Contents

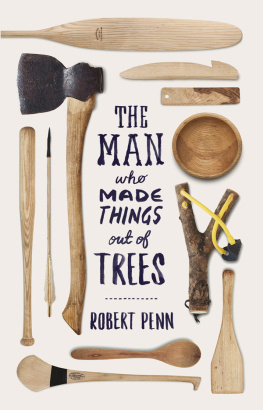

Robert Penn

THE MAN WHO MADE THINGS OUT OF TREES

PARTICULAR BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Particular Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2015

Copyright Robert Penn, 2015

Cover design: Richard Green

Cover photography: Elisabeth Scheder-Bieschin

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-141-97752-2

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

PROLOGUE

Venus of the Woods

the Ash for nothing ill

Edmund Spenser,

The Faerie Queene, Book I

I grew up under an ash tree. It stood over the gate that led from my childhood garden to the fields where my brother and I played out our fantasies. To dash past the elegant, slim-hipped, sweeping form of that ash in winter and to flash beneath its airy canopy in summer was to be transformed into a colonel or a king, a knight or a wizard. That ash was, for many years, the gatekeeper to my dreams.

I cant remember as a child ever making the connection between that tree and many of the things I loved. I dont think I even knew that my prized Dunlop tennis racket, my hockey stick, my cricket stumps and bails, the rocking chair in my brothers bedroom and our toboggan were all made out of ash wood. Yet that tree somehow stuck with me. Ever since then, I have instinctively looked for ash trees in the woodlands and fields, and even in the urban landscapes where I have lived. The presence of the tree was somehow braided into the long journeys I have made around the world. It may even be that this tree was a cardinal point, a lodestar that brought me, at the end of my journeying, to live with my family in a house within a small woodland on the edge of the Black Mountains, South Wales in a landscape similar to that which I knew as a child, a place where ash grows abundantly.

The woodland is on a south-facing slope. Fields and moorland enclose it on two sides. The Arw stream marks the southern boundary. Mixed deciduous trees, including rarely planted species, are arranged haphazardly. Perhaps trees have stood here for a very long time, but it would be wrong to look at this woodland as something eternal and unchangeable. A woodland only represents the natural order of things at a particular moment in time.

When we moved to our house over a decade ago, no one had raised an axe or swung a billhook here since the Second World War, when much of the woodland in the area was felled to provide timber for the war effort. It was a dark, tangled thicket with a canopy of leaves as carefully stitched as a Welsh quilt. The light was thin. The air was restricted. The woodland was somehow lifeless.

I was unsure about what to do with my wood. Then I reread A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold, the early American environmentalist. He wrote: I have read many definitions of what is a conservationist, and written not a few myself, but I suspect that the best one is written not with a pen but with an axe. And, tentatively, one winter I started to coppice the ancient woodland management practice of cutting trees back to ground level to stimulate regrowth. I felled the old, bulging hazel stools along the field boundaries. I thinned out the weakest trees, rendering new vigour to what was left. I created glades. I planted oak trees. I left standing dead timber and rotting wood on the ground. Birds began to nest in the piles of brash. Wildflowers a few wood anemones, celandines, stitchwort, yellow archangel, lords and ladies, woodland violets, foxgloves and bluebells sprung to life.

As I cleared the smaller trees or underwood, the taller trees the single-stemmed, timber trees called maidens began to emerge. The skeletal character of individual trees was revealed: the muscularity of the oaks; the stanchion-like alders along the stream; the silver birch with their flamboyant mops of claret-coloured twigs. Most conspicuous of all in the dormant wood were the ash trees: cast in tender light and naked of leaf, they were grey-green barked, sparsely branched, tall, slender and austere with twigs that rose and fell and rose again at their tips to end in the distinctive witches claws, which scratched against the pearl-grey sky. Ash wears the winter with a grace that no other tree species can match, hence its nickname Venus of the Woods.

The ash or genus Fraxinus, one of twenty-four genera in the Oleaceae family, includes some forty-three species, according to Dr Gabriel Hemery, author of The New Sylva, and they grow within the temperate and subtropical regions of the northern hemisphere. Three species of ash are native to Europe. Of these, European or common ash (Fraxinus excelsior) is by far the most widely distributed and important. Common ash grows from the Atlantic coast of Ireland across Europe to the city of Kazan, five hundred miles east of Moscow. The northernmost limit of its distribution is the Trondheim fjord in Norway at 64 N. The eastern boundary traces the river Volga to Crimea and the Caucasus. The southern edge of common ashs domain starts around 37 N in Iran and takes a rough line through Dalmatia, Italy and southern France, to the Pyrenees. On the Iberian Peninsula, common ash only grows in the mountains. As a general rule, common ash is a tree of the mountains in southern Europe: further north, it is a tree of the valleys and plains.

In Britain, ash is the third most common broad-leaved tree, after oak and birch. It thrives best on deep, fertile loam over outcrops of carboniferous limestone, ideally on well-drained, northern and eastern slopes where the atmosphere is moist and cool. Ash wont grow on waterlogged sites but it will tolerate a wide range of climatic conditions, provided the soils are suitable. It grows better in mixed woodland than in pure plantations and is frequent in hedgerows. Ash is also tolerant of air pollution, making it a popular tree in urban parks and gardens. Ash can even survive where there is almost no soil: it grows like scrub on bare, limestone rocks in upland parts of Yorkshire and Derbyshire, shooting from chinks in the paving.

Normally vigorous and dense-rooted, ash makes significant demands on easily available nutrients in the soil. While it is exacting in this respect, ash is generous in others. It is aristocratically late to leaf. The feathery canopy of an ash tree in late spring and summer is fragile and airy, casting a gossamer shade, which permits plenty of light on to the woodland floor. This encourages a rich diversity of ground vegetation, commonly including oxlip, wood anemones, meadowsweet, ransoms and the wildflower that grows in sweet-smelling ponds of mauve and has the power of Prozac on the British collective consciousness in spring bluebells.