Copyright Paul Gerard OHara, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purpose of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Cover image: Toronto skyline: shutterstock.com/Naniti; background texture: shutterstock.com/donatas1205; trail and trees: istock.com/MarinaMariya. Based on a concept by Paul OHara.

Printer: Friesens

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

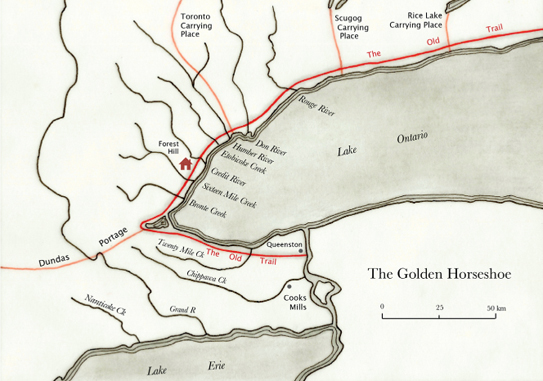

Title: A trail called home : tree stories from the Golden Horseshoe / Paul OHara.

Names: OHara, Paul, author.

Description: Includes bibliographic references.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190060387 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190060417 | ISBN 9781459744790 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781459744806 (PDF) | ISBN 9781459744813 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: TreesOntarioGolden Horseshoe. | LCSH: Human ecologyOntarioGolden Horseshoe. Classification: LCC QK203.O5 O33 2019 | DDC 582.1609713/5dc23

1 2 3 4 5 23 22 21 20 19

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country, and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Ontario, through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and Ontario Creates, and the Government of Canada.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. Lan dernier, le Conseil a investi 153 millions de dollars pour mettre de lart dans la vie des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

The publisher is not responsible for websites or their content unless they are owned by the publisher.

Printed and bound in Canada.

VISIT US AT

dundurn.com

dundurn.com

@dundurnpress

@dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

Dundurn

3 Church Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5E 1M2

For Mom

thanks for keeping me close to the trail.

One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

The problem comes when professionalism overwhelms intuitive vigour.

John Ralston Saul, The Unconscious Civilization

Contents

Preface

I park my truck by the woods at the side of the road and get my field gear together. These days I dress in white painter pants and a white long-sleeved shirt so I can see the damned ticks. Ten, twenty years ago I could romp through the woods of the Golden Horseshoe without a care. Now, ticks are something you need to be wary of because one bite can make you sick or even kill you. I douse myself in DEET from the waist down to help keep the little low-lying buggers from latching on. From the waist up, to keep the skitters at bay, I spray on a homemade mixture of water, white vinegar, and essential oils.

I slip on my rubber boots and grab my orange safety vest to check the pockets are rightly packed for the botanical inventory Im about to do: fully charged smartphone; GPS and extra batteries; clear 15-centimetre ruler; magnifying loupe; flagging tape; and a copy of Newcombs Wildflower Guide in my chest pocket. In my small backpack, I keep water, a compass, Ziploc baggies for plant samples, and an extra reference book (it could be on sedges, grasses, asters, goldenrods, or ferns, depending upon the season).

Before starting out, I sprinkle a bit of tobacco by the edge of the forest. I learned about the offering of tobacco from my friends at the Mississauga of the New Credit First Nation. It feels good to do it, to pray to the land for a good outing and a safe return.

I start off down the skid trail into the fifty-acre forested tract in the Golden Horseshoe near Lake Erie. Im usually a little nervous when I make those first steps into the woods, like theres a psychological residue of the city that I need to shake off before I can tune in to the beat of the land. But after an hour or so I start to shift down. My mind starts to calm. My heart rate slows. The mosquitoes, which buzz around and bite me for the first hour, have a harder time homing in on me as I start to blend into the green. I feel alert, yet at peace. At these times, I dont think of money, bills, relationships, time, or death. I just am, in the present, in the woods.

The flowers of an American chestnut, a tree species now listed as Endangered in Ontario.

Most of us know that feeling when walking in a forest. Its that same feeling you can get while camping or being at a cottage sipping a coffee by a lake at dawn or staring into a campfire at dusk. In the city, we can feel snatches of it in city parks or backyard gardens. The waving leaves. The birdsong. Eyes closed, feeling the sun on your face.

Its the natural frequency of humanity, of life. Its our natural idyll.

The First Nations of the Greater Golden Horseshoe the Anishinaabeg, Huron-Wendat, and Haudenosaunee built a whole philosophy, ceremony, culture, and attitude around that feeling of balance and communion with the land, in a time when all the land in the Golden Horseshoe was in a natural state, and they were immersed in it. Today, that communion with nature is increasingly hard to find.

dundurn.com

dundurn.com @dundurnpress

@dundurnpress dundurnpress

dundurnpress dundurnpress

dundurnpress