headed towards Newtown. At the Daniel Lambert Hotel, a jury of twelve heard that Korah Chadwick had died at his residence on Missenden Road the day before. Consumption had ravaged the Californian for years and he had been addicted to chlorodyne to relieve his pain. Like Tarbuck, Chadwick was also thirty-three years of age. Dr William G. Sedgwick was of the opinion that he had died from disease of the lungs. Despite this, the gentlemen of the jury returned the general, vague and frequent verdict of died from natural causes. This finding had recently replaced the more religiously inclined, died from the visitation of God. Neither were of much value to the statistician or the compiler of morbidity and mortality rates, either at the time, or indeed since.

Mr Shiells final case that day was at the Newtown Inn on Newtown Road. George Francis Prattley aged four years and ten months had been badly burnt the previous morning when his clothes accidently caught alight from the open fire in the kitchen of his parents house in St Peters. He died soon afterwards. Dr Sedgwick suggested that he had died from shock to the system in consequence of the burns he had received. The gentlemen of the jury concurred, and the cause of death was officially recorded.

Investigating the sudden deaths of an infant, two young children and two adult males was all in a days work for the city coroner. To be sure, that day in August was a particularly busy one. Some days there would be no inquest, however the coroner was always on call, day and night. His role was to inquire into deaths that were strange sudden or suspicious, violent or unnatural. All such deaths in gaols, asylums and hospitals were to be reported to the coroner, and since 1861, the origins of suspect building fires also came under his remit.

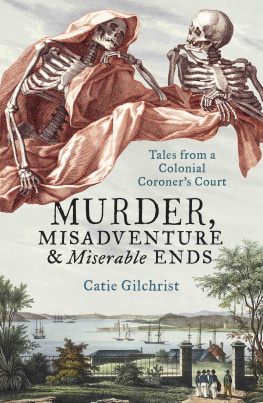

Henry Shiell was the coroner for metropolitan Sydney between July 1866 and January 1889. This book is about the inquests that were held during his long career. Australian historians have not used coroners inquests in a detailed or systematic manner, and yet they offer a rich insight into life and death in the colonial city. The tragic paper trails they have left behind, construct detailed obituaries, with every inquest recording the name, age, sex, country of origin, occupation, place and cause of death. The witnesses and neighbours who attended the inquest often revealed the sad and the mundane, but also the vivid drama of daily life. How normal, everyday folk died, often reflected how they had lived. The inquest records allow us to peer into households and workplaces, and take a peak inside private lives that would otherwise remain unknown.

In the nineteenth century, death was very much a part of daily life in Sydney. People were often found dead in the street, expired in a park or drowned in the harbour. And death investigation was a thoroughly civic affair because the inquest itself was an open public spectacle. Inquests were usually held in hotels and taverns. The dead body would be laid out for the coroner, a jury of twelve good and lawful men and any number of witnesses to inspect. Indeed, the body of the deceased had to be viewed by the jury to legally validate the inquest. The opinion of a qualified medical doctor was always given and a post mortem was carried out when the cause of death was not plainly manifest. There was then, a close entanglement between medicine and the practise of the law, even before the development of modern day forensic science. After listening to witnesses, family, friends and the medical evidence, the coroner would sum up the facts, and the jury would return a majority verdict on how the death had been caused. This was recorded on an inquisition form and signed by the jurors and the coroner.

The right to attend, bear witness, serve on a jury or simply watch an inquest had long been regarded as a birthright dear to the hearts of Englishmen. (Today the public is still permitted to sit in on an inquest in New South Wales.) This was because the essence of inquest practice was public participation and assent.

The inquest itself was a fact-finding investigation rather than a trial, an inquisitorial rather than an accusatorial procedure. Deaths recorded by the coroner as having been caused by murder or manslaughter were not necessarily verdicts that were later upheld in the law courts. The coroner in such cases was empowered to grant bail, or order a murder suspect into police custody to await their trial. Some deaths investigated by the city coroner were indeed criminal, although murder was surprisingly infrequent in colonial Sydney. This meant homicide was spectacularly sensational when it did occur. Manslaughter as a cause of death was more common, either through accident or drunken violence. Fistfights and heads hitting kerbstones after a single blow on occasion led to an untimely death, and both men and women died in drunken brawls. Inquests into drink related deaths regularly led to calls from the wowsers and the Mrs Grundys of the day for much stricter licensing laws. And in the nineteenth century, a thriving temperance movement emerged out of the supposed crisis of the demon drink.

Then, as now, the city coroner held inquests into deaths caused by domestic violence and incidents of murdersuicide. Suicide too was a common cause of death in colonial Sydney. For men, pecuniary disgrace, disruption of personal attachments or matters of honour sometimes led to the rash act. For women, it was usually the tragic outcome of youthful heartbreak or undiagnosed post-natal depression. Many suicides were simply mentally unwell and had evaded the watchful eye of the colonys lunatic asylums. And despite the old adage, the past is not always a foreign country. The living desire to die, sadly endures. Suicide and depression still plague Australian society.

Next page