Lets talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs

Lets choose executors and talk of wills

For Gods sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings

William Shakespeare, Richard II, Act III, Scene II

Contents

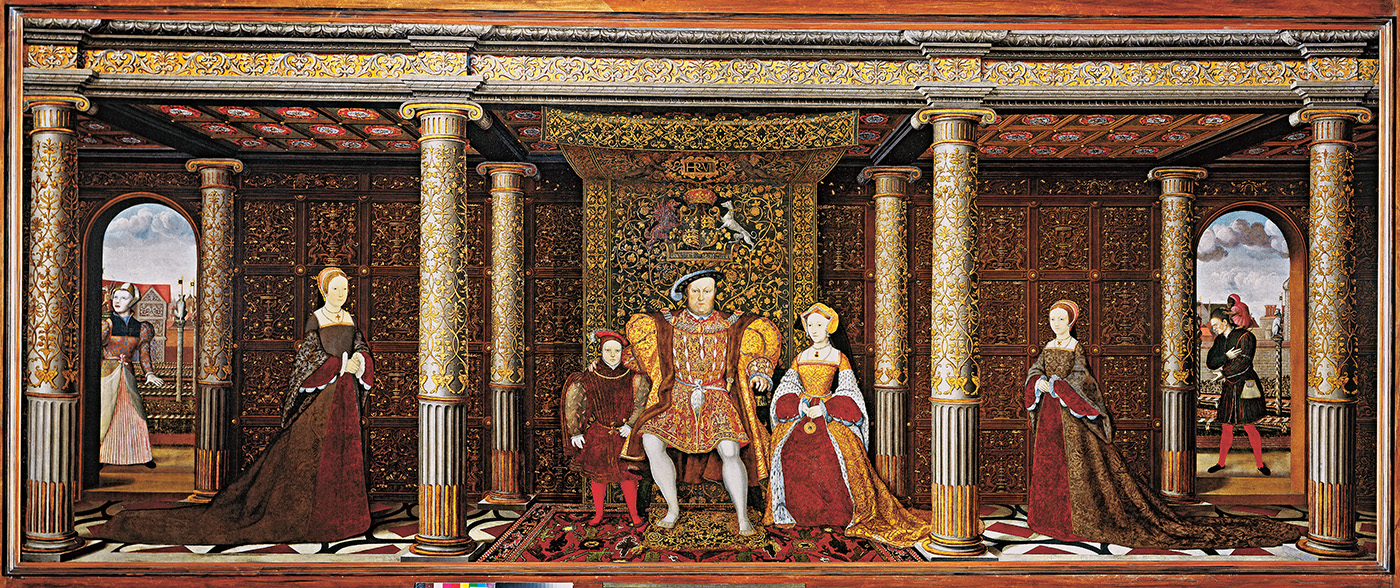

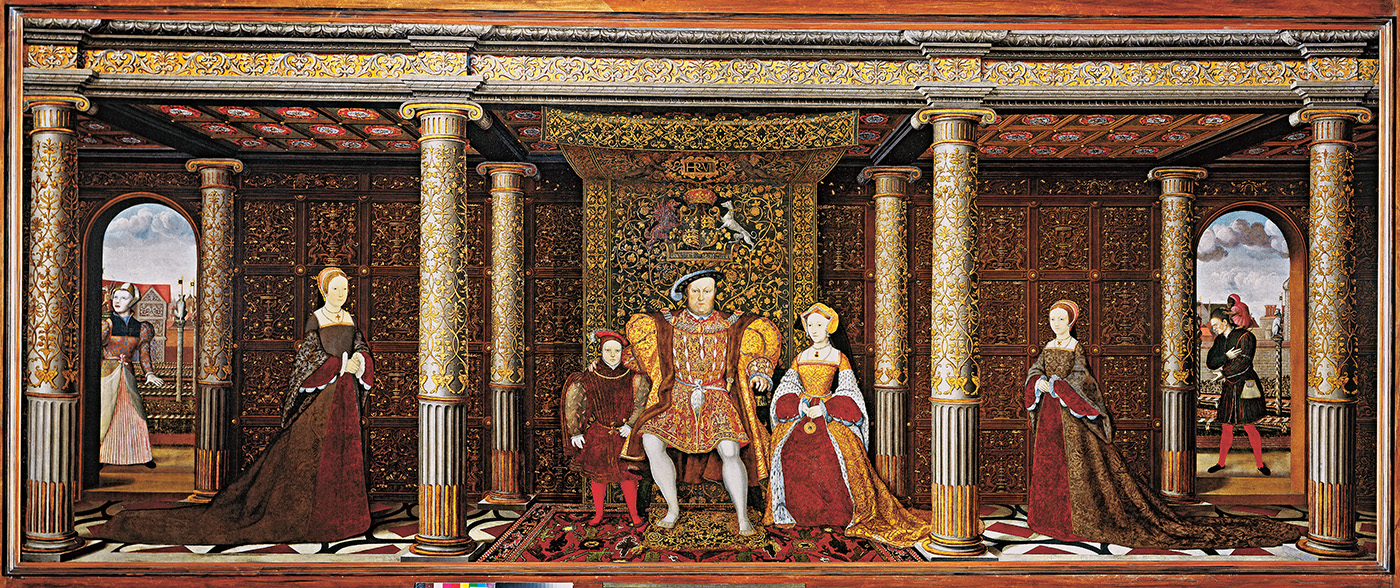

The family of Henry VIII, painted by an unknown artist. This picture, from 1545, depicts Henry VIII at Whitehall Palace with his offspring: his daughters twenty-nine-year-old Mary ( left ) and twelve-year-old Elizabeth ( right ), and, close at hand, his eight-year-old son, Edward, around whom Henry has an arm. It is an idealized image: the wife on Henrys left was not his wife in 1545 Kateryn Parr but rather his third wife, Jane Seymour, who gave him his son and heir. Curator Brett Dolman has observed that Henry, Jane and Edward appear very much as a Holy Family, adored by the two princesses. The man in the archway is Will Somer, the kings fool.

Henry VIIIs last will and testament is one of the most intriguing and contested documents in British history. Given special legal and constitutional significance by the 1536 and 1544 Acts of Succession, which allowed Henry to nominate his successor in his last will, it is exceptional among English royal wills. For Henry VIII, the monarch so renowned or notorious for remarrying in pursuit of a male heir, the succession was his abiding obsession until the very end.

Throughout the sixteenth century, Henry VIIIs will was called upon to determine the course of history. On the accession of Henrys nine-year-old son as Edward VI, Henrys will was used both to justify government by a regency council under the increasingly authoritarian sway of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, as Lord Protector of England, and then to warrant the dissolution of Somersets protectorate in October 1549. Four years later, the will was overruled if temporarily to divert the succession to Edward VIs cousin, the Protestant Lady Jane Grey. During Elizabeth Is reign, it was deemed invalid by those who supported Mary, Queen of Scots claim to the English throne.

Despite these challenges, however, until Elizabeths own death and the accession of James VI of Scotland as Englands James I in 1603, the sequence of childless English monarchs over the previous half-century meant that the line of succession as laid out in Henry VIIIs will came to pass.

In the centuries since, historians have disagreed vehemently over the wills intended meaning, its authenticity and validity, and the circumstances of its creation. One school of thought represented by such great names of Tudor history as Geoffrey R. Elton, David Starkey and John Guy has argued that it was the product of a conspiracy staged by an evangelical or proto-Protestant faction at court seeking to advance religious reform, led by Edward Seymour (at that time Earl of Hertford) and Sir William Paget. These historians assert that the will remained unsigned until Henry was on his deathbed; that, in the month between Henry drawing up its final form in December 1546 and his death on 28 January 1547, Hertford and Paget added clauses enabling their subsequent assumption of power; and that the will was hurriedly stamped as Henry lay dying, to ensure its legitimacy. Having manoeuvred to guarantee the dominance of religious reformers on the Privy Council which meant destroying the religious conservatives who stood in their way the evangelicals, it is argued, were then perfectly poised to attain control of the government at the accession of Edward VI.

In this book, I disagree wholeheartedly with this interpretation. Although faction did exist at court, I am convinced that these historians have been too influenced by the sixteenth-century martyrologist John Foxes estimation of Henry VIII: according as his counsel was about him, so was [he] led. I believe by contrast that until very close to the hour of his death, Henry was clearly directing events.

In the course of my research, I have also discovered that the case for a coup by reformers and for an alteration of the will is based on some notable errors. These are described fully in the narrative that follows, and in its Notes on the Text, but it is worth briefly mentioning here the three main bones of contention.

The first is the assertion that, as Professor Elton put it, the Privy Council for a crucial month (8 December 1546 to 4 January 1547) met not at court but in Hertfords town house and that this locus for their meetings indicates the growing power of the alleged reformist faction at that time. He was not only Henrys lord chancellor but a prominent religious conservative . This piece of evidence, used to imply the domination and manipulation of Englands primary organ of government by the reformers as they built their power base, therefore proves nothing of the sort.

More significantly, some historians claim to have, as one put it, incontrovertible evidence that the will was altered. With the dismantling of this error, the theory that the will was tampered with starts to look structurally unsound, and indeed becomes unsustainable.

Third, and finally, there is the notion that Henry VIII could not bear to think of his impending death, as first alleged by Foxe and taken up by later historians. In the face of his mortality, Henry was probably not the ostrich that has been depicted.

~

Having pointed to these specific points of interpretation, I ought to add that every historian builds on the work of others, as much as he or she questions it. Many historians have brought their excellent logic and profound analysis to bear on the questions I consider here. Their scholarship has illuminated the murky business of unravelling Henrys will, and I owe a debt of thanks to them, and to others besides, whose names appear in this books Acknowledgements. In adding one more layer to the accumulation of comment and opinion about the circumstances and meaning of Henry VIIIs last will and testament, I hope that I, too, have brought a little more light to bear.

SUZANNAH LIPSCOMB

Chteau de Foncoussires

April 2015

SDG

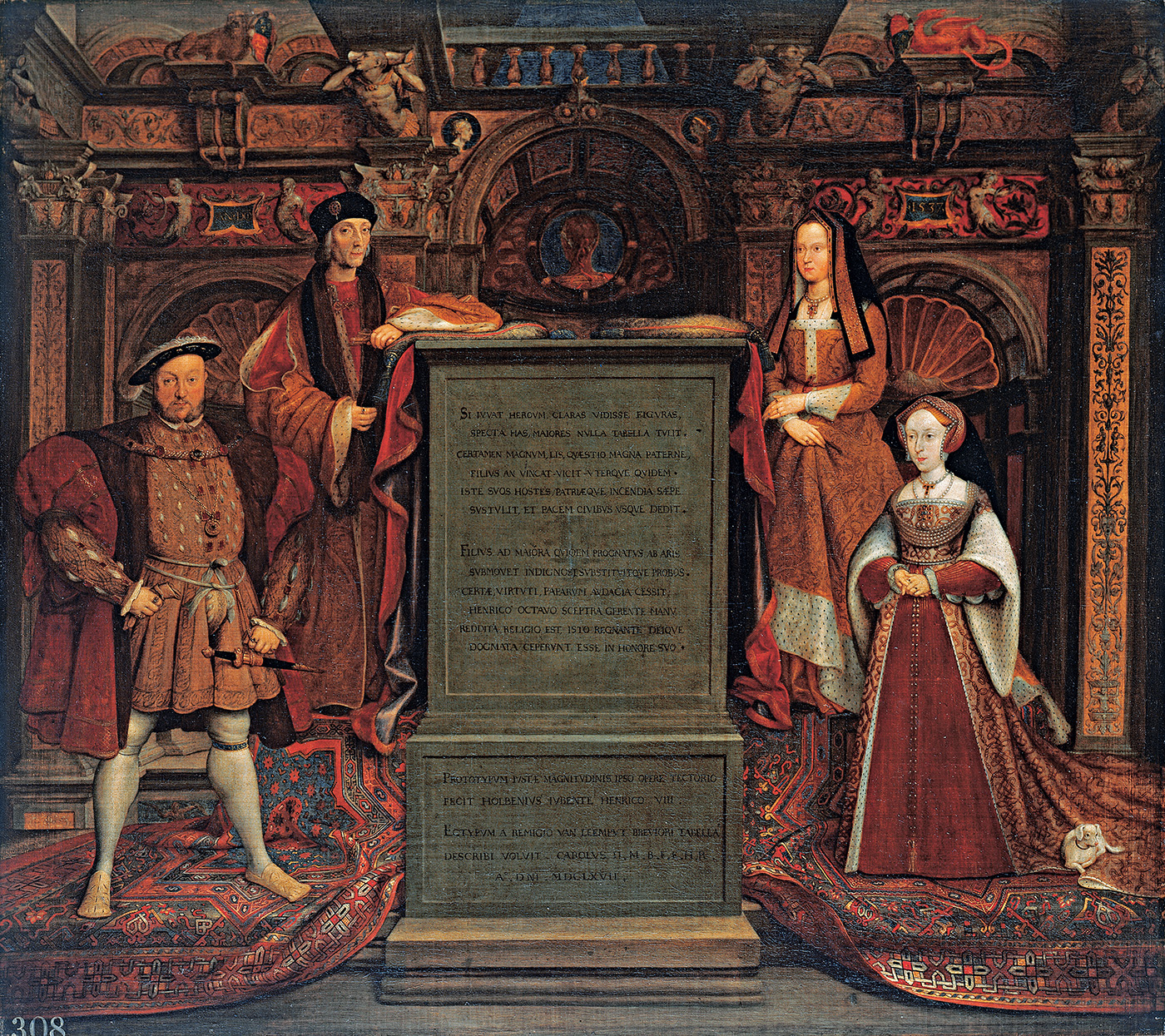

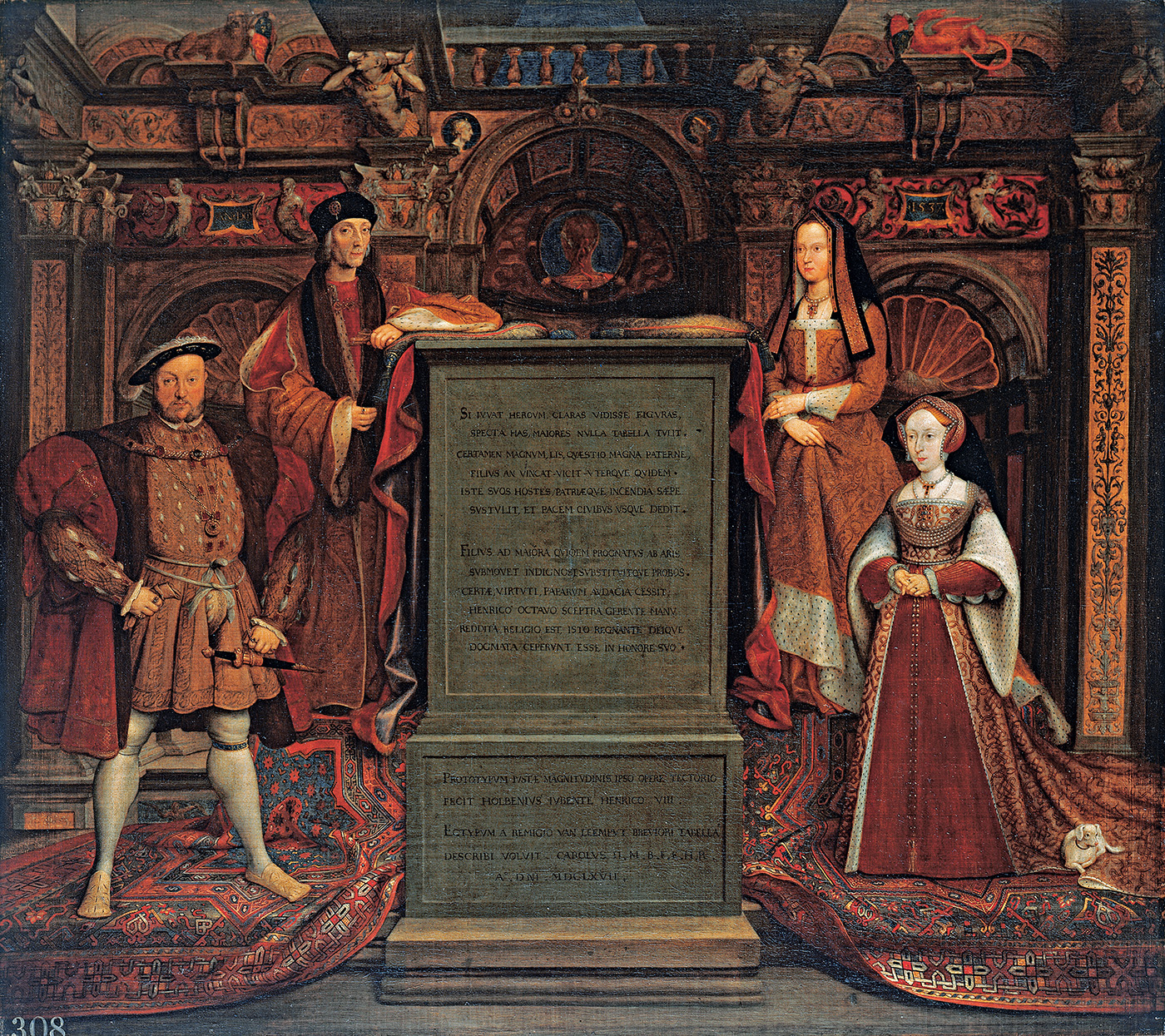

The Whitehall Mural, in a 1667 copy by Remigius van Leemput. This arrangement of Henry VIII, Jane Seymour and Henrys parents Henry VII and Elizabeth of York appeared originally, in 1537, as a 9-foot by 12-foot (2.8 x 3.6 metre) mural by Hans Holbein the Younger, at Whitehall Palace. Whitehall burnt down in 1698, but two small copies of the mural, including this one, had been made. In the depiction, the closed body language of Henrys parents and wife contrast with his confident, open stance, and Henrys huge masculine shoulders are exaggerated by his voluminous gown.

SPELLING

Although I find the curious orthography of the sixteenth century enchanting, in the main text of this book I have modernized spelling and punctuation, and silently expanded contractions, for ease of reading.

The spellings used by the authorities I cite or quote have, though, been retained in the books endnotes (Notes on the Text); and the full, unmodernized, original-spelling version of the will appears as Appendix I.