CONTENTS

To my grandchildren

ILLUSTRATIONS AND FIGURES

Original drawings by Dawn Burford

PREFACE

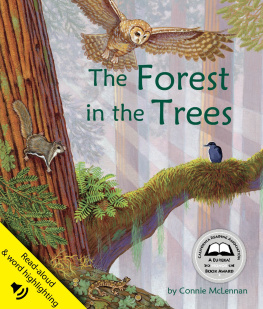

AT BOSCOBEL IN Shropshire in the English Midlands stands the Royal Oak, where the provisional King Charles II is alleged to have hidden from Cromwells men after the Battle of Worcester, which ended his premature attempt to restore the monarchy. Why not? All this happened only about three and a half centuries ago (1651) and oaks may live for two or three times as long as that. Robin Hood and his Merry Men are said to have feasted beneath the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshireand so they might have, for if they existed at all it was in the time of Richard I, in the late twelfth century, and the Major Oak was alive and well at that time. A yew I met in a churchyard in Scotland has a label suggesting that the young Pontius Pilate may once have sat in its shade and wondered what the future held. Its an audacious claim. But the tree was there, even if Pilate wasntalready some centuries old at the time of Christ.

Theres a kauri tree in New Zealand called Tane Mahuta (the oldest and biggest kauris are given personal names), with a trunk like a lighthouse, that was four hundred years old when the Maoris first arrived from Polynesia. For the first nine hundred or so years of Tane Mahutas life, the moas, related to ostriches but some of them half again as tall, would have strutted their stuff around its buttressed base, threatened only by the commensurately huge but short-winged eagles that threaded their way through the canopy to prey upon them. Now the moas and their attendant eagles are long gone but Tane Mahuta lives on. Many a redwood still standing tall in California was ancient by the time Columbus first made Europe aware that the Americas existed. Yet the redwoods are striplings compared to some of Californias pines, which germinated at about the time that human beings invented writing and so are as old as all of written history. These trees out on their parched hills were already impressively old when Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt, or indeed when Abraham was born. So it is that some living trees have seen the rise and fall of entire civilizations.

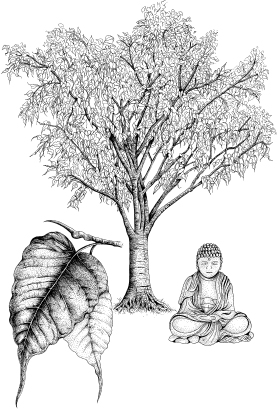

Trees inspire: the Buddha received enlightenment under a peepul tree.

Some redwoods, Douglas firs, and eucalypts are as tall as a perfectly respectable skyscraper, and theres an extraordinary banyan in Calcutta that would cover a football field. Many are host to so many other creatures that each is a city: as cosmopolitan as Delhi or New York and far more populous than either. Creatures of all kinds may feed on trees, or maraud among their branches. At least, I know of no arboreal octopusesbut there could be, out in the mangroves. Theres many a tree-happy crab in the mangroves, as I have seen for myself, and the robbers of the Pacific islands, giant hermit crabs, come on land (as many crabs do) to feed on coconuts. When the Amazon is in flooddeep enough to submerge well-grown trees entirely, over an area not far short of Englandthe fish feed on fruit and river dolphins race through the upper branches of what should be the canopy, while monkeys hop and swim from crown to crown like ducks. In New Zealand little blue penguins nest in the forest at night with ground parrots (or at least they do on the sanctuary of Maud Island). In the 1970s, in the crown of one fairly modest tree in Panama a scientist from the Smithsonian Institution counted eleven hundred different species of beetleyet he didnt bother with the weevils, although they are beetles too, or look closely at the host of creatures that are not beetles, or those that were living in the roots. I once found myself in an old kapok tree in Costa Rica in which biologists had thus far listed more than four thousand different species of creatures.

Yet a tree cannot afford simply to serve as someone elses monument and feeding ground. From the moment the seed falls on to the forest floor (or the sand of the savannah, or a fissure in some mountain crag, or a glaciers edge, or a lakeside, or a tropical seashore) to the moment of its final demise, perhaps a thousand years later, the tree must compete through every secondfor water, nutrients, light, and space; and to fend off cold, heat, drought, flood, toxicity, and the host of parasites and predators of all conceivable kinds (from a trees point of view, squirrels or giraffes are predators). A village or a civilization may choose to make a tree their symbol. The entire nation of Brazil is named after a treefor brazilwood was known to Europeans before the country was. But however we may choose to ennoble it, the tree must fight its corner, a creature like all the rest. If it did not fight it would be dead. Even when it sheds its leaves to ride out frost or drought, its cells are still busy beneath its armored bark. Were it not so, the leaves could not burst out as they so spectacularly do when the temperate spring or the tropical rains returnor sometimes in advance of the rains, to the delight of camels and goats, which thus may find green fodder in the depths of drought. In many trees, too, tropical and temperate, the flowers emerge before the leaves, which keeps the path clear for pollinating winds, bees, or bats. Since there are no leaves to provide nourishment, the flowers must be fed from the trees reserves in its trunk and roots. The living timber is multipurpose: a prop, a conduit, a larder.

Flowers, of course (and the cones of conifers), meet lifes other demand: not simply to survive and grow but to reproduce. Here, the trees immobility is a particular drawback. Many trees reproduce without sex, commonly though not exclusively by root suckers, but all trees (to my knowledge) practice sex as well. For sex, gamete must meet gamete: sperm and egg in the case of animals and primitive plants, pollen and ovule in the case of conifers and flowering plants. Since many flowers of many trees are hermaphroditic (male stamens and female carpels on the same flower), and many trees (like oaks and many conifers) are monoecious (the individual flowers are exclusively male or female, but both kinds occur on the same tree), it may seem easy enough for trees to pollinate themselves. But on the whole they dont. One of the botanical surprises of recent decades (finally proven by genetic studies) is the length to which most trees go to avoid self-fertilization. Outcrossing is the norm: pollination of, and by, other individuals who, of course, are of the same species but preferably are not too similar genetically. To achieve outcrossing, trees must elicit the help of the windor bribe or otherwise coerce a variety of animals, from flies and beetles and bees to birds and batsto carry their pollen for them. Some temperate trees (like apples and horse chestnuts) are pollinated by animals, though most (like oaks and birches and beeches) are content to use the wind. But in tropical forests, where most kinds of trees live, animal pollination is the norm; and because life is competitive, the mechanisms that have evolved for this have become more and more elaborate. Thus for every one of the 750 different fig species there is a corresponding specialist wasp species to pollinate it; and each wasp knows its own fig (although, as recent studies have shown, the relationship between figs and their wasps is not quite so cozy as had been supposed). When the ovules are fertilized and become seeds, encased in fruits (or some other kind of fruiting body) they must then be dispersedsometimes again by wind but often by another, entirely separate, suite of animal accomplicesbirds and fruit bats and rodents and orangutans, whose help must again be actively co-opted.

Next page