L IVES of the T REES

ALSO BY DIANA WELLS

100 Flowers and How They Got Their Names

100 Birds and How They Got Their Names

My Therapists Dog: Lessons in Unconditional Love

L IVES of the T REES

AN UNCOMMON HISTORY

DIANA WELLS

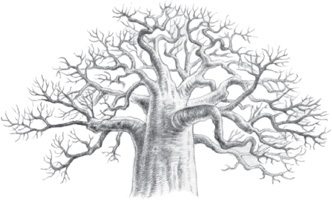

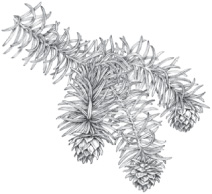

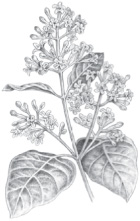

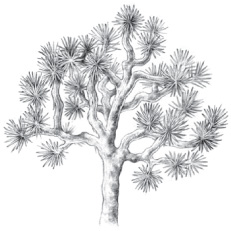

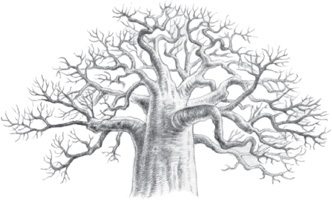

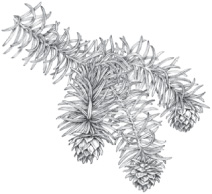

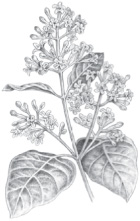

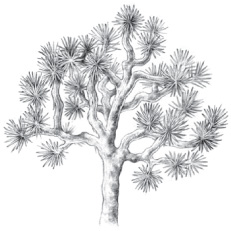

ILLUSTRATED BY HEATHER LOVETT

PUBLISHED BY

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

POST OFFICE BOX 2225

CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA 27515-2225

A DIVISION OF

WORKMAN PUBLISHING

225 VARICK STREET

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10014

2010 BY DIANA WELLS. ILLUSTRATIONS 2010 BY HEATHER LOVETT.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

PUBLISHED SIMULTANEOUSLY IN CANADA

BY THOMAS ALLEN & SON LIMITED.

DESIGN BY ANNE WINSLOW

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

WELLS, DIANA, [DATE]

LIVES OF THE TREES : AN UNCOMMON HISTORY /

DIANA WELLS ; ILLUSTRATED BY HEATHER LOVETT. 1ST ED.

P. CM.

INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX.

ISBN 978-1-56512-491-2

1. TREES FOLKLORE. 2. TREES MYTHOLOGY. 3. TREES HISTORY.

I. LOVETT, HEATHER. II. TITLE.

GR785.W45 2010

398.242 DC 22 2009031669

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FIRST EDITION

In loving memory of my father, Robert Coventry Grieg, and my mother, Betty Burnford Brooke, who loved, and planted, trees.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

O NCE AGAIN I MUST THANK the staff of the Krauskopf Memorial Library, particularly Janet Klaessig and Peter Kupersmith, for nearly a decade of professional assistance, enthusiasm, and friendship. For much-needed help in correcting mistakes, grateful thanks to Inea Bushnaq, Claire Wilson, and Vic Johnstone, who all did far more than should be expected from friends. As always, thanks to my lovely editor, Amy Gash; my publisher, Elisabeth Scharlatt, and my agent, Betsy Amster. Thanks above all, to my family for all they do and all they are.

L IVES of the T REES

INTRODUCTION

T HIS BOOK IS NOT FOR botanists or dendrologists or taxonomists, or even for those want to identify individual trees. It is a book for nonexperts (like me). Our long relationship with trees is a story of friendship. The human race, we are told, emerged in the branches of trees and most of us have depended on them ever since, for food, shade, shelter, and fuel.

Its easy to find examples of humans revering trees. William Cowper marveled in 1786 about the Yardley Oak in an unfinished poem of the same name, calling the tree the king of the woods:

Thou wast a bauble once; a cup and ball,

Which babes might play with ...

............

Time was, when settling on thy leaf a fly

Could shake thee to the root, and time has been

When tempests could not ...

Its equally easy to find examples of humans destroying trees, although felling trees isnt necessarily merciless destruction. Agricultural and horticultural societies need cleared land to grow crops and make gardens. The kind of land on which flowers and vegetables grow best is often where trees also grow best. Even today, with all our technology, we not only need trees to counteract global warming but still rely on their products all the time. We seem to consume as much paper with our computer printouts as we did in our pre-paperless world. Anyone opening this book will be touching what was once a tree and very likely sitting on a wooden chair. Even tree huggers need their goods.

The conflict between use and reverence is not new. Because they are larger and older than we can ever hope to be, because they give shade, wood, food, and shelter, and because they stretch from earth to heaven, trees have been our gods since before recorded time. We know that ancient pagan people worshipped in sacred groves. That was why the Hebrew people were told (in Deuteronomy) that thou shalt not plant thee a grove of any trees near unto the altar of the Lord thy God. In Judges, Gideon is ordered to destroy the altar of Baal and cut down the grove that is by it. In The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1787), Edward Gibbon described pre-Christian Germany where the only temples... were dark and ancient groves, which, so he said, impressed the mind with... a sense of religious horror.

In many cultures certain trees were selected as being especially holy and thought to have souls of their own, or souls of certain gods, or even of dead humans. In Greek mythology humans were quite often changed into trees to save them from a fate that the Victorians called worse than death. The words tree and truth share the original Old English word root, treow. Trees are steadfast, linking the two realities of the dark earth and the bright sky.

The Tree of Life appears in cultures worldwide. Its roots were in the underworld and its branches supported the heavens, thus connecting death to salvation. The branches of the Tree of Life could be perches for the soul; sometimes the souls of children sat on them, waiting to be reborn. In Turkish lore, when a leaf dropped off the Tree of Life, it meant someone had died. The image of perching souls was used in the seventeenth century by Andrew Marvell, in his poem The Garden:

Casting the bodys vest aside

My soul into the boughs does glide;

There like a bird it sits and sings

Then wets and combs its silver wings.

In some cultures to cut down a sacred tree was even punishable by death. And felling a treasured tree was an irreversible way of hurting or insulting an enemy. In the biblical book of Deuteronomy, Gods besieging armies are instructed to cut down the enemys trees if thou knowest that they be not for meat, sparing the fruit and nut trees because the tree of the field is mans life. During the American Revolutionary War, the Liberty Tree in Newport, Rhode Island, was cut down by British troops as a gesture of dominance.

The most important trees in the Christian religion were those that had grown in the Garden of Eden. According to the Bible, every kind of fruit and nut tree was in the garden, as well as the famous Tree of Knowledge, the fruits of which were forbidden. The fruits of the Tree of Life, though, were not prohibited and eating them brought immortality, thus implying that the happiest state for humans would be perpetual life without knowledge. Scholars, especially medieval scholars who worried about such things, could not decide how Adam and Eve could be innocent but also be truly man and wife, joined by God. In what sense were they connubial? One twelfth-century writer, Ernaldus of Bonneval, ingeniously suggested that there might have been