In memory of

James Lee Farmer

In this pleasant soile

His farr more pleasant Garden God ordaind;

Out of the fertil ground he causd to grow

All Trees of noblest kind for sight, smell, taste;

And all amid them stood the Tree of Life,

High eminent, blooming Ambrosial Fruit

Of vegetable Gold

Milton, Paradise Lost , Book IV

By their trees ye shall know them, may be said of

California cities.

San Francisco Call (1904)

A eucalyptus has its implications

where I come from: it means the autumn winds

return each year like brushfires from the desert,

return as dry reminders of the oaks

whose place this was: the valley oak, blue oak,

and the oracle which thrive on little water.

And eucalyptus means the orange groves

once flourished here, that rivers were diverted,

that winter was denied and smoke hung low

over the valley the night of the first frost

smudgepots warming and darkening the sky...

Kevin Hearle,

Each Thing We Know Is Changed

Because We Know It

Contents

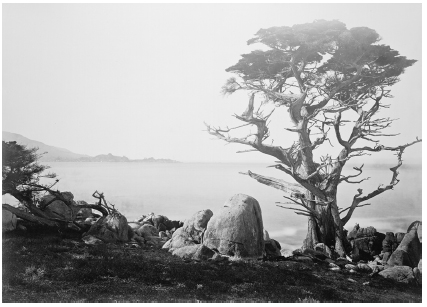

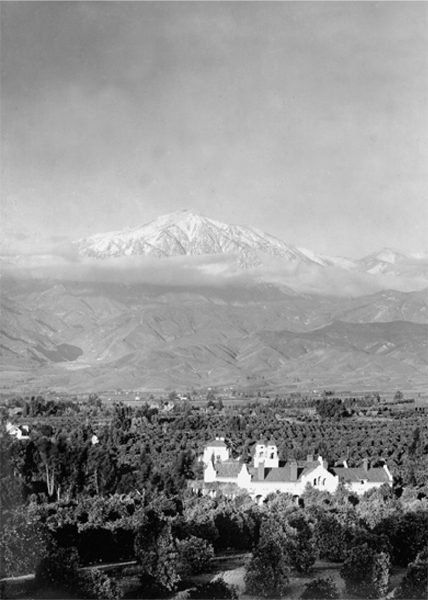

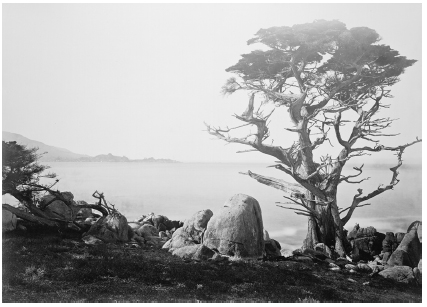

AT CYPRESS POINT ON CARMEL BAY, A PUNCH SHOT AWAY from the fairways and greens of the world-famous Pebble Beach Golf Links, peculiar things grow where surf meets rock. Monterey cypress occurs naturally here and only here. Pruned by salt and bent by wind, the sea-level conifers look positively subalpine. Tourists of an earlier era likened these scenic deformities to pterodactyls, octopuses, gnomes, and wraiths. One travel writer averred that their queer, unreal, fantastic shapes were more startling and uncanny than anything imagined by Dante or Dor.1

The Pacific Improvement Company, the real estate division of the Southern Pacific Railroad, obtained Cypress Pointpart of a former Mexican land grantin 1880. To stimulate tourism, the firm built a scenic road, 17-Mile Drive. As a stagecoach route, then as a one-way paved automobile tollway, the coastal drive wound through the main 50-acre grove with its approximately eight thousand cypresses. Tour operators spun romantic tales about the botanical attractions, and guidebooks repeated their bogus claims: cypresses as old as Christ, organisms identical with the sacred cedars of Lebanon. Standout specimens acquired names such as Witch Tree and Ostrich Tree. Over the years, many of these arboreal contortions suffered structural damage. Through attrition, the status of landmark fell to Lone Cypress, formerly known as a lone cypress or simply a solitary tree. It clung to a rocky promontory. Visible from the midway point of 17-Mile Drive, this improbable life-form attracted painters and photographers from the nearby art colony of Carmel-by-the-Sea. Tourists beat a path to the keep, using the trees exposed roots as steps. The Pacific Improvement Company, fearful that its living property would collapse into the waves, built a retaining wall, attached guy wires, and restricted pedestrian traffic. The next (and current) owner, Pebble Beach Company, increased the vigilance: you cant get closer than 70 yardsnear enough for a zoom-lens snapshot. Multiple tour buses stop here every summer day. Lone Cypress is ostensibly the worlds most photographed tree and one of Californias signature sights. It shows up on postcards, calendars, posters, websites. People praise the photogenic plant as an inspirational symbol of fortitude, strength, tenacity, and rugged individualism.

The singular tree has a parallel life as a corporate emblemLone Cypress, a trademark of quality . Pebble Beach Company, a golf resort, calls it the basis of our brand identity system. The company adopted the tree in 1919 and updated the logo several times over the ensuing decades. The strength of Pebble Beachs trademark was demonstrated in U.S. District Court in 1985, when the company successfully sued a retailer for selling merchandise emblazoned with a stylized cypress and the name Pebble Beach. Although the company did not own the place-name, ruled the judge, it could claim exclusive use of the graphical tree. To protect shoppers from confusion, the judge enjoined competitors from using the companys intangible asset. The trademark applied to the logo, not to the organism. Nevertheless, Pebble Beach sent a few cease-and-desist letters to landscape photographers in 1990 for illegally reproducing its branded plant. After Cypressgate made the national newsand after experts in trademark law lambasted the companyPebble Beach retreated to its fallback position: as property owner, it can oblige visitors to refrain from commercial photography; its guests implicitly agree to this contract when they pay the admission fee to the scenic drive. The business still alleges that its trademark covers the tree.2

The logo may outlive the plant. Lone Cypress is roughly the age of the United States and near the end of its life span. Weakened by past arson attacks and termite invasions, it relies on padded cable supports for stability. Company arborists nurse the tree with supplements of mulch, potash, and phosphorous. Anticipating the inevitable, Pebble Beach has cultivated a future transplant, Lone Cypress Jr., in a secluded spot where onshore breezes will, with luck, train it into a similar wizened appearance.3

The concept naturally occurring hardly applies to Monterey cypress anymore. Carmel Bay may claim the prototypes, but no longer do you have to travel to Monterey County, or even California, to see the species. Once renowned for being restricted, Monterey cypress is now widespread. Australians and New Zealanders propagated vast quantities of these California trees in the late nineteenth century. In the same era, California farmers and landscapers used cypresses, often in combination with Australasian eucalypts, as hedges and windrows. Away from the windy coast, the species assumes tall, erect, symmetrical, pyramidal forms. Since the Depression, the city of San Francisco has annually illuminated an attractive specimen in Golden Gate Park as its official Christmas tree. Curiously, a species reduced to its last stand at Carmel Bay grows with weed-like rapidity in other places.4

To explain the original island-like isolation of the cypress, Californians formerly turned both to scientific and historical speculation and to flights of fancy. Perhaps ocean currents had carried seeds from cedar groves in Japan. Perhaps the trees had been planted by Franciscans who brought scions from Lebanon; or they might have been cultivated by a race of Syrians, now vanished, that migrated to prehistoric California. The most popular conjecture centered on Chinese monks in North America. This horticultural legend accrued some credibility thanks to the lord abbot of the Buddhist Church of Sacramento, the Venerable Right Reverend Dr. Sri Bishop Leodi Ahmed Mazziniananda Swami. The Golden State was a fitting destination for this protean man. Born in Isfahan, Persia, in 1827, Mazziniananda spent his adolescence in Lhasa, Tibet, studying the priesthood under the Dalai Lama. Later he earned university and postgraduate degrees at Oxford, Heidelberg, Paris, and London, where he became friends with Arthur Conan Doyle. Mazziniananda came to the United States in 1893 and commenced spreading the Dharma, gradually working his way west, arriving in California a decade later. He remained in the land of sunshine until his death in 1931. As a lively octogenarian, Mazziniananda headed the Buddhist Educational Bureau at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, where he gave a public lecture that included his etiology of the Monterey cypress.5

Next page

![California Coastal Commission - California Coastal Access Guide [Lingua Inglese]](/uploads/posts/book/157220/thumbs/california-coastal-commission-california-coastal.jpg)