Tell me, pauper son, said the witch Nimiane. Before I harvest the faeren, before I rouse your father to watch his seventh son die, why did you come? You have many portals. You could flee through the worlds and live a while. Why come to your death?

Henry shifted, clenching the grip on his sword. You know why, he said. I come because of the words spoken when I received my name. I come because you are the darkness, and I am dandelion fire. You have seen me in your dreams. You know what I can do to you.

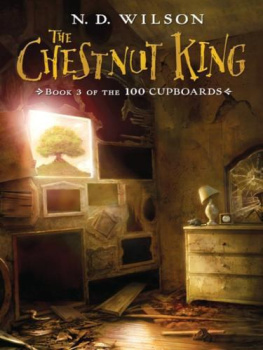

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright 2010 by N. D. Wilson

Cover art copyright 2010 by Jeff Nentrup

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House Childrens Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Random House and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The frontispiece illustration by Jeff Nentrup, copyright 2007 by Jeff Nentrup, was originally published in 100 Cupboards by N. D. Wilson.

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

PRELUDE

I n a world tangled in places with this one, both near and far from where we stand, near and far from where our grandfathers are standing as children, near and far from our past, from our now, from our never, there are two seas separated only by a long and strong belt of land. To the north, the belt widens and a continent divides the waters. To the south, another. But here, the two seas mingle in rivers and canals, in inlets and streams, in the bodies of fish and water beasts that creep through the mazes from sea to sea. Here, there is a city possessing the channels and canals, possessing the seas and the lands both north and south. Here, the streets wind like tangled veins, carrying the lives of thousands with their pulsing. Here, there are walls built on walls built on walls built on forgotten kings and wars and countries and cast-up coral bones. Streets and houses and gardens nest on the broad-backed stone and overlook the sprawling waters. Here, there are palaces and temples heaped up to kings and empresses and gods, known to the dead, forgotten by the living.

In this city, great gates open to the lands both north and south, and greater sea gates, broader and taller than five-tiered galleys, shelter harbors both east and west.

Here, in the center of this city, with rounded stone peaks and shaded fountains, one palace stands peacefully, walled within the walls, carving out silence for itself. Here, tucked beneath a palace shoulder, there hangs a towered garden.

In the garden, there sits a woman. In her arms, there sits a cat.

CHAPTER ONE

Every year , Kansas watches the world die. Civilizations of wheat grow tall and green; they grow old and golden, and then men shaped from the same earth as the crop cut those lives down. And when the grain is threshed, and the dances and festivals have come and gone, then the fields are given over to fire, and the wheat stubble ascends into the Kansas sky, and the moon swells to bursting above a blackened earth.

The fields around Henry, Kansas, had given up their gold and were charred. Some had already been tilled under, waiting for the promised life of new seed. Waiting for winter, and for spring, and another black death.

The harvest had been good. Men and women, boys and girls had found work, and Henry Days had been all hot dogs and laughter, even without Frank Williss old brown truck in the parade.

The truck was over on the edge of town, by a lonely barn decorated with new No Trespassing signs and a hole in the ground where the Willis house had been in the spring and the early summer. Late summer had now faded into fall, and the pale blue farmhouse was gone. Kansas would never forget it.

Dry grass rustled against the barn doors and stretched up the sides of the mud-colored truck. Behind the barn, in the tall rattling grass, Henry York was crouching beside the irrigation ditch. Sweat eased down his forehead from beneath the bill of his baseball hat. A long piece of grass dangled between his teeth, and a worn glove hung on his right hand.

The field across the ditch was as black as any parking lot, and the sky above him held only the smoky haze that had so recently been wheat and the late-afternoon sun, proud to have baked the world.

Henry slapped a fist into his glove, shifted in his crouch, and flashed two fingers down between his legs.

Again? Zeke Johnson asked.

Henry smiled and nodded. It was his favorite pitch to catch. He watched the tall boy wind up, arms tight, leg high, and then Zeke uncoiled, striding forward, arm extending, and the ballstring wrapped tight around a rubber core, all stitched up in leathercame spinning toward him.

Zeke was throwing hard, and Henry, crouched with his left arm behind him and his right arm stretched out, tracing the ball, had no mask, no shin guards, no chest protector, no catchers mitt. He didnt care. He didnt even notice.

People who had known Henry in Boston would have had trouble recognizing him, even though his looks hadnt changed that drastically. To Kansas, he was the same boy whod once been plucked crying out of an attic cupboard by an old man, who had returned twelve years later, fragile and afraid. But to Kansas, a tadpole is the same thing as a frog. Henry was a little taller, his shoulders were a little wider, and his jaw was scarred, but it was the boy inside the body that had really changed. And his eyes. His eyes would go the color of midnight when they really wanted to see. When he let them. When he couldnt stop them.

They were black now, following Zekes curve ball as it carved through the air. To Henrys eyes, strings of force trailed the ball, connecting with Zekes hand and fingers, straggling into his shoulder and back and hips. The air bent around the spinning ball, and pushed. In an instant, the ball shifted, as Henry knew it would. High and inside on any right-handed batter, it broke down and across the imaginary plate. With a snap, it stopped in the old leather web of Henrys glove. The forces, the threads, the crackling trails all tattered and faded, sliced and destroyed by the grass, swallowed by the world.