Contents

Guide

To everyone who has been told, No, your idea isnt worth a book.

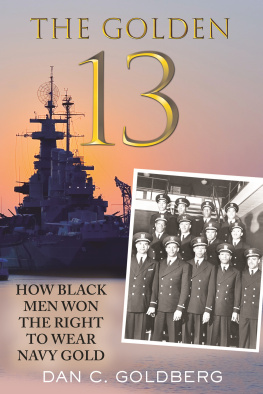

CHAPTER 1

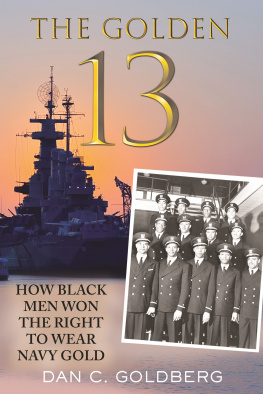

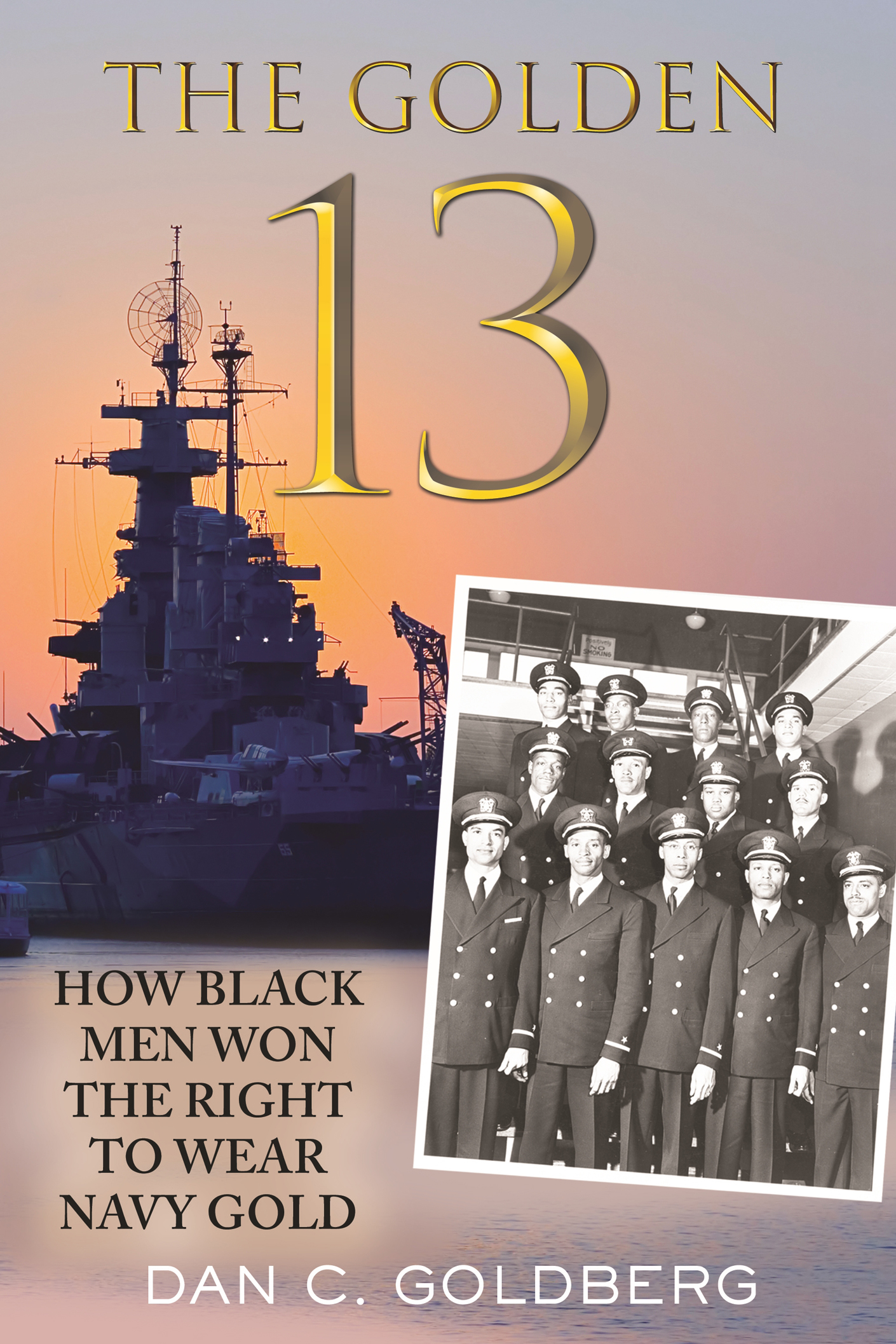

WERE SENDING YOU UP TO GREAT LAKES.

Jesse Arbor, a cheeky and irreverent twenty-eight-year-old, was sweeping for mines off the coast of New England and helping direct ships to their berths in the fall of 1943 when he learned hed been selected to serve aboard the USS Mason.

The Mason, an Evarts-class destroyer escort, was going to be the first warship in US history to boast a black crew. He would finally see real action on the open sea, not just operate off the coast.

My chest flew wide open because I was so proud, Arbor recalled.

Arbor was just a tad over six feet tall, with broad shoulders and powerful thighs that gave the two-hundred-pound football stud surprising agility. He had enlisted in the Navy the year before, only a few months after it was announced that black men could try for a general-service rating, the first time the Navy allowed them to do more than cook, clean, and serve white men aboard ship. Black men could now train as gunners mates, machinists mates, quartermasters, and electricians.

After twelve weeks of boot camp, where Navy customs and regulations were so drilled into his consciousness that they became second nature, Arbor had spent sixteen weeks at quartermaster school. He studied navigation, flashing-light communications, sextants, compasses, steering, and other nautical skills at Great Lakes Naval Training Station, in Great Lakes, Illinois, close to where his parents lived, in Chicago.

He was a middling student at Great Lakes, graduating in April 1943 as a quartermaster third class, the lowest rating for new navigation experts. His first assignment was at a receiving station in Boston, where he spent August and September aboard the USS Bulwark, an Accentor-class coastal minesweeper, a relatively small ship designed for protecting harbors and bays. The crew left between five-thirty and six every morning and spent eight hours sweeping for mines in the cold, choppy waters off New England.

This could be dull work, but it was still considered a plum gig for a black man at the time. Many black sailors with the same training spent their days waxing floors in the barracks, washing pants, and cleaning toilets, a reminder of the racism that governed social relations in twentieth-century America as it fought for democracy abroad. Though black men had been training for the general-service ratings for more than a year, the Navy had thus far limited their assignments to shore establishments or guarding the coast.

But the Mason was no minesweeper. This was a warship that would patrol the Atlantic, fending off German U-boats.

This was where the action was.

By the end of 1942, U-boats had sunk nearly 1,200 US merchant vessels attempting to supply Great Britain with military equipment, food, and fuel. The supply lines were key to winning the war, and the Navy developed destroyer escorts such as the Mason to combat German submarines. The destroyers carried depth charges and antisubmarine weapons known as hedgehogs. They had mounted three-inch, fifty-caliber guns, as well as anti-aircraft guns. They had sophisticated tracking equipment that used high-frequency radio, radar, and sonar.

No black man had ever worked as a quartermaster on a ship like this.

The height of Arbors ambition was to be a quartermaster aboard the Mason, where he could play an active role in defending his country. Maybe, one day, he could even earn a promotion to chief quartermaster. That he would help break a color barrier by serving on the first warship with a black crew only added to his excitement.

Arbors bags were already packed when orders suddenly changed. He was told that he would not be going aboard the Mason. He wasnt told why.

He could barely contain his rage, and the news that he had been given leave for Christmas did little to assuage his disappointment.

When Arbor returned to Boston from a trip home to Chicago, the first thing he did was wash his clothes. To pass the time, he started playing poker with some of his Navy buddies. Sitting in his skivvies, Arbor heard someone say that he needed to report to the officer of the deck. Annoyed, he didnt even look up.

Hell, I just left there, he said.

No answer.

When Arbor finally raised his head, he realized he was addressing a commander.

He stood at attention.

Sir, I dont have anything to put on. In a few minutes, it will all be out of the washing machine, and then Ive got to dry something.

The officer turned and left.

Arbor sat down, but before the next hand was dealt, another officer appeared.

Jesse Arbor, youre wanted by the officer of the deck on the double. Arbor realized no one was interested in his laundry. He borrowed a uniform and rushed out. On the steps, he was met by a captain who handed him a sealed brown envelope.

You have ten minutes to get your seabag lashed up, he said. Theres a car sitting down below to take you to Back Bay Station. In thirty-five minutes, youre going back to Chicago.

That wasnt enough time to pack so Arbor didnt bother. He grabbed, borrowed, and stole what he couldbell-bottom trousers, an undress blue jumper, and a peacoat that didnt quite fit.

His mind was racing. Why was he being sent back to Chicago? Was he in trouble? He remembered that he had once been in a car accident on the corner of Fifty-First and South Park. He had been driving an old Pontiac and he wrecked a doctors Packard. Maybe he was being sent back to answer for that.

When Arbor arrived at Chicagos Union Station, a Beaux Arts masterpiece near the Loop, a sailor greeted him and the two drove thirty-five miles north, to Great Lakes, the headquarters of the Ninth Naval District. Arbor was shown to a barracks, where a couple other black men were waiting.

John Reagan also had hopes that he would finally see some action. He had been in the Navy for eighteen months, an electricians mate of some repute who had impressed his superiors at Hampton Institute in Virginia, home to a segregated training station led by Lieutenant Commander Edwin Hall Downes.

Reagan had spent 1943 aboard the USS Firefly, an auxiliary minesweeper stationed out of Naval Base Point Loma, California. At the end of the year, he was ordered to Norfolk Naval Operating Base, in Virginia, so he could be an electrician aboard the Mason.

Back in Virginia and brimming with excitement, Reagan ran into his old boss, Downes, who by then had been promoted to commander. Downes asked Reagan what he was doing back in Virginia. Reagan stuck out his chest and declared, Im going aboard this DE [destroyer escort] as an AC electricians mate. Im going to get a ship at last.

The hell you are, Downes replied. Come over here to the personnel office and get your orders changed. You come over to my quarters at the school this afternoon or this evening, and Ill tell you a little bit about whats going on.

Reagan followed up with Downes, but the commander was coy.

Were sending you up to Great Lakes for a special class and its something that youll like. Youll be glad youre going. It might lead to something you never suspected.