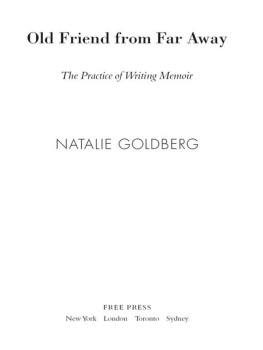

Long Quiet Highway

Waking Up in America

Natalie Goldberg

For my teacher

Dainin Katagiri Roshi

with boundless love, gratitude, and appreciation

Introduction

THERE IS AN ORDER of Buddhist monks in Japan whose practice is running. They are called the marathon monks of Mount Hiei. They begin running at one-thirty A.M. and run from eighteen to twenty-five miles per night, covering several of Mount Hieis most treacherous slopes. Because of the high altitude, Mount Hiei has long cold winters, and part of the mountain is called the Slope of Instant Sobriety; because it is so cold, it penetrates any kind of illusion or intoxication. The monks run all year round. They do not adjust their running schedule to the snow, wind, or ice. They wear white robes when they run, rather than the traditional Buddhist black. White is the color of death: There is always the chance of dying on the way. In fact, when they run they carry with them a sheathed knife and a rope to remind them to take their life by disembowelment or hanging if they fail to complete their route.

After monks complete a thousand-day mountain marathon within seven years, they go on a nine-day fast without food, water, or sleep. At the end of the nine days, they are at the edge of death. Completely emptied, they become extremely sensitive. They can hear ashes fall from the incense sticks and they can smell food prepared miles away. Their sight is vivid and clear, and after the fast they come back into life radiant with a vision of ultimate existence.

I read about these monks in a book entitled The Marathon Monks of Mount Hiei, by John Stevens (Shambhala, 1988). It was just before I went to teach the first of four Sunday afternoon writing seminars at The Loft in Minneapolis. I was excited by what I read and naturally I wanted to share it. I stood behind the podium and carried on to fifty Midwestern writers and would-be writers about how the monks became one with the mountain they ran on, how they knew the exact time each species of bird and insect began to sing, and when the moon rose, the sun set, the wind changed direction.

I was twenty minutes into the seminars two hours, telling about the monks, when I looked up and paused. I guess you want to know what the marathon monks have to do with writing?

Well, they have everything to do with it. The way I see it, you either break through in your writingsay what you really need to sayor head for Mount Hiei. As a matter of fact, take a gun with you next time you go to a caf to write. If you dont connect in your writing that day, just shoot yourself. Vague writing on Mondayoff with the little toe. Tuesday, no betterthe big toe. Get the idea?

Why do the marathon monks go to such extremes? They want to wake up. Thats how thick we human beings are. We are lazy, content in our discontent, sloppy, and asleep. To wake up takes the total effort that a marathon monk can exert. I told my class on the last day of the four-week seminar, Well, you have two choices: Mount Hiei or writing. Which one will you choose? Believe me, if you take on writing, it is as hard as being a marathon monk.

There is a story about Hui-ko, the Second Ancestor of Zen, who found Bodhidharma in a cave where he was meditating for nine years. Bodhidharma was the first patriarch, or ancestor, of Zen in China and, in fact, he brought Zen there from India. Day and night, Hui-ko begged Bodhidharma for the teachings. Please, master, I beseech you. Make my mind peaceful. Bodhidharma ignored him and continued to sit in meditation. This went on for a long time: the beseeching and the ignoring. Then one evening in December, there was a huge blizzard. It snowed all night and all the next day. Hui-ko just stood outside the cave without moving, until the snow was waist high. He was waiting to be recognized by Bodhidharma. Finally, he took out a knife and cut off his left arm. He threw it in front of Bodhidharma. You can imagine the red blood on the white snow. With this, Bodhidharma looked up and asked what he wanted.

There is another Zen story about a beautiful woman who came to a monastery and wanted to practice. The head monk said, If you want to join a monastery, first you must get married and raise three children. Then you can come back. She did this and returned years later. She was still refused entry into the monastery. The head monk said she was too beautiful. She would cause trouble for the other monks. She wanted to practice so badly that she went home and scarred her face. This time when she went to the monastery, they let her in.

Are these stories metaphorical or are they true? I believe they are true. There are people burning to realize the truth of existence and these are the extremes they will go to. Why so violent? Is Zen a violent practice? No, no more so than Jesus Christ being pinned to the cross or Abraham taking his son to be sacrificed.

There is a proliferation of writing books in America. They are very popular. People would rather read about how to become a writer than read the actual products of writing: poems, novels, short stories. Americans see writing as a way to break through their own inertia and become awake, to connect with their deepest selves.

Yes, writing can do this for us, but becoming awake is not easy. One must be persistent under all circumstances and it is not always exciting. It is hard. It is a long quiet highway.

Recently, I drove alone from Minneapolis to New Mexico in late December, the darkest time of the year. I had to cross the southern border of Minnesota, drive straight through Iowa, across Kansas, into Oklahoma and Texas. I had to drive through an hour of sleet near Des Moines, past empty fields and funky cafs that said Elvis ate here. I had a great moment listening to Jessye Norman blast out spirituals in her operatic voice on my car stereo, just as I turned a corner on a thin highway in Kansas. The half moon and one evening star were directly in front of me. A train roared by on my right. The moment was over and I was tired, pulling into a Best Western at ten P.M. in the town of Liberty on the Oklahoma border. What I wanted was to love all of this: my weariness, the wind lifting as I got out of the car at the Texaco station.

To love is to wake up. How do we wake up without becoming a marathon monk on Mount Hiei? Well, some of us will have to go to Mount Hiei. There is no other way. The rest of us must work as tellers in banks, drive our children to school, wash the kitchen floor, buy groceries. The marathon monks go all the way to the edge of death, so they may come back and be alive, so they can know gratitude for this moment. We need to wake up when we buy groceries, push the cart down the aisle, see labels, count out change, feel our step on the floor tile. Every moment is enormous, and it is all we have.

About twelve years ago, Chris Pirsig, the son of Robert Pirsig, who wrote Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, was senselessly murdered near the San Francisco Zen Center. The killers knifed Chris and ran. They did not take a wallet (I dont even know if Chris had one on him). I was sitting a seven-day meditation retreat in Minnesota. It was December. We all knew Chris. Rumors spread quickly during breaks, even though we were supposed to remain silent. We all awaited our teachers talk that morning. Katagiri Roshi was close to Chris. He would make it all better.

Roshi walked into the meditation hall, bowed, lit incense, sat down. We chanted. Then he spoke: Human beings have an idea they are very fond of: that we die in old age. This is just an idea. We dont know when our death will come. Chris Pirsigs death has come now. It is a great teaching in impermanence.

Next page