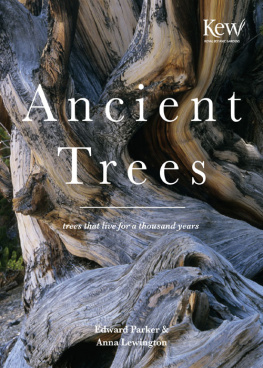

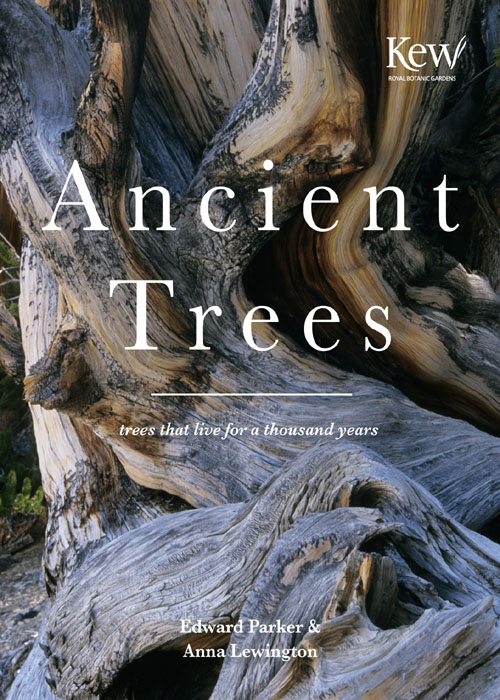

First published in the United Kingdom in 2012 by

Batsford, 10 Southcombe Street, London W14 0RA

An imprint of Anova Books Company Ltd

Copyright Batsford 2012

Text copyright Edward Parker and Anna Lewington 2012

The moral right of Anna Lewington and Edward Parker to be identied as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

First ebook publication 2012

Ebook ISBN: 9781849940580

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available in Hardback

Hardback ISBN: 9781849940580

Foreword

I am fortunate in having a wonderful job as the head of the arboretum at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and to have travelled extensively across the globe with my work, observing and collecting seeds and herbarium specimens of trees to maintain and improve the scientific value of the temperate woody plant collections in the arboretum.

One of my first seed-collecting expeditions was in 1985, to the temperate regions of Chile, where there are some incredible forests and amazing trees, including some very rare ones that in cultivation can only be found in specialist collections. It was here that I saw my first exceptionally large ancient trees of around 2,000 years old in their native habitat, the Cordillera de Nahuelbuta in the Araucana region of Chile. These trees were monkey puzzles (Araucaria araucana). As we rounded the bend of a dirt track on our way to the mountains, we came upon a breathtaking sight: the distant horizon, with the architectural silhouettes of this uniquely shaped tree dominating the skyline, gave me a memory that will be with me for the rest of my life. Even though I was familiar with this tree, common in gardens at home, I was nonetheless fascinated by this pure forest of prehistoric-looking living fossils, and I needed to know and understand more about the natural history and ecology of this incredible relic.

We spent several days botanizing and collecting, among some of the largest monkey puzzles that I have ever seen and am ever likely to see again, their bases resembling giant elephants feet and their distinctive, dark-barked trunks rising up into the foggy skies, where their branched tops dominate. Later into the six-week expedition we ventured further south in Chile to see the alerces (Fitzroya cupressoides) of Alerce Andino National Park in the Los Lagos region of the Andes. Like the monkey puzzle, this is a very rare tree in the wild, threatened with over-exploitation because its highly durable timber is in demand for roof shingles, and to see any specimens of this tree would be a treat. On seeing these magnificent 3,000-year-old monoliths of the Chilean forests, I was even more bewildered and lost for words. They are huge trees, growing to heights of 60m (197ft), with incredibly large boles in comparison with the smaller, cultivated specimens I had seen growing in gardens on the west coast of Scotland, where the climate from the Gulf Stream provides good conditions for growth. While we photographed and studied one extremely large tree, there was an eerie silence except for the roar of the river and a few birds, and every time I pass the 4m (13ft) tall specimen by the Redwood Grove at Kew, I am immediately reminded of this moment and transported back to the forest in Chile, clearly picturing these denizens of the forests of Alerce Andino and longing to return one day to catch up with them.

From those two pivotal moments on I became more intrigued by old, historic trees and the stories they hold, increasing my passion for working with trees even further. I love to hear other peoples tales of meeting ancient trees, and wherever I am fortunate enough to go botanizing or collecting, I always ask local people if they know of any old or large trees, and relish the opportunity to observe them.

In 2001, while I was travelling in Sichuan, China, our guides, knowing my interest in old trees, took a detour into a village nestling on the banks of the Dadu River called Lengji to see an old maidenhair (Ginkgo biloba) tree. As we pulled off the road, the sheer size of this tree was evident, towering above the houses in the village. As we worked our way through the tiny network of paths, we finally reached our target. You can never prepare yourself for what you are about to see, and these first sightings all provide the same exhilarating feeling. The size, the girth and the spread all filled me with awe, but in addition, this tree had a beautiful red temple constructed in its base, complete with incense and candles. This very tree was seen and photographed by our most noted plant collector, Ernest Wilson, in 1908. The entire town came out to see us and were so excited that we had come all the way from England to see their tree that they gave us seeds, which now reside as trees in the arboretum at Kew, a living memory of the Lengji Ginkgo.

I remember my first visit to see the giant redwoods (Sequoiadendron giganteum) in Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park, in great detail I had read so much about these revered giants and seen pictures, but nothing could have prepared me for that day. When I first saw Grizzly Giant, the largest tree in the park with a diameter of 8.23m (27ft) at its base and over 2,500 years old, it was awe-inspiring: it is an amazing tree, holding itself magnificently far above the surrounding canopy and all the other conifers. This was another special moment in my life, and again I will never be able to describe how I felt; a time to contemplate. That very experience now draws me whenever I can to the west coast of the USA and Canada to witness the giants of the Pacific North-west coast: the coastal redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens), the Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and the sitka spruces (Picea sitchensis).

There is nothing more rewarding and inspiring than seeing these trees residing in their natural habitat, characterful trees that carry so many personal memories or have so many meanings and ethno-botanical links to mankind. It is not always possible for everyone to travel to these remote locations and see them in real life, but we are very lucky that the co-author of this book, Edward Parker, has captured so many of these hugely photogenic, ancient specimens in his photographs, and given everyone the opportunity to meet them. When I need some inspiration and Im unable to sit under a monkey puzzle in the Araucana region of Chile, I will sit in the comfort of my home, leafing my way through this wonderful book and being taken back in memory to see some of the ancient trees of the world.

Tony Kirkham

Head of the Arboretum, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

INTRODUCTION

T he research for this book has taken us on a journey of discovery, not just around the world, but also through time. We have encountered giants whose enormous fluted trunks rise up like great cathedrals, and we have stood in groves of gnarled and wizened trees that were alive before the great pyramids of Ancient Egypt were built, standing in a desolate landscape that has remained virtually unchanged for 20,000 years. We have sensed the quiet power of some of the worlds largest and oldest living organisms, and begun to understand the awe and reverence that many peoples in the past have felt. Standing in the presence of some of the worlds oldest statesmen, it was impossible not to feel moved and to reflect upon the transience of our own human lives; impossible not to feel that we are part of natural cycles that are just too large for us to comprehend.