Chapter One

An Unexpected Crown

A lthough Henry VIII is perhaps Englands most famous, or notorious, monarch, he should never really have been king at all. He was born on 28 June 1491, the second son and third child of King Henry VII and his queen, Elizabeth of York. It was his older brother Arthur who, as the eldest male child, was set to inherit the crown on the death of their father.

Arthurs birth in September 1486 had been eagerly awaited and was greeted with national rejoicing and a good deal of ceremony. That the first royal child was a son who would ensure the succession was always good news, as Henry himself would discover to his cost when he became king. In this case, after all the years of unrest in England during the Wars of the Roses, it was especially important that the new Tudor dynasty should be properly established.

Three years later, in 1489, the birth of Arthurs sister Margaret was also marked with much pomp and celebration, culminating in a fine christening in Westminster. Young Henry, by contrast, came into the world with very little publicity. He was born at Greenwich Palace, down the river from Westminster and considered to be one of the kings out of town residences. Henry did not receive the kind of attention his siblings had had. His grandmother, who recorded all the important family events in her bible, barely mentions Henrys arrival, whereas the births of the two older children are recorded in great detail, down to the exact time (in the morning afore one of the clock after midnight, in Arthurs case).

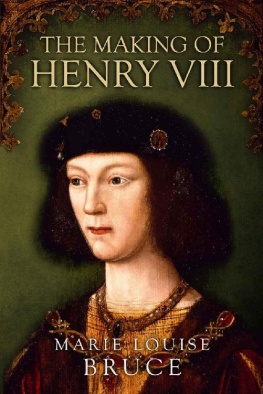

This first known picture of Henry VIII shows a sturdy toddler with a mass of curly hair that we know from other sources to have been reddish-gold. Already out of baby clothes, he wears a tunic and has a gold chain.

Greenwich Palace, built by Humphrey of Gloucester in 1447, was the principal royal palace for 200 years. Originally known as Bella Court, it was renamed the Palace of Placentia (or Pleasaunce) by Margaret of Anjou, queen to Henry VI.

However, being born the second son had its advantages. While Arthur was groomed for kingship right from the start, Henry enjoyed a more informal childhood and was allowed more freedom. He grew up with his sister Margaret in the royal nursery at Eltham, where they were soon briefly joined by three more sisters and a brother, of whom only one, Mary, survived childhood. When she came into the world in 1496, the family was still mourning the death of Elizabeth, a second daughter who had died aged three just six months before. A third son, Edmund, was born in 1499, but the little prince lived for less than eighteen months. In 1503 Queen Elizabeth gave birth to another daughter, Katherine, but this child survived for only a few days. Childbirth was a dangerous business in those days, and most families, rich and poor alike, were used to the early deaths of children. For the royal family, it was a cause of constant anxiety as well as sadness, as they were only too aware that the succession depended on the survival of healthy male children.

King Arthur

King Arthur was the fabled king of the ancient Britons who set up his court and the Round Table fellowship of knights at Camelot. The legends of King Arthur were widely known in Tudor times and many people believed him to have been real. The site of Camelot was thought to be the city of Winchester in southwest England. Henry VII, who was both superstitious and shrewd, made arrangements for his new son and heir to be born and christened in that ancient town. He also named him after King Arthur. In this way he hoped to give the new Tudor dynasty authenticity by linking it to the ancient line of British kings.

What is traditionally known as King Arthurs Round Table hangs in the Great Hall of Winchester Castle.

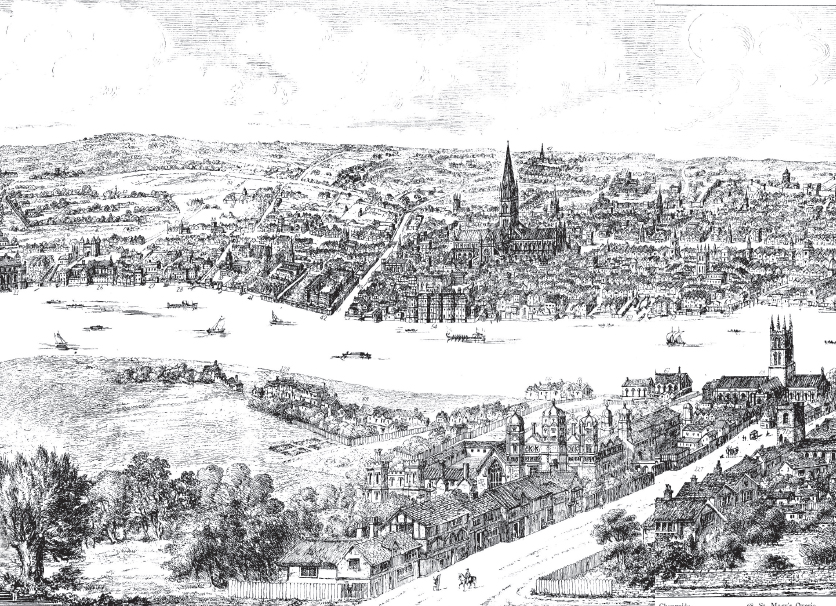

A panorama of the River Thames in 1543 reveals how buildings clustered in a strip along the north bank. The Palace of Whitehall, with its landing stage, can be seen on the left, with Westminster Abbey behind and further left. The building with a spire on the right is old St Pauls Cathedral.

Henry, therefore, spent most of his life with two sisters and in the company of his mother, who was a gentle and affectionate woman. Royal children often had a fairly distant relationship with their parents, but Queen Elizabeth is said to have taught her son to read and write, and they remained close throughout Henrys childhood. Perhaps it was growing up as the only boy in this unusually feminine environment that helped to mould Henrys later character. Not only was he clearly attractive to women, but he appears to have enjoyed and been happy in their company in a way that was unusual in the testosterone-fuelled Tudor society. On the other hand, he was undoubtedly spoiled and cosseted and became used to getting his own way.

Into the spotlight

In 1494, when he was just three years old, Henry found himself suddenly thrust into public view when his father decided to give him the title Duke of York. This was prompted by recent events, which had threatened Henry VIIs claim to the throne. A young man named Perkin Warbeck had appeared, claiming to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the two Princes in the Tower. These were the two sons of Edward IV, who were thought to have been murdered by their uncle, Richard III, so that he could claim the crown. If Perkin Warbeck could be proved to be the real prince, his claim to the throne would be much stronger than Henrys and would be a serious threat to the Tudor dynasty. Warbeck was supported by many powerful figures in the courts of Europe, particularly by Margaret, Dowager Duchess of Burgundy, Edward IVs sister and therefore the young princes aunt. King Henry needed to distract attention from all this until Warbeck could be exposed as a fake. He decided to create a real Duke of York and show him to the people in one of the greatest demonstrations of power and magnificence that England and Europe had ever seen.

Trouble in the future

The descendants of Henrys two surviving sisters were to be the cause of a good deal of trouble in later generations. His younger sister Mary was married to King Louis XII of France when she was just eighteen and he was 52. When he died, she secretly married Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, against the wishes of her brother. After Henrys death, their granddaughter, the tragic Lady Jane Grey, became Queen of England for just nine days before being executed in 1554. Henrys older sister Margaret married King James IV of Scotland and became the grandmother of Mary, Queen of Scots. Marys claim to the English throne was to prove a great threat to peace during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

Next page