I would like to thank the staff of Hampton Court Palace, especially Mr Dennis McGuinnes, Dylan Hammond, Anne Fletcher, Caroline Allington, Laura Cappellaro and Andrea Selley, together with all those who have warded and cleaned the kitchens during the Christmas events since 1991. Without their very positive assistance, it would have been impossible to have achieved such considerable success. Along with everyone interested in the history of the Tudor court, I also owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Dr David Starkey and Dr Simon Thurley, whose publications, of the highest scholarly excellence, have rendered so much primary evidence readily available for study. It should be stressed, however, that all views expressed in this book are entirely my own responsibility, having had no input from the curatorial staff of Historic Royal Palaces or elsewhere.

The practical operation of the kitchens has placed demands on all the historical interpreters who have worked here as Tudor cooks at the Christmas events. In addition to researching and making their own clothing, they have worked long days, frequently at sub-zero temperatures, chopping, pounding, turning spits, while still keeping up a constant flow of good-humoured, informative conversation with thousands of visitors. Then came the masses of washing and scouring of everything before retiring, exhausted, to their spartan garrets, just like their Tudor predecessors. For all this, and their friendship, I take the greatest pleasure in thanking the whole team: Marc Meltonville, Kane Allen, Lawrence Beckett, Andrew Butler, David Cadle, Barry Carter, Andrew Crombie, Richard Fitch, Robert Hoare, Marc Hawtree, John Hollingworth, Richard Jeale, Robin Mitchiner, Gary Smedley and Adrian Warrell.

I would also like to extend my thanks to Mr. James Doyle and the staff of the Souvenir Press for their care and attention in the editing and production of this new edition.

Peter Brears

Leeds, 2011

Contents

King Henry VIII is one of the most memorable figures in English history. His portraits still convey his indomitable power and presence, while history records his dynamic actions; marrying six wives, establishing the Church of England, leading military expeditions into Europe, and effectively creating this countrys major defences on both land and sea. He was also a builder on the most prodigious scale, constructing palaces and gardens of true magnificence. Most of these have disappeared over the last four hundred years, but much of his Hampton Court still survives intact, closely identified with King Henry in the public consciousness.

Having acquired the palace from Cardinal Wolsey in 1529, Henry rapidly expanded its accommodation and services to produce one of the most impressive residences of its day. Every detail was purposely designed to facilitate the highest degree of stately magnificence, control and efficiency. Having to provide meals and accommodation for up to 1,200 people, it elevated domestic planning to a truly industrial scale. His kitchens at Hampton Court are probably the earliest, largest, finest and best-planned of Englands innovative factories, their scale and sophistication remaining unrivalled over the next 250 years.

In 1737 the royal court left the Palace for the last time, and the kitchens were adapted for other purposes, including that of grace-and-favour residences granted by the monarch to worthy individuals. It is still remembered that one of the great kitchen fireplaces served as a bathroom for the late Lady Baden-Powell, the Chief Guide, in the earlier twentieth century, sooty drops falling down the wide chimneys on wet days! In order to satisfy a growing public interest in historic kitchens, the Department of the Environment carried out a major restoration programme in 1978, removing many of the later partition walls and inserted floors.

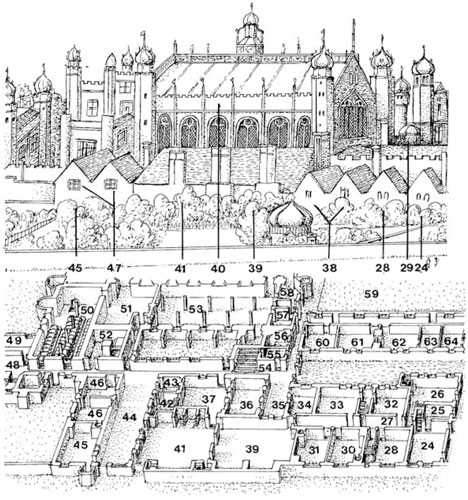

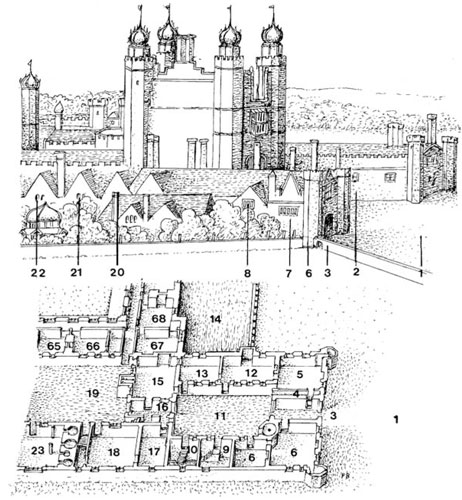

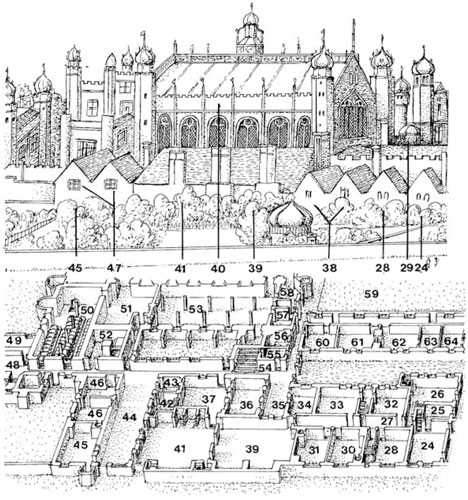

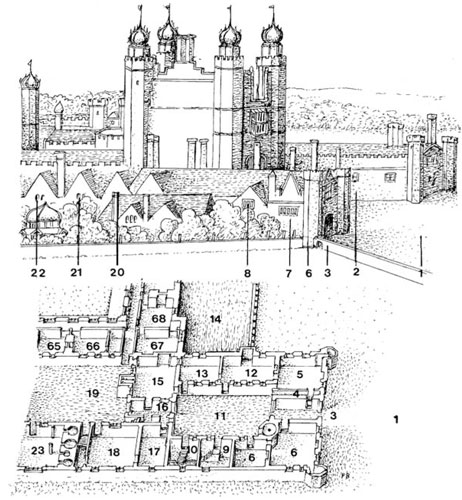

1.The Kitchens, Hampton Court Here the kitchens are seen from the north, as shown in Anthonis van der Wyngaerdes watercolour drawing of around 1558 on which the top drawing is based. The key is numbered from right to left, following the progress of the food from the Outer Court through to the Great Hall.

1.Outer Court

2.Great House of Ease (latrines)

3.Back Gate

4.Porters Lodge (?)

5.Yeoman and groom of the Counting House (?)

6.Jewel House

7,8.Comptrollers lodgings

9.Comptrollers Cellar

10.Kings Coal House

11.Greencloth Yard

12.Spicery office

13.Chandlery

14.Moat

15.Clerk comptroller

16.Inner gateway

17.Bottle House (Salt Beef Store?)

18.Dry Fish House

19.Pastry Yard

20.Scullery office

21.Pastry office

22.Confectionary

23.Pastry Bakehouse

24.Pastry workhouse

25.Pastry (Storehouse? Boulting House?)

26.Boiling House

27.Paved Passage (Fish Court)

28.Dry Larder

29.Stair from Buttery to Great hall

3031.Hall-place workhouses

32.Wet Larder

33.Larder

34.Hall-place dresser office

35.Hall-place dresser

36.Pewter Scullery

37.Scullery Yard

38.Cooks lodgings (?)

39.Hall-place kitchen

40.Great Hall

41.Lords-side kitchen

42.Lords-side dresser office

43.Silver Scullery (?)

44.The Great Space

45.Lords-side kitchen-workhouse

46.Clerk of the kitchens lodgings

47.Wafery and lodgings for surgeons and others

48.Stairs to Great Watching Chamber

49.Drinking House

50.Great Wine Cellar

51.Privy Wine Cellar

52.Stairs to Great Watching Chamber

53.Beer Cellar

54.Stairs to Great Hall

55.Almonry

56.Bread delivery room

57.Privy Buttery

58.Great Buttery

59.Base Court

6068.Lodgings

In 1990 Dr Simon Thurley, first Curator of the Historic Royal Palaces agency, published the architectural history of Henry VIIIs kitchens at Hampton Court, and re-displayed them with a variety of original and reproduction artefacts and an introductory exhibition. This proved extremely popular with all visitors, now attracting them in increasing numbers. It was at this point that Historic Royal Palaces, knowing my work in the restoration and operation of historic kitchens, asked me to introduce the first live re-enactment in any of the royal palaces. The aim was to show the kitchens in action, with accurately researched and reproduced utensils, clothing, cooking methods and ingredients as used here in the 1530s and 40s. This presented a real challenge, for there were only a few weeks in which to make the necessary preparations. These included recipe research, the sourcing of foodstuffs, practical equipment, furniture and period-style clothing, detailed negotiations regarding housekeeping, conservation, public safety and security matters, and the logistics of transport, accommodation and staffing. All was to be ready by 9a.m. on 27th December, 1991, when the royal press corps, numerous other reporters and the first of thousands of visitors expected to see the kitchens in full action for the first time since 1737.

Together with my colleagues Marc Meltonville, Gary Smedley and Adrian Worrell, I arrived at the Palace late on the previous evening to take up residence in the original confectioners quarters. Next morning we were given our first access to the kitchen just after 8a.m., with under an hour to clad the early stoves with firebrick and sheet metal, set up the work-tables with all their equipment, carry in the logs, charcoal, water and food and put everything in place. In the middle of all this the butcher arrived with the roasting joint for that day, a huge pig, over five feet from snout to rump, which had to be mounted on the Palaces slender spits. Work on this had hardly started when the press rushed in, dozens of reporters and photographers representing newspapers, magazines and agencies, along with several national and regional television and radio crews. They all gave excellent coverage for the event, ensuring its success. Over the next few days tens of thousands of visitors passed through the kitchens, many being international tourists spending Christmas in London, along with others from the Home Counties.

Next page