Contents

HENRY VIII

History in an Hour

Simon Court

The life of Henry VIII was extraordinarily rich and eventful, starting with high hopes but ending, as he himself would have seen it, in abject personal and therefore political failure, with the premature death of his only son and heir, Edward VI. We have been invited to view Henrys life and personality as, in effect, a tragic game of two halves: the first starring the idealistic, athletic and virtuous prince; the second embarrassed by the bloated, disillusioned tyrant who had been corrupted by events which were largely outside his control. And though it may be expected that his personality therefore fundamentally altered for the worse, it is evident that the characteristics which comprised this complex, yet essentially coherent, man were present throughout his life, and the decisions he made. For, possibly more than any other English monarch before or after him, Henry VIII defined every aspect of political life during his reign: indeed we can say that his personality became political policy.

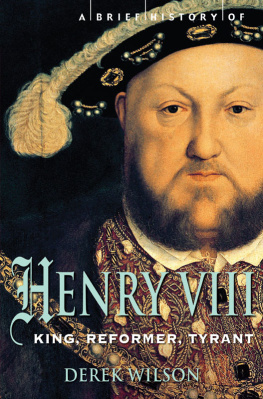

Henry was, to all outward appearances and certainly as portrayed by the court artist Hans Holbein, the perfect model of a successful king. Tall, well built and intelligent, he commanded the stage of his court.

Yet who was the real man those portraits depict, with his fleshy yet mean-lipped face? We will trace the diplomatic ambitions of the young prince, inspired by the Arthurian myth of the English monarch and his empire, and desiring to emulate the military triumphs of Henry V to become King of France as well as England; and the consequences of his continued failure to produce a legitimate male heir, leading eventually to the permanent break with Rome and the Roman Catholic faith. We will also see how his underlying insecurity led to an excessive attachment to his advisers who, once rejected, were brutally abandoned and often beheaded for their betrayals (whether real or imagined). We shall discover a man whose violence, self-righteousness and ruthlessness were certainly consistent with a severe egoist, and perhaps even some have suggested with a psychopath.

Prince Henry was never meant to be king. Born on 28 June 1491 at Greenwich Palace, he was the second son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, the first son being Arthur, Prince of Wales. Henry received a first-rate classical and theological education from private tutors, and became fluent in Latin and French. He was also taught to play a number of musical instruments and later composed music (although the long-held belief that he wrote Green Sleeves is probably false). In 1501, Arthur, aged 15, was married to Catherine of Aragon, almost 16 years old, the youngest surviving child of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile. But disaster struck within a year when Arthur, who was not of robust health, died of pneumonia. Their marriage was probably never consummated.

This tragedy propelled the young Henry, who was only 10 years old, firmly into the spotlight, as the sole male heir to the Tudor dynasty. His father protected him from performing many duties or making public appearances, and he must have been relieved when his second son grew into a fit, athletic young man, standing head and shoulders above his contemporaries. Henry became a skilled horseman, jouster, tennis player and dancer, and possessed great skill in archery and hurling the javelin. By 1508 he was to be seen at Richmond practising tilting for many hours.

Henry VII died on 21 April 1509, and the young Henry, aged 17, became king. In deference to his parents wishes, he immediately announced that he would marry Catherine of Aragon and, in spite of their six-year age difference, they initially made a happy couple. Catherine conceived within a few weeks of their marriage but, in what proved to be an ominous portent, she was delivered of a stillborn girl. Within four months, however, Catherine had conceived again, this time giving birth on New Years Day 1511 to a boy, named Henry.

The nation rejoiced at the news, and the king celebrated by jousting under the name of Coeur Loyale (loyal heart) and laying his trophies at his ladys feet, as befitting a gallant knight.

Catherine of Aragon watching Henry VIII of England joust, College of Arms, early sixteenth century

Yet tragedy struck again seven weeks later when the baby Henry died. Catherine, a devout Catholic, retreated into her devotions; Henry, after a bout of self-doubt and self-pity, turned his energies towards war against France. He knew that the best way for a young ruler to establish his international power and prestige was through warfare, so it was natural for him to pick on one of the two traditional enemies of the English, namely the Scots or the French. But behind this public foreign policy lay a set of deeply held personal beliefs about what it was to be a ruler of men.

Henrys love of jousting was not just the enjoyment of the sport; it was an expression of his fundamental belief in the moral virtues of chivalry as personified in the medieval knight. Henry was steeped in the chivalric tradition, believing that it was the duty of every nobleman to display prowess in the joust. Jousting evolved from the practices of medieval battle, where ransoms were sought, and serious injuries inflicted, but by the fifteenth century this had become the tournament in which knights competed for honour and the favour of a lady.

These combats were governed by the strictest rules of engagement and often involved artificial castles, ships or woodland grottos. The nuptials of Arthur and Catherine had been celebrated with such a tournament, and the young Henry had lapped it all up, wishing, like all gentlemen, to excel in the joust. Henry first joined in a tournament incognito in 1510 and he was soon participating regularly, most notably at Westminster in February 1511 to celebrate the birth of his son.

Henry believed that a king must be both a soldier and a man of learning. In promoting these two aspects of kingship soldier and scholar Henry was deliberately establishing a different type of identity for a king. His task was made easier by his remarkably varied skills and youthful energy. In addition to his linguistic skills he also had a good knowledge of the Bible, and was a student of mathematics, astronomy, geometry and cartography, and a talented musician with a strong singing voice. When he went on a progress in 1510, he occupied himself in shooting, singing, dancing, wrestling, casting of the bar, playing at the recorders, flute and virginals jousts and tourneys. The king was depicting himself to his people as a perfect example of the dashing Renaissance prince, and they adored him for it.

How does Henrys view of himself as ruler determine the public foreign policy of his war against France? He was fully aware of the previous triumphs of English monarchs during the Hundred Years War and their domination of large parts of France during that period. His personal hero was Henry V, and he yearned to recreate the glory of the Battle of Agincourt when, on 25 October 1415 Saint Crispins Day King Harry and his troops killed up to 10,000 French, yet lost only about 110 of their own men. The English claim to the Crown of France had been dormant since 1453, but it had never been renounced and Henry sought to bring it back to English hands.

The opportunity to do so arrived early in his reign. The French were occupying parts of (what is now) Italy and Pope Julius II was trying to put together an alliance to drive them out. When King Ferdinand II of Castile joined forces with him in October 1511 to form the Holy League, Henry jumped at the chance to join it and during the following spring a joint Anglo-Spanish attack was made on Aquitaine with the intention of recovering it for England. The attempt was unsuccessful, but the Pope announced that King Louis XII should be stripped of his kingdom of France and of the title most Christian king, conferring both on Henry instead. Anticipating a coronation by the Pope himself in Paris, Henry sought to convert this papal pronouncement into concrete political reality.