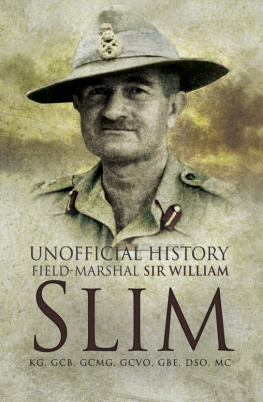

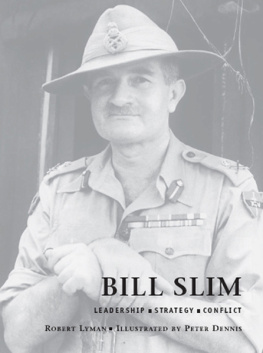

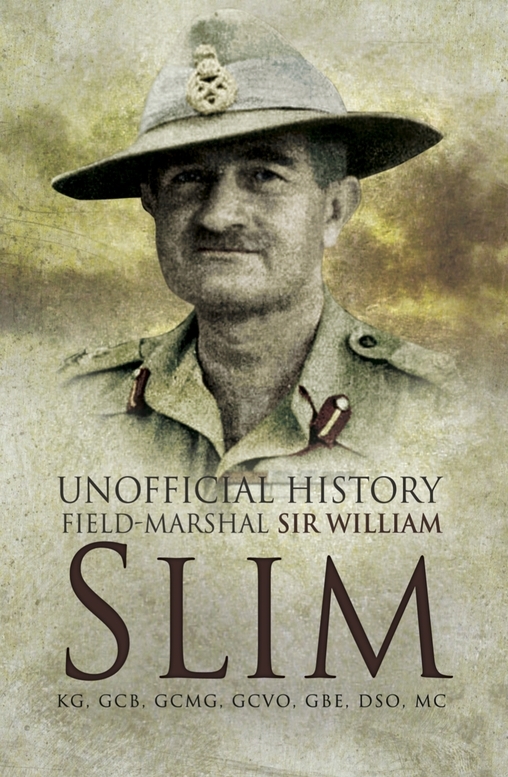

William Slim - Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim

Here you can read online William Slim - Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Pen & Sword Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim

- Author:

- Publisher:Pen & Sword Books

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also by the same author

Defeat into Victory

Courage and other Broadcasts

Contact with the enemy which had been lost for some hours had been established about half an hour earlier, but little opposition was encountered until 4 p.m., when the vanguard was checked by the enemyapparently his rear-guardholding a line of trenches which ran north-east from Um-ul-Baqq for about two and a half miles.

British Official History of the War: Mesopotamia

S OME years ago I found myself, with half an hour to wait, in the library of a great government department. My eye wandered over the shelves seeking a book to while away the time, but ponderous tomes on international law and economics have never attracted me. I was just going to ask the librarian for the unexpurgated Arabian Nights that I know he keeps tucked away on some discreet shelf, when I caught sight of a long row of red volumes. They stood in ordered ranks, uniform and soldierly: the British Official History of the War.

The Campaign in France and Flanders? No, I went to France with the Conscientious Objectors. You might write a book about that extraordinary collection of exhibitionism, idealism, courage and cold feet, but not an Official History. I doubted if the noncombatant corps would be mentioned, and I was after something personal, something I had seen myself. Gallipoli? No, the Peninsula held memories I was in no mood for now. Mesopotamia ? Why, yes, I would dip into that. Not the cruel battles before Kut, but some lesser action that I could look back on with a smile instead of with an ache for lost friends. Say the capture of Um-ul-Baqq on the dusty Tigris bank. There would not be a long account, enough for a quarter of an hour or so, but my battalion would be thereI might even find my own name. It would be very satisfying to find oneself a bit of official history.

I pulled out the volume, sank into an armchair, and, thanks to the admirable system of dates in the margin of every page, soon found the place I wanted. I glanced at my watchI could not afford to miss that appointmentand settled down to read.

Contact with the enemy which had been lost for some hours had been established about half an hour earlier, but little opposition was encountered until 4 p.m., when the vanguard was checked by the enemyapparently his rear-guardholding a line of trenches which ran north-east from Umul-Baqq for about two and a half miles.

And that was all! Um-ul-Baqq, the only battle I ever, up to that time, enjoyed, dismissed in those few lines. Scandalous! know Um-ul-Baqq was not one of the seven, or should it be seventy, decisive battles of the world, but.... It was very quiet in that library. I rested the open book on my knee and slipped back through the years.

I do not believe Napoleon himself ever felt so Napoleonic as I did that early spring morning in 1917 when I watched the first mixed force I had ever commanded defile before me. The khaki-clad British infantry trudged past, two companies of them, with a grin and a joke, as they have trudged across history. After them came a section of machine-guns on pack, with here and there a bobbish mule swinging sideways from the ranks; and then, O pride of a subalterns heart, two jingling, rattling, rumbling 18-pounders!

I was happy. We were winning; the fatality that had hung like a pall over Mesopotamia had lifted at last. The Turk was on the run, and we were after him. The men sang as they marchedand they had not done that for a year. On the other bank of the great mud-coloured Tigris the dust-storms of the night still hung menacingly, but on ours the cool dawn breeze that came rippling across the dead flat plain raised no dun clouds between us and the pearly horizon. It was like sunrise at sea; it woke you up and put you on your toes. I suppose if I had been one of those wartime subalterns who have since written so prolifically and pathologically of their reactions to such scenes, I should have psycho-analysed myself into a desperate gloom, swallowed half a bottle of whisky, and laughed bitterly. But I had never heard of psychoanalysis, I had not seen whisky for a fortnight, and if I laughed it was from anything but bitterness.

I watched the tail of my little columnsome stretcher-bearers from the field ambulancego past, and then cantered to the front. We were just approaching a cutting which led steeply down to a pontoon bridge across a hundred yards wide tributary of the Tigris. This bridge had been completed under fire the previous night; it looked none too secure, and the sappers were still busy on it. Their officer asked me to send the men across in parties as the current was strong. No engineer will ever admit a bridge he has built might break, but there was a look in that sappers eye which warned me that the less weight we put on his bridge the better.

I dismounted and led my horse, Anzac; he came quietly enough, snorting a little as the loose boards moved under his feet and the pontoons swayed to the rush of water. Infantry, by sections, came over all right, and only one machine-gun mule played the fool. At one time it certainly looked as if he, his load, and the three men clinging to him would all go overboard together. However, being a mule, and therefore full of common sense, he realized that if he did it would be the end of him; so he gave a final shake that nearly rattled his load off, and minced demurely across. The guns gave more trouble. They and the limbers skidded down the slope with locked wheels on to the bridge. The horses hated the dip and swing of the pontoons as the weight came on them, but after some hair-raising moments all were over and the column halted to close up on the far bank.

The colonel rode across the bridge and gave me my final instructions. My little force was the vanguard to the advance on the Tigris east bank. The Turks, so the aeroplanes had reported, were digging hard on a line running back from the river at the village of Um-ul-Baqq, several miles ahead. I was to shove on for Um-ul-Baqq, clear away any opposition and, if possible, seize the village itself There followed some brief directions about casualties, replenishment of ammunition, and sending back information. And, concluded the colonel, fixing me with a steady eye, and remember the first duty of an advance-guard is to advance!

Rather sobered by this grim injunction, I called up my officers. They stood in a semi-circle before me. It was a young mans war, at least the fighting of it was, and, with one exception, we were all in the early twenties. The exception was the gunner, and he looked strangely out of place among us, with the big grizzled moustache of the old regular soldier, and a face like Fochs. He had a single star on his shoulder, but battery sergeant-major all over him.

I had not much to give them in the way of orders, but I repeated what the colonel had told me. And, I ended, trying to look as much like him as I could, though in that nature gave me little help, and remember, the first duty of an advance-guard is to advance! It went very well, I thought, and they all seemed rather impressed.

Five minutes later we were off, a line of scouts ahead, the platoons of A Company in blobs behind them, then my own B Company, with the machine-guns on the leeward flank to save us from dust, and last of all the 18-pounders. Turning in my saddle, I could see dust clouds beginning to rise far behind, and knew the main body was on the move. Although we were near the Tigris, the bund, an earthwork embankment, hid it from us, and it was only in the distance that we could follow its course by dark masses of palm groves and gardens. For the rest, the country was as flat as a table and bare to the horizon, now drawing nearer as the dust haze increased.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

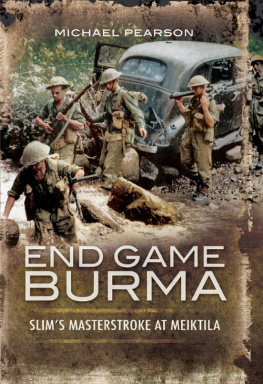

Similar books «Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim»

Look at similar books to Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Unofficial History: Field-Marshal Sir Williams Slim and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.