Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memory of my father,

D ONALD F LEMING M AC A RT ,

who always had time for a story

It takes a noble man to plant a seed for a tree that will someday give shade to people he may never meet.

attributed to D AVID E LTON T RUEBLOOD, American theologian and philanthropist

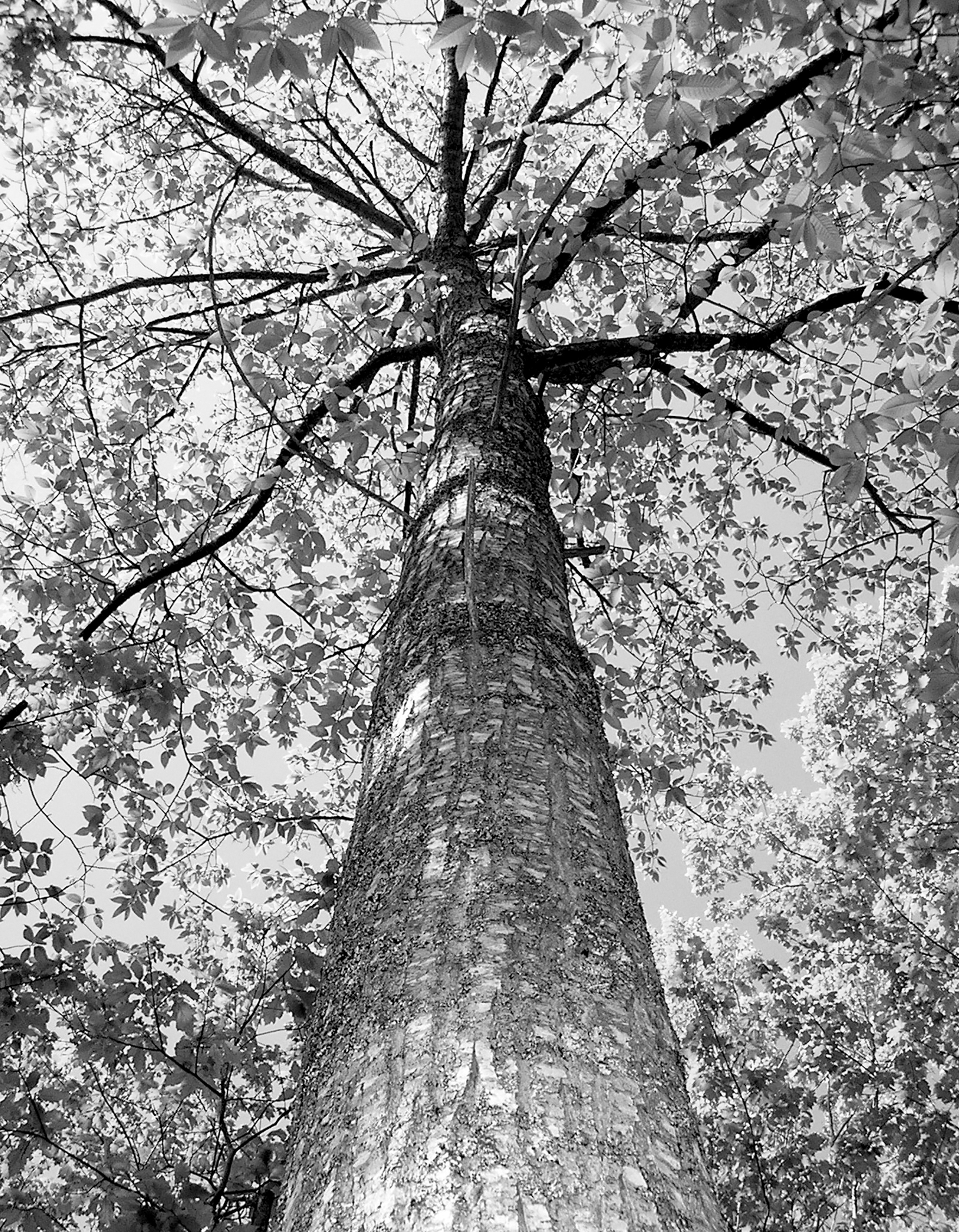

When Hermann Merkel first strolled in the garden of the New York Zoological Park, American chestnut trees grew so tall that they seemed to touch the sky.

H AVE YOU EVER CLIMBED A TREE? Have you ever breathed in the spicy scent of pine trees or looked closely at a leaf?

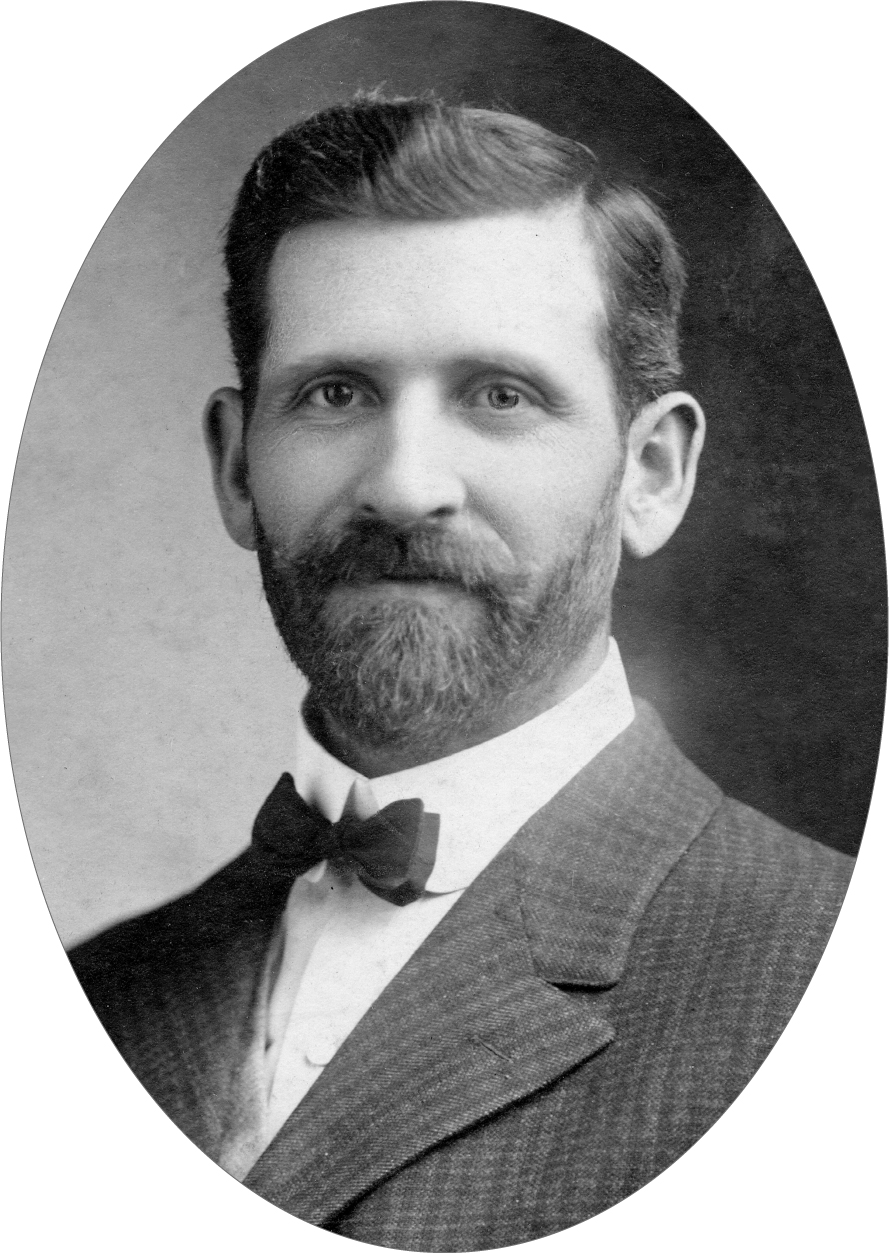

Hermann Merkel was a boy who loved being around trees. He loved them so much that when he grew up, caring for trees became his job. Even before the New York Zoological Park hired Merkel in 1898 to be its chief forester, he could identify every tree in the parkand there were more than a thousand of themby the shape of its leaves and the look of its bark. The trees were as familiar to him as the people in his neighborhood. Merkel spent hundreds of hours walking the parks many paths, doing what he liked to do most: looking at trees. The parks 1,500 American chestnut trees were among his favorites. Some of them had trunks so big that Merkels outstretched arms couldnt completely encircle them. It took twoif not threepeople holding hands to do it. Every year on hot summer days, Merkel cooled off in the shade of these trees. Every year after winter frosts arrived, he ate the trees roasted chestnuts as a sweet, crunchy snack. Every year, that is, until 1904, when disaster struck.

Hermann Merkel was concerned about wounds similar to this one that marred the bark of the parks lovely chestnut trees.

One summer day that year, Merkel found ugly wounds on the trunks of some of his splendid chestnut trees. Their bark had split open and, as with a serious cut in a humans skin, he could see the tissue beneath. When he looked toward the treetops, he saw that the leaves on certain branches had wilted and turned brown. Concerned, Merkel checked other trees: the oaks, the locusts, the birches. All of them looked fine. Only the chestnut trees were hurt. Merkel was unsure what was happening, but it looked like a blight, a disease. He kept a close eye on the chestnut trees and waited to see what would happen next.

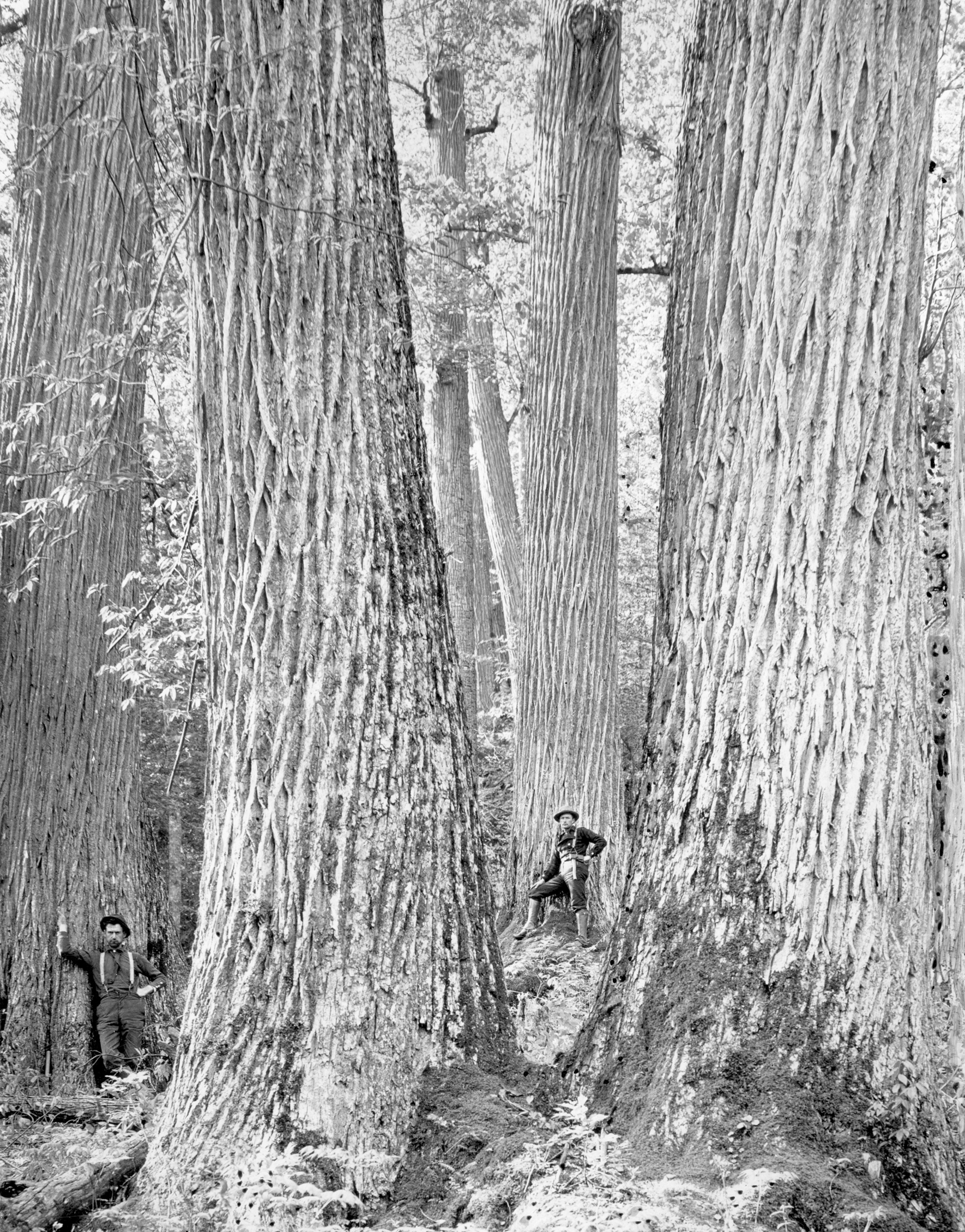

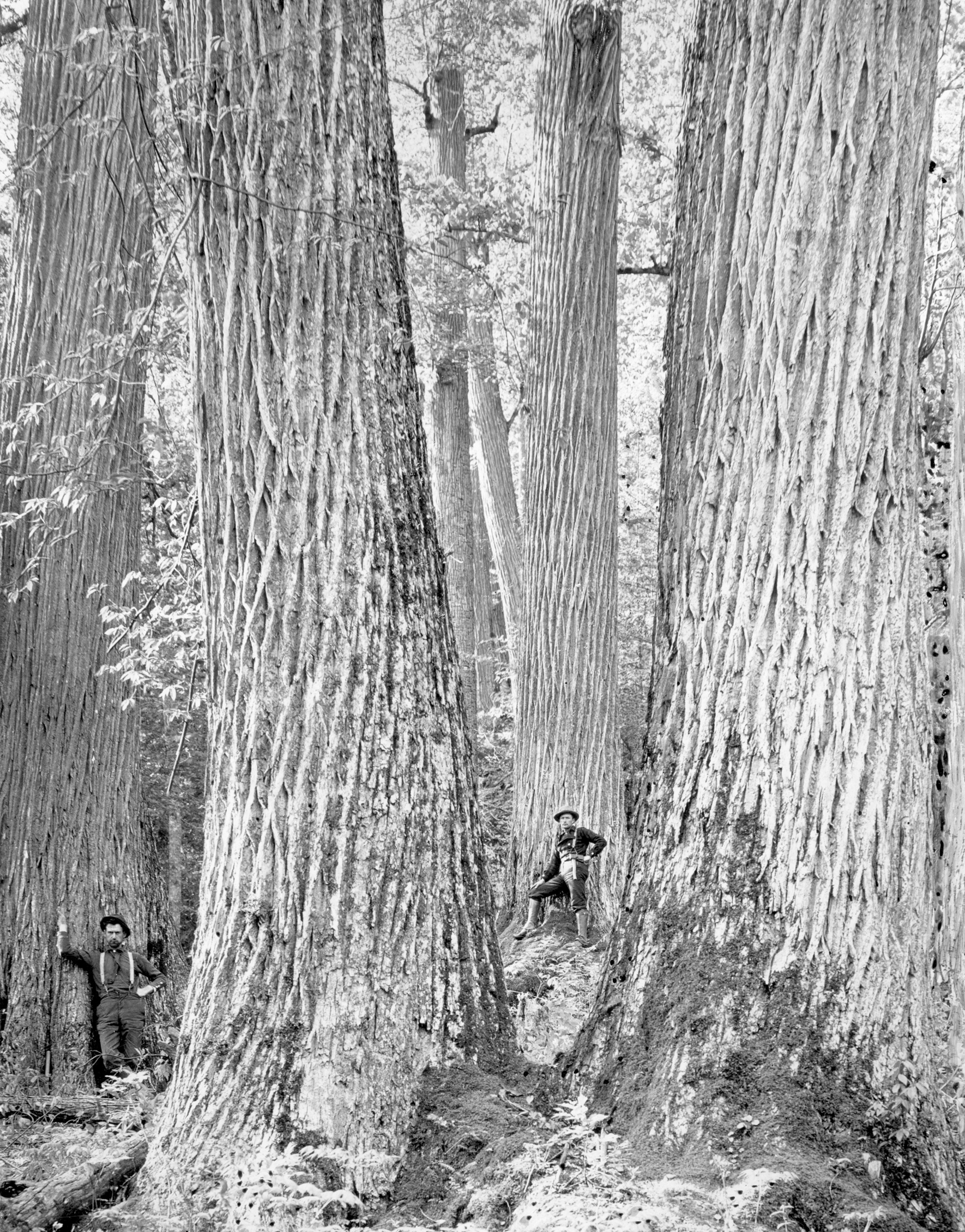

The gargantuan trunks of these American chestnut trees dwarf the men standing beside them.

Working as the zoological gardens chief forester was a job that Hermann Merkel enjoyed.

The situation got worse.

Within days, the injured bark encircled the branches and trunks. Then pinhead-sized orange bumps appeared in the areas near the damaged bark. Within weeks of their appearance, all the affected branches died. Merkel didnt know what was attacking his chestnut trees, but he hoped that the approaching winters cold temperatures would stop it.

Unfortunately, the mysterious blight dashed his hopes the following spring. The disease remained. Even worse, it spread. It killed American chestnut seedlings sprouting in the parks greenhouse. It infected chestnut saplings in the tree nursery outside. It attacked the enormous trunks of hundred-year-old chestnut trees. Determined to save them, Merkel cut off the infected branches. He sprayed the trunks with liquids formulated to kill tree diseases. Nothing halted the blight. One after another, the parks magnificent chestnut trees began to die.

Workers sprayed the parks chestnut trees, hoping to kill the disease that was attacking them.

Desperate for help, Merkel contacted William Murrill, a scientist at the nearby New York Botanical Garden. Perhaps Murrill would know what was killing Merkels trees. Maybe he could save them.

THE CULPRIT

Murrill couldnt help until he identified the culprit. The orange bumps that surrounded the ugly wounds gave him an important clue. He thought they looked like the reproductive parts of a fungus. Fungi are organisms that live and grow on organic matter such as plants and animals. This worried Murrill because he knew that some fungi are harmful, even deadly, to other forms of life.

To confirm his suspicions, Murrill collected material from the trees wounds and put it on a nutritious gel inside a shallow glass container called a petri dish. He covered the dish and waited. Within days, tiny white threadsthe sign of a growing fungusreached across the gel. As days passed, the fungus spread; its color changed from white to yellow. When the fungus was completely grown, it started reproducing. The reproductive parts of the fungus turned a deep orangethe same color as the tiny bumps that Merkel had found on the parks chestnut trees. Murrill had solved the first mystery: A fungus was causing the blight.

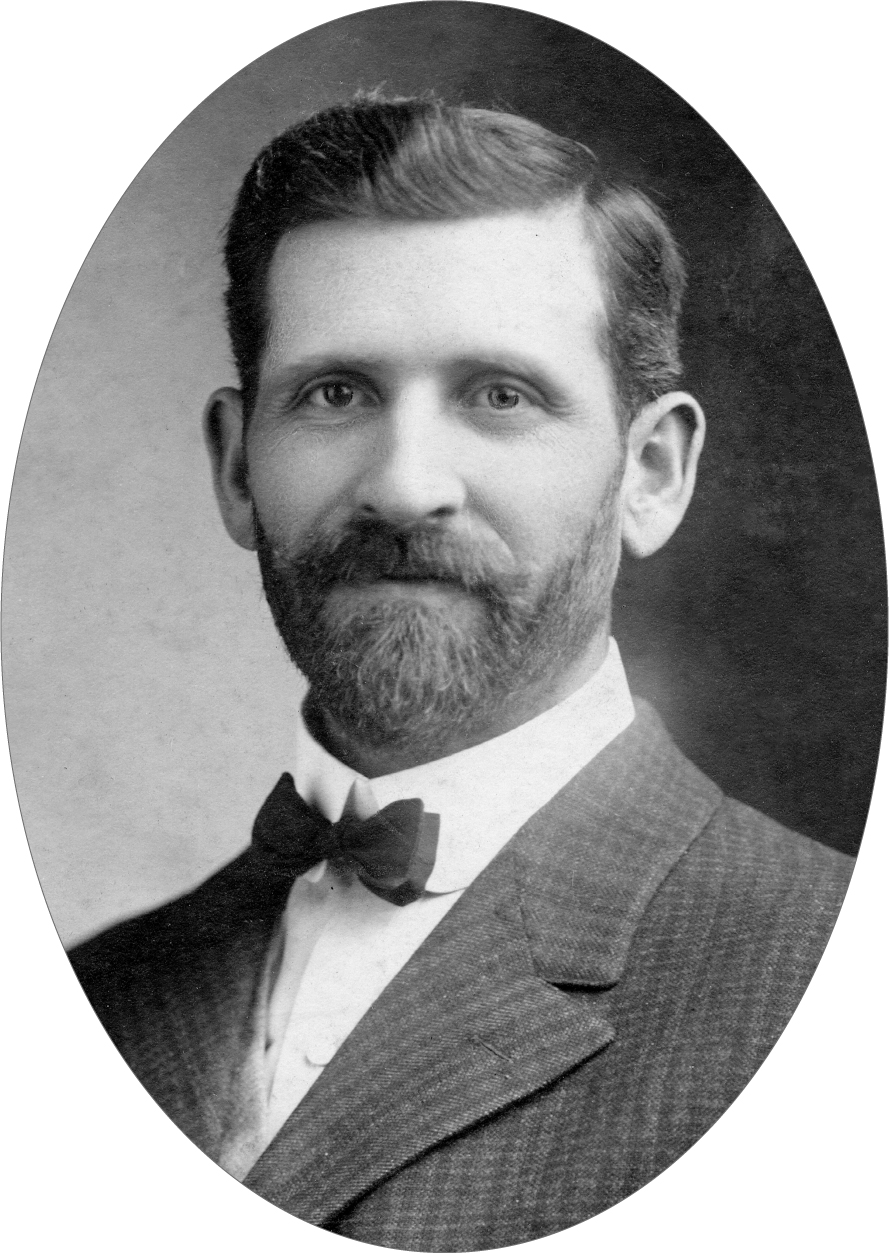

William Murrill was an expert at identifying plant diseases.

Meanwhile, more of the parks chestnut trees were getting sick. But until Murrill figured out how the fungus got inside the trees, he couldnt give Merkel advice on how to stop it. Searching for a way to fight the fungus, Murrill purposely gave the blight to some healthy young chestnut trees in his greenhouse. He smeared a small amount of the blight fungus on their bark. Several weeks passed. Nothing happened.

Puzzled, Murrill tried again. This time he scraped a hole in the trees bark and exposed the tissue beneath. Then he put the fungus directly into the small wounds. Within four to six weeks, all the branches above the wound sites were dead. That solved the second mystery: Any wound that exposed the tissue layer beneath the barka scratch from a squirrels claw, a hole gouged by a woodpecker, a break caused by the wind snapping off a branchprovided a doorway for the fungus to reach the trees inner tissue.