Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

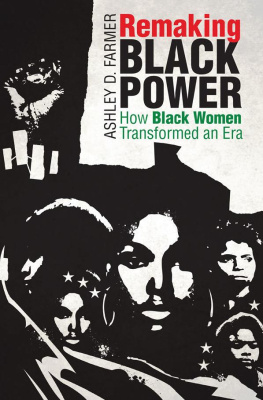

Remaking Black Power

JUSTICE, POWER, AND POLITICS

Coeditors

Heather Ann Thompson

Rhonda Y. Williams

Editorial Advisory Board

Peniel E. Joseph

Matthew D. Lassiter

Daryl Maeda

Barbara Ransby

Vicki L. Ruiz

Marc Stein

The Justice, Power, and Politics series publishes new works in history that explore the myriad struggles for justice, battles for power, and shifts in politics that have shaped the United States over time. Through the lenses of justice, power, and politics, the series seeks to broaden scholarly debates about Americas past as well as to inform public discussions about its future. More information on the series, including a complete list of books published, is available at http://justicepowerandpolitics.com/.

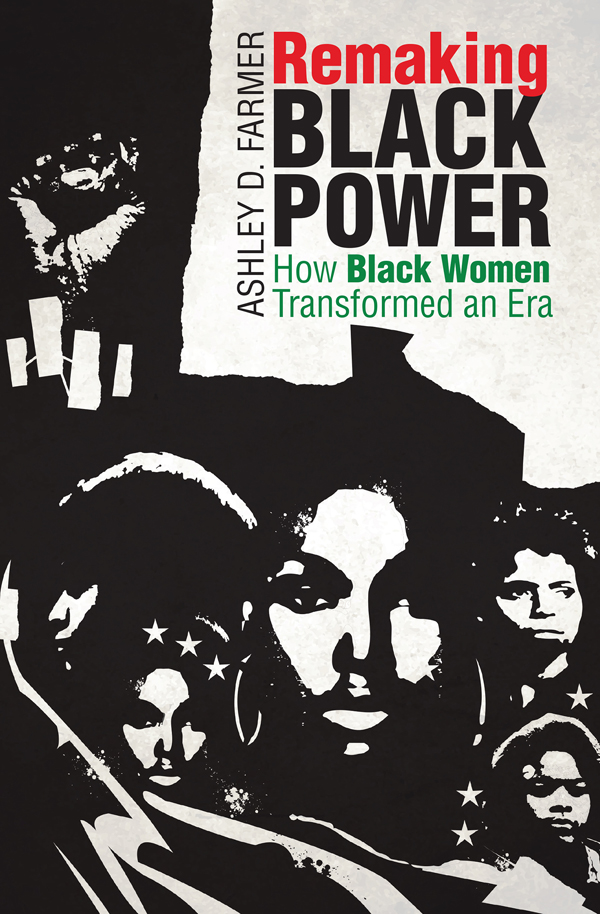

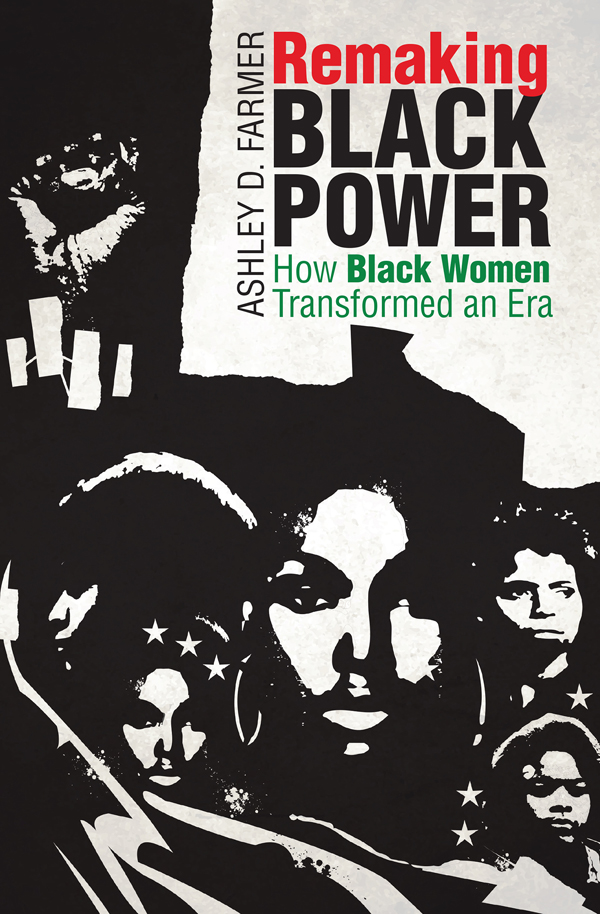

Remaking Black Power

How Black Women Transformed an Era

Ashley D. Farmer

The University of North Carolina Press CHAPEL HILL

This book was published with the assistance of the Authors Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2017 Ashley D. Farmer

All rights reserved

Set in Espinosa Nova by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Farmer, Ashley D., author.

Title: Remaking black power : how black women transformed an era / Ashley D. Farmer.

Other titles: Justice, power, and politics.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2017] | Series: Justice, power, and politics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015698 | ISBN 9781469634371 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469634388 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Women, BlackUnited StatesHistory20th century. | African American womenUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Black PowerUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HQ 1161 . F 37 2017 | DDC 305.48/896073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015698

Cover illustration by Marcus Kiser.

Portions of chapter 3 were previously published as Renegotiating the African Woman: Womens Cultural Nationalist Theorizing in the Us Organization and the Congress of African People, 19651975, Black Diaspora Review 4:1 (Winter 2014): 76112.

For my mother, Madeline Farmer, who instilled in me the love of black womens history;

For my niece, Madeline Wright, who embodies the fearless spirit of the women in this book;

And for Madelines in my family yet to come, with the hope that they can build on the freedom dreams that the women in this book inspire

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

This book, like all things in life, would have not been possible without a village of professionals, professors, friends, and family who have helped me along the way. Ill never be able to fully express how thankful I am to each and every one of them. However, I hope that what follows conveys how grateful I am for each of the communities that helped me reach this point.

The most exciting, humbling, and challenging aspect of this project has been getting to know the lives and thoughts of the women in this book. I want to express my sincere gratitude to the numerous activists who were willing to reflect with me in interviews, invite me into their homes, and chat with me over coffee. These organizers generously shared their memories, personal papers, and possessions with me, broadening my understanding of the meaning of power and the possibilities of black empowerment. Those who could not speak to me personally did so through the archive. I will always be grateful for the many black women who wrote fearlessly and publicly in order to ensure that future generations would have a road map to guide us in developing differently constituted futures.

The wonderful intellectual community at and around Harvard University nurtured my nascent ideas about how to capture these activists thoughts in ways that honored their contributions to our current understandings of race, gender, and empowerment. I owe a debt of gratitude to Nancy Cott, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Peniel Joseph, and Tommie Shelby, who were vital intellectual mentors and thought shapers and without whom this project could not have developed. They set the scholarly bar high, provided a model for rigorous scholarship, and always pushed me to produce my best work. My community at Harvard also extended to people like Linda Chavers, who supported me personally, listened during the bad days, and provided insight and advice on the worst days. Most importantly, on the days I insisted that I was going to quit, she never let me (seriously) consider it. Peter Geller has listened, with patience, to my many ridiculous ideasacademic and otherwiseand offered great advice and a good laugh. I have no doubt that this process would have been far more difficult without him. I would also like to thank Laura Murphy and Amber Moulton. These two women have consistently been a sounding board and offered advice and insight that has helped me navigate the academic maze. I am extremely grateful for their wise words about both academia and life.

This project continued to take shape within a vibrant community in the African and African Diaspora Studies Department at the University of Texas at Austin. In addition to providing funding so that I could complete the first stages of this project, the department offered a welcoming community in which to work. I owe a great deal of gratitude to those scholars who were there during my tenure: Daina Ramey Berry, Tshepo Chery, Tiffany Gill, Kali Nicole Gross, Frank Guridy, Minkah Makalani, Stephen Marshall, Eric Tang, Lisa Thompson, and Shirley Thompson. This community welcomed me and nurtured me in more ways than I can express, and I appreciate their support more than they know.

Friends and colleges at the Clayman Institute for Gender Research were also great writing partners, readers, and friends as the project continued to develop. The institute provided funding and a work space in which I was able to complete book revisions. It also cultivated an intellectual community that fostered my scholarly and professional growth. I am especially grateful for the company and support of Alison Dahl Crossley, who was and remains a wonderful friend, and who has constantly encouraged me to push through the hardest parts of completing and publishing this book.

Duke University not only offered funding and a space within which to work but also provided me with a wonderful scholarly community. Whether it was in the History Department colloquia or through funding from the Deans Office, Office of the Provost, and the Womens Studies Department to workshop the book in its earlier stages, this project benefited from a gracious community that offered critical insights into its subject matter and form. I also benefited from a supportive writing and scholarly community that included Annabel Kim, Eli Meyerhoff, Jecca Namakkal, David Romine, and Gabe Rosenberg. I owe special thanks to Adriane Lentz-Smith for her formal and informal mentorship throughout my years in Durham, Alisha Hines for her generous support, and Monica Huerta for her friendship and endless supply of laughs. Thanks, team!

My scholarly and professional community at Boston University helped me cross the finish line. The funding and time that the History Department and African American Studies Program offered, as well as the generous support from friends, colleagues, and students, all provided a welcoming community within which to work and helped further my thinking on the project in its final stages.