First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2017

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

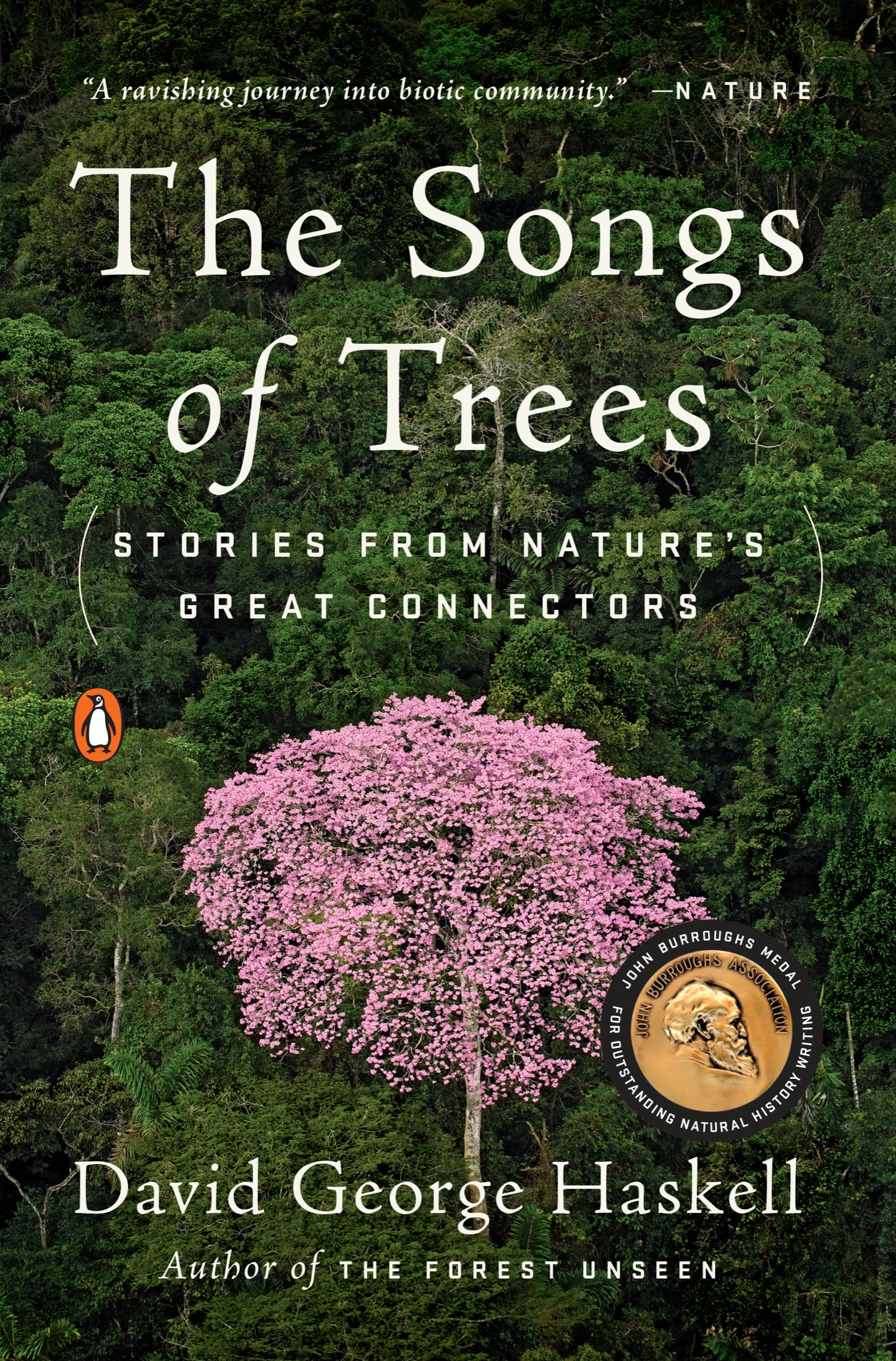

Cover photograph of young, pink leaves of Lecythis pisonis, Monkey Pot Tree, in Yasun Biosphere Reserve, Ecuador. Pete Oxford / Minden Pictures / Getty Images

Preface

F or the Homeric Greeks, kleos, fame, was made of song. Vibrations in air contained the measure and memory of a persons life.

To listen was therefore to learn what endures.

I turned my ear to trees, seeking ecological kleos. I found no heroes, no individuals around whom history pivots. Instead, living memories of trees, manifest in their songs, tell of lifes community, a net of relations. We humans belong within this conversation, as blood kin and incarnate members.

To listen is therefore to hear our voices and those of our family.

Each chapter of this book attends to the song of a particular tree: the physicality of sound, the stories that brought sound into being, and our own bodily, emotional, and intellectual responses. Much of this song dwells under the acoustic surface.

To listen is therefore to touch a stethoscope to the skin of a landscape, to hear what stirs below.

I sought trees in places whose natures seemed quite different. The first chapters of the book comprise stories of trees that seem to live apart from humans. Yet these trees lives and ours, past and future, are twined. Some of these connections are as ancient as life itself; others are industrial reimaginings of older themes. I then turn to the exhumed remains of trees that have been long dead: fossils and charcoal. These ancients show the arc of biological and geologic stories and attest, perhaps, to the future. The third group of chapters concerns trees that live in cities and fields. Humans appear to dominate; nature seems absent or in abeyance. Yet wild biological relationships permeate every being.

In all these places, tree songs emerge from relationship. Although tree trunks seemingly stand as detached individuals, their lives subvert this atomistic view. Were alltrees, humans, insects, birds, bacteriapluralities. Life is embodied network. These living networks are not places of omnibenevolent Oneness. Instead, they are where ecological and evolutionary tensions between cooperation and conflict are negotiated and resolved. These struggles often result not in the evolution of stronger, more disconnected selves but in the dissolution of the self into relationship.

Because life is network, there is no nature or environment, separate and apart from humans. We are part of the community of life, composed of relationships with others, so the human/nature duality that lives near the heart of many philosophies is, from a biological perspective, illusory. We are not, in the words of the folk hymn, wayfaring strangers traveling through this world. Nor are we the estranged creatures of Wordsworths lyrical ballads, fallen out of Nature into a stagnant pool of artifice where we misshape the beauteous forms of things. Our bodies and minds, our Science and Art, are as natural and wild as they ever were.

We cannot step outside lifes songs. This music made us; it is our nature.

Our ethic must therefore be one of belonging, an imperative made all the more urgent by the many ways that human actions are fraying, rewiring, and severing biological networks worldwide. To listen to trees, natures great connectors, is therefore to learn how to inhabit the relationships that give life its source, substance, and beauty.

Part 1

Ceibo

Near the Tiputini River, Ecuador

038'10.2" S, 7608'39.5" W

M oss has taken flight, lifting itself on wings so thin that light barely notices as it passes through. The sun leaves not a color but a suggestion. Leaflets spread and the moss plants soar on long strands. A fibrous anchor tethers each flier to the swarm of fungi and algae that coats every tree branch. Unlike their crouched and bowed relatives in the rest of the world, these mosses live where water has no skin, no boundary. Here the air is water. Mosses grow like filamentous seaweeds in an open ocean.

The forest presses its mouth to every creature and exhales. We draw the breath: hot; odorous; almost mammalian, seeming to flow directly from the forests blood to our lungs. Animate, intimate, suffocating. At noon the mosses are in flight, but we humans are supine, curled in the fecund belly of lifes modern zenith. Were near the center of the Yasun Biosphere Reserve in western Ecuador. Around us grows sixteen thousand square kilometers of Amazonian forest in a national park, an ethnic reserve, and a buffer zone, connected across the Colombian and Peruvian borders to more forest that, seen through the lofty gaze of satellites, forms one of the largest green spots on the face of the Earth.

Rain. Every few hours, rain, speaking a language unique to this forest. Amazonian rain differs not just in the volume of what it has to tellthree and a half meters dropped every year, six times gray Londons countbut in its vocabulary and syntax. Invisible spores and plant chemicals mist the air above the forest canopy. These aerosols are the seeds onto which water vapor coalesces, then swells. Every teaspoon of air here has a thousand or more of these particles, a haze ten times less dense than air away from the Amazon. Wherever people aggregate in significant numbers, we loose to the sky billions of particles from engines and chimneys. Like birds in a dust bath, the vigorous flapping of our industrial lives raises a fog. Each fleck of pollution, dusty mote of soil, or spore from a woodland is a potential raindrop. The Amazon forest is vast, and over much of its extent the air is mostly a product of the forest, not the activities of industrious birds. Winds sometimes bring pulses of dust from Africa or smog from a city, but mostly the Amazon speaks its own tongue. With fewer seeds and abundant water vapor, raindrops bloat to exceptional sizes. The rain falls in big syllables, phonemes unlike the clipped rain speech of most other landmasses.

We hear the rain not through silent falling water but in the many translations delivered by objects that the rain encounters. Like any language, especially one with so much to pour out and so many waiting interpreters, the skys linguistic foundations are expressed in an exuberance of form: downpours turn tin roofs into sheets of screaming vibration; rain smatters onto the wings of hundreds of bats, each drop shattering, then falling into the river below the bats skimming flight; heavy-misted clouds sag into treetops and dampen leaves without a drop falling, their touch producing the sound of an inked brush on a page.