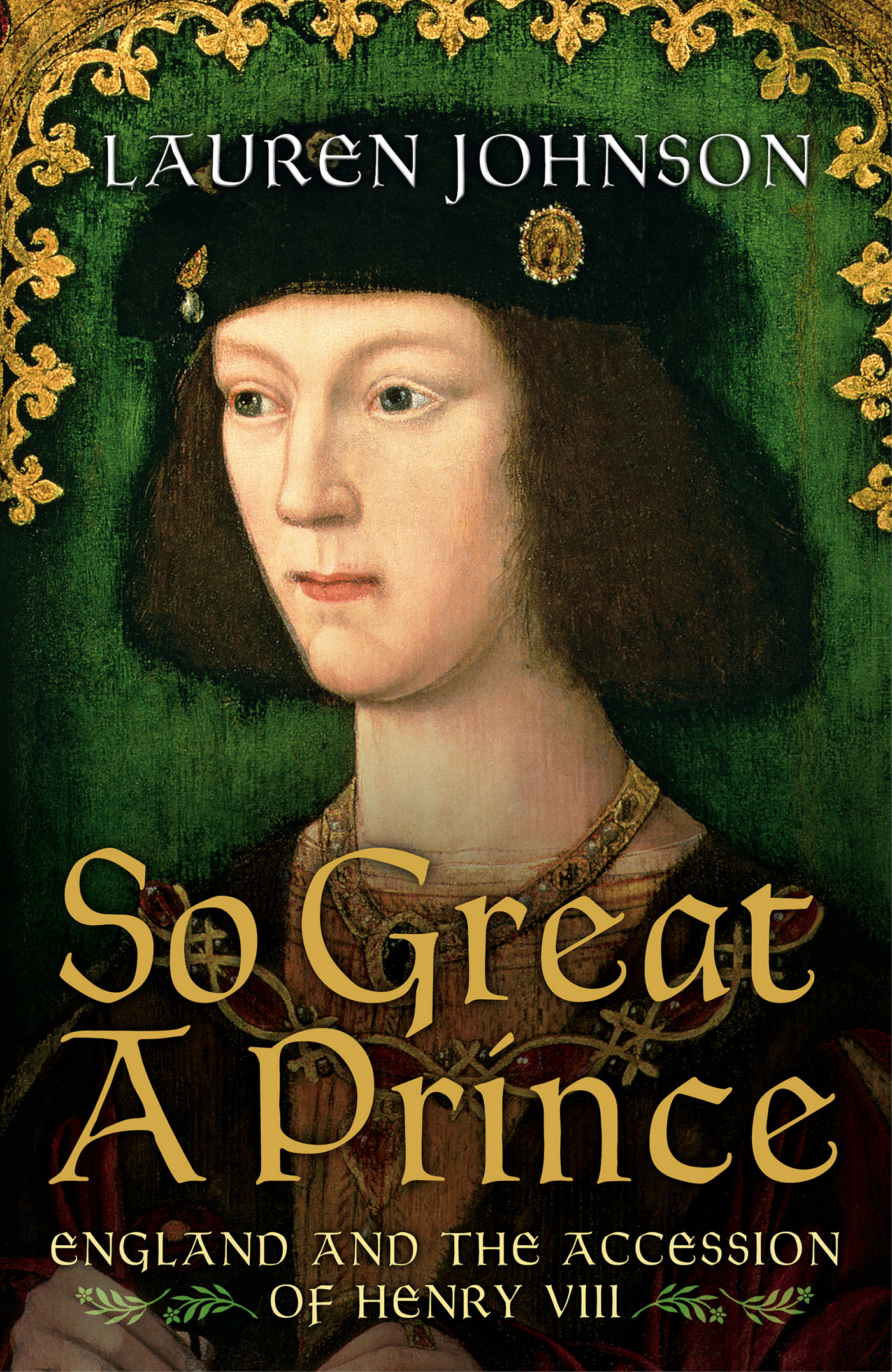

Lauren Johnson

So Great a Prince

www.headofzeus.com

E NGLAND , 1509.

Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch, is dead; his successor, the seventeen-year-old Henry VIII, offers hope of renewal and reconciliation after the corruption and repression of the last years of his fathers reign.

The kingdom Henry inherits is not the familiar Tudor England of Protestantism and playwrights. Two decades and more before the English Reformation, ancient traditions persist: boy bishops, pilgrimage, Corpus Christi pageants, the jewel-decked shrine at Canterbury. So Great a Prince offers a fascinating portrait of a country at a crossroads between two great monarchs and between the worlds of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Lauren Johnson tells the story of 1509 not just from the perspective of king and court, but of merchant and ploughman; apprentice and laundress; husbandman and foreign worker. She looks at these early Tudor lives through the rhythms of the ritual year, juxtaposing political events in Westminster and the palaces of southeast England with the liturgical and agricultural events that punctuated the lives of the ordinary people of England.

CONTENTS

Time to pay your debts

To everything a time and place

An education

Youth must have some dalliance

All England is in ecstasies

Good and bad lordship

We are but dust, and die we must

Feast and Fast

Fear God, honour the king

Contrition and suspicion

Conception

Fortunes wheel

The rose both white and red, in one rose now doth grow

I N 1509 K ING Henry VII died and his son succeeded to the throne of England as Henry VIII. Behind that simple fact lies a complex story of ruthless political manoeuvring, greed and deception. For 1509 stands at a crossroads between two very different kings, and between equally different worlds. It is a point in time we think we recognize, sitting in the long sixteenth century of the Tudor age, with its Protestants, playwrights and printing presses. It seems comfortably settled between the bloodshed and chaos of the Wars of the Roses, and the bloated tyranny of Henry VIIIs later reign. From a modern vantage point we know that the Tudor dynasty would last another hundred years.

But we forget. This is not quite the Tudor world we imagine. To the men and women living in 1509 the future would not have seemed so certain. Civil war was still a visceral memory for many and the old rivals of Henry VII and the Lancastrian line exiled, deprived or imprisoned Yorkist claimants like Thomas Grey, marquess of Dorset, and Edmund de la Pole were still very much alive. Tudor rule was associated not with harmony and plenty, but with oppressive interference, thanks to the kings micromanagement and the avarice of his chief councillors, Edmund Dudley and Sir Richard Empson. Monarchical meddling in guild business, city privileges and noble freedoms meant there was not a corner of English or Welsh life that seemed free from the kings oppressive attention. Disgruntlement was rife and the notion of a country united around the Tudor dynasty looked increasingly hollow.

According to his own frequently repeated rhetoric, Henry VII had swept to power by divine sanction, winning his crown on the battlefield. This Lancastrian had married a princess of the House of York, thus restoring peace to a land shattered by civil war. Henry fervently promoted the image of the Tudor rose, coupling the well-known white rose of York with the rather less commonly used symbol of Lancaster, the red rose. In the prince and princesses who survived to adulthood Margaret, Henry and Mary this Tudor rose was made flesh. But for fifteen years the next in line to the throne, the eldest rose, had been Prince Arthur, who in 1509 lay entombed in Worcester Cathedral. His magni-ficent chantry chapel, covered with symbols of his own dynasty and those of his foreign bride, Catherine of Aragon, stood as an embodiment of the countrys uncertain future. Now his seventeen-year-old brother Prince Henry stood to inherit, an adolescent who had spent most of his childhood in the company of his sisters, his mother, his grandmother and their women. Since being removed to the company of men, he had still been kept like a girl, always under his fathers watchful eye, forbidden to join in fully with the dangerous martial pursuits of his peers. But now all of the hopes of the Tudor line fell on his broad shoulders. The precedent of the past century was not good for the young Prince Henry. The last adult prince to inherit the throne peacefully on the death of his father had been Henry V in 1413, and between that time and this lay a century of bloodshed, minority rule and usurpation.

The world seemed no more secure for the kings subjects. Beyond courts and manors the world of the labouring class was also in flux. The effects of the Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century still lingered, not only in the sporadic outbreaks of sickness that continued to ravage the country in new and horrifying forms, but in the diminished population and the resulting increase in the bargaining power of labourers. Common men and women felt emboldened, turning to the courts to appeal against unjust lordship. Serfdom, the ancient English form of slavery, had virtually disappeared. All the same, the vast majority of the kings subjects who made their living from the land had little cause for celebration. The enclosure of fields to create parkland or to feed sheep was an acknowledged problem, for while it lined the pockets of lords it caused waste, depopulation and unrest among the poor. Famine was an ever-present danger. One bad summer, one poor harvest, and scarcity could lead to starvation.

Under such circumstances, for most of the population, the accession of a new king meant little. The rhythms and rituals of daily life went on unchanged. Only in the immediate vicinity of London, or for those who had had dealings with chief royal ministers, was the change visible. For the largest part of the population the only alteration would have been the addition of a letter j to the end of the name of their king instead of Henry vii, now it was Henry viij. The face of the monarch was unknown, and since Henry VIII did not change the face on Englands silver coinage until sixteen years into his reign, the only royal likeness most of the population knew was the profile of his father. Even when Henry went on progress in the summer of 1509, to display himself to his new subjects, he stuck snugly to the Home Counties.

The early years of Henry VIIIs reign have been overlooked by many historians, who prefer to leap from the bloodshed of the Wars of the Roses to the religious and cultural upheaval of the English Reformation, when there is the added spectacle of Henrys tangled love life to consider. But we ignore this period at our peril. How can we make sense of Henrys almost pathological desperation to sire a legitimate male heir which famously led to six queens occupying the consorts throne beside him if we do not understand the precarious circumstances of Henrys own accession? How can we comprehend the impact of the Reformation if we do not first appreciate the vibrancy of the all-encompassing Catholic ritual that it shattered?

Henry VIIIs reign is probably the most tumultuous and transformative in English history. When he came to the throne, the country was Catholic, part of the universal church of Rome. By the time Henrys son Edward succeeded him, England had cut itself adrift. Henry VIII had made himself supreme head of the church in England, allowing no pope to serve as intermediary between himself and God. In 1509, translating the Bible into English was heresy, a crime against God. By 1547, when Henry VIII died, there was an English Bible in every church by royal command. Although not yet a Protestant nation, in 1547 England had cut itself off from much of the ritual and tradition of Catholicism. This was no small change. The entire structure of the year had been founded on a shared concept of religion: days to fast, days to feast, days to celebrate, days to work, days to have sex, days to abstain. Even the hours of the day were based on the liturgy of masses and prayers, and tolled by church bells. In 1509 we see, almost frozen in time, the high point of a world that would be destroyed within half a century. Looking back on it through twenty-first-century eyes, this world appears to be teetering on a precipice, but to those living through it, 1509 was a time of hope, the moment of release from a rule that had become increasingly tyrannical.